The following piece is the first of two accounts in English of travels to Cambodia and Angkor Wat before the French protectorate was established, and pre-dating Henri Mouhot‘s visit of 1860. Mouhot’s posthumous ‘Voyage dans les royaumes de Siam, de Cambodge, de Laos‘, when published in 1863, popularized the ancient ruins with detailed descriptions and illustrations.

The identity of the author cannot be fully established. The following letter to the Royal Geographical Society of London is signed D. O. King. Several books on the history of Cambodia reference, or quote small parts of the letter and give the source as a David Olyphant King.

The Olyphant family (including a David Olyphant– 1789-1851) and the King family (a Dr. David King- 1774-1836, and David King Jr- 1812-1882) were both notable characters in Newport, Rhode Island during the 19th century, and the families had strong missionary and business links to China.

Cover image: Facade of Angkor Wat, by Henri Mouhot

Travels in Siam and Cambodia. By D. O. King, Esq.

June 27, 1859.

To the Secretary of the Royal Geographical Society of London.

Newport, Rhode Island, February 7th, 1859.

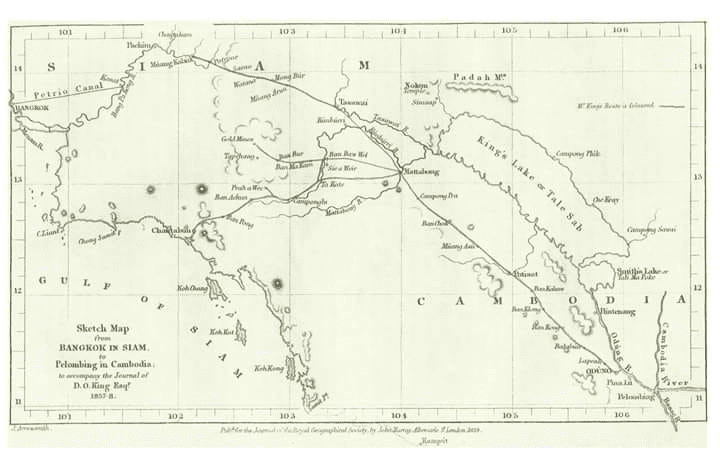

Sir, — Six months ago I returned to the city of Bangkok, in Siam, after nearly a year spent in travelling the unknown lands of Eastern Siam and Cambodia; and, at the suggestion of Sir Robert Schomburgh, H. B. M.’s Consul, I beg to hand you herewith a copy of the map of my travels, sufficiently interesting, I trust, to warrant its reception at your hands.

With the exception of M. de Pallegoix’s (*French Bishop of East Siam 1841-62) account of these countries, nothing has hitherto been published respecting them worthy of any confidence; and of the interior, beyond the city of Bangkok, the fanciful accounts of the natives served merely to excite a curiosity that a foreigner was unable to gratify. Permitted at last to investigate for ourselves, I became acquainted with Eastern Siam, and what is left of the old kingdom of Cambodia; and although the many reported marvels in botany and natural history were successively followed up until they were proved fables, still the geographical features of a new country are always of interest, and a few general remarks respecting them may not be unacceptable.

The eastern shore of the Gulf of Siam stretches from Bangkok to Chantiboon, and beyond Kampoot ; but the lofty range of mountains along the coast impedes communication, and the Petrio canal is exclusively used by travellers to or from the eastern provinces. This canal, 55 miles long, connects the city of Bangkok with the Bang Pa Kong river, and is made throng a flat, alluvial country, entirely devoted to the culture of rice.

The natives, like the rest of the Siamese, appear to be a branch of the Malay family ; the floors of their bamboo-thatched houses are raised some 4 feet from the ground ; their clothing simply a cloth round the waist ; and, whatever they may be engaged in, one hand is generally actively employed warring against the swarms of mosquitoes.

The canal joins the Bang Pa Kong river 20 miles from the mouth of the latter. This river, as you ascend, becomes narrow and winding ; cultivation is restricted to a strip of land on either bank at first, and then occurs only at intervals ; the inhabitants are few and poor, and nothing that can be called a village is met with until you arrive at Pachim. Here, and elsewhere in Siam, the traveller is struck by the immense tracts of land lying idle for the want of a labouring population ; emigration from China would soon remedy the evil ; but the Siamese rulers dread the introduction of any number of coolies, and restrict their importation.

Pachim is the residence of a governor of a province, and the traveller must land and show his passport : the officials are invariably civil and obliging, provided your passport comes from their superior in rank ; and custom, among themselves, obliges the foreigner to offer a small present before leaving.

The town of Pachim consists of some twenty bamboo houses, and was entirely destroyed two years since, a fire from the prairie consuming crops and all. The river here is about 40 yards wide, and during the rainy season, from July to November, runs out at the rate of 5 miles per hour. During the rest of the year there is a regular rise and fall of the tide here, and its influence is felt up to Kabin.

Leaving Pachim, the navigation of the river is tedious, being against a strong current, in the wet season, after which the river rapidly falls, and the channel is narrow and full of obstructions. An occasional glimpse of the mountains far off to the east and north is obtained, but the country along the river maintains its level character, and generally is densely wooded.

Twenty years ago, during a war with the Cochin Chinese, a military road was constructed from the town of Mooang Kabin across to the Pasawai river ; and although the bridges have disappeared, and the road is a mere wreck, still it is the only route across the country. Merchandise is conveyed in small but neatly-covered carts drawn by a pair of buffaloes; travellers using elephants ; and from this point over to the confines of Cochin China these latter animals occupy the place the horse does.

They are large, docile, and well trained, and are cheaper than anywhere else in the world, a full-grown animal being worth from 50 to 75 dollars (*around $1,565-$2,190 at today’s rates- cheaper than a Honda Dream!). About two-thirds of the males are (?) with tusks ; and in buying and selling the natives appear to think nothing of the value of the ivory.

Ten miles south-east from Kabin I visited a spot on the bank of the river, where anumber of natives were sinking shafts in search of gold : from all I could learn, but little had ever been found, and of late scarcely any.

Elephant-travelling over the military road is tedious and uninteresting. During the rainy season the streams are so swollen that the road is never traversed if it can be avoided ; and the want of water in the dry season is an ever present evil. The elephants soon become footsore and sick if pushed beyond 25 miles per day.

Travellers are rarely met with ; and solitary houses, 20 miles apart, only relieve the weariness of the route. One day’s journey from Kabin the road winds around the base of a mountain, but with this exception it is all a prairie— across to Tasawai occasionally broken and rolling, and then stretching for miles as smooth as a floor. The soil is of red sand, and the trees twisted and dwarfed in a manner I could never account for, until, caught, upon one occasion, by the fire that annually sweeps over these plains, among them, I had an opportunity of seeing how the young treeswere parched and shrivelled by it.

Bog-iron, which occurs frequently, is the only metal to be found on the road.

The provincial town of Mattabong (Battambang) is situated on both sides of a river of that name, in the centre of a large plain. The country, for nearly 100 miles around it, is flooded with water soon after the commencement of the rains ; travelling becomes impossible, except in boats, and wild animals are driven off to the mountains.

The existence of a large lake to the eastward has been reported to foreigners ever since their residence in Siam ; and in the map accompanying M. de Pallegoix’s work it is incorrectly inserted.

The native accounts of its size were found to be not far from the truth ; and I passed completely round the shores, everywhere being pleasantly diversified with forest and open prairie. The natives hold the lake in a sort of superstitious fear, its rough waves causing many accidents to their small canoes ; and squalls and waterspouts are of frequent occurrence.

During the months of January, February, and March, when the water has drained off the surrounding country, the lake appears alive with fish, and the inhabitants collect large quantities of them. From September to December the banks are overflowed from 10 to 20 feet deep. In the lake we failed to get bottom at 10 fathoms.

At the close of the dry season, in May, frequent shoals occur in its bed, and a boat drawing 2 feet of water is all its shallowness will allow.

At the northern extremity of the lake, in the vicinity of Simsap (*Siem Reap), was situated the ancient capital of Cambodia, no trace of which now remains, except in the Nokon temple, spared from destruction when the city was taken by the Cochin Chinese about a.d. 200.

The temple stands solitary and alone in the jungle, in too perfect order to be called a ruin, a relic of a race far ahead of the present in all the arts and sciences. A magnificent stone causeway, a third of a mile long, leads through an ornamental entrance up to the temple, composed of three quadrangles, one within, and raised above the other ; the lower quadrangle is 200 yards square, a broad verandah with a double row of square ornamented pillars running all round, with large and elaborately ornamented entrances at the corners and centres. It is built of a hard grey sandstone, without wood, cement, or iron in its composition, the blocks of stone fitting to each other with wonderful precision ; and the whole temple, within and without, covered with carefully executed bas-reliefs of Buddhist idols.

A few priests reside outside its walls, and the place is visited as a shrine by the Cambodians, On the eastern verandah a square tablet of black marble has been let into the wall covered with writing, and doubtless setting forth the mainfacts in the raising of the temple. The characters used are precisely similar to the present Cambodian alphabet, but so much has the use of the letters changed, that the present race cannot decipher it.

The Oodong river issues from the south end of Smith’s Lake, and is throughout a broad, majestic stream. The town of Poon-tenang (*Kampong Chhnang?) supplies the whole country with pottery, and from there to Oodoong scarcely a sign of human life is to be found. This city (Oodoong) is the present capital of Cambodia, the former city having been completely destroyed by the Cochin Chinese 15 years ago.

A wooden palisade, 20 feet high and 600 yards square, encloses a straggling collection of thatched houses, the residences of the nobles, in the centre of which a low brick-wall encloses the palace, mint, and arsenal. Everything bespeaks poverty and the recent ravages of war, but nothing could exceed the friendliness of the welcome extended to us by the King, and we were assured that foreign travellers would be granted every facility.

On the river below Oodoong the Roman Catholics have a mission establishment at Pina Loo, where we found a bishop and one priest ; and, descending the river, stopped at Pelomping (*Phnom Penh), a town on the borders of Cochin China.

This is a place of some little trade, raw silk, iron, dried fish, etc., being brought here from the Cambodia river, but the crowds of Cochin Chinese in the streets manifest anything but kind feelings : from a hill in the rear of the town the farther course of the river, as shown in my map, was noted, the Cambodia river here turning at a right angle to the eastward, with a breadth not less than 2 miles.

The elegant-road from Oodoong to Mattabong, like the rest of the roads, is only available during the dry season, and as far as Potisat (Pursat) winds through a hilly region. Near this town a large deposit of antimony is found, and also quarries of Oriental alabaster. The journey from Mattabong to the coast at Chantiboon usually occupied 6 days, the crossing of the coast range of mountains causing some delay, and affording nothing in scenery in return.

The botany and natural history of this region, so far as I could judge, afford nothing new or strange. The annual overflow of the plains is favourable to nothing except aquatic plants, and the waterlily is common everywhere. In addition to the white and purple lilies, and the common lotus, a bright cherry-coloured variety is found at Simsap. At Tenet Pra a lily was said to exist surpassing in size and beauty the Victoria Regia ; it was not in flower at the time of my visit, and the leaf of the plant was similar to the lotus. The cork-tree, wild nutmeg, licorice, and several varieties of India-rubber and gutta-percha are met with in the mountains, but not in sufficient quantities to be of commercial value.

My endeavours to meet with the tree producing the gamboge-gum were unsuccessful, it only being found in the mountainous region between Chantiboon and Kampoot.

The wild animals of the country are not so numerous as might be supposed ; the natives say that 20 years ago an epidemic swept off immense numbers of them ; and though tracks of deer, buffalo, wild cattle, and pigs are often seen, the animals are few and wild, and seldom met with. The wild elephant and rhinoceros are found in remote districts, and the tiger and leopard are heard of occasionally everywhere. The natives hold these last in but little fear, saying they have never been known to attack any one that faced them.

This country has long enjoyed a reputation for abounding in reptiles that does not belong to it. The skins of anacondas offered at Bangkok come from the northern provinces, and in all my travels I never saw but four snakes, all small.

The annoyances of travel are caused by smaller specimens of animal life. Ticks are common, and require constant care ; mosquitoes are often very troublesome ; and swarms of large horse-flies, that bring blood through an elephant’s skin, sometimes drive men and animals almost wild. But the greatest nuisance are the ground-leeches. The first shower of the rainy season brings into life a crop of leeches that grow to some three inches long, and infest the face of the earth. Warned by the rustle of the leaves, or the jar of the ground, of the approach of something living, they erect themselves on one end in the pathway, and swing round and round, trying to cling to what is passing by ; halt in the path, and you can see them coming in hurried spans from all sides ; drive your pantaloons inside your boots, and they climb up and get down your neck. To sleep in the open air is impossible, as they rest not at night, and animals of all sorts are covered with them.

The birds of the country are mostly of the wading species. Pelicans and ducks are common, but the adjutants and birds of the crane family are innumerable. Eagles and vultures are commonly found in the vicinity of carrion, and the shoehorn-bird of Sumatra is occasionally met with in the forest

So far as my experience goes, this land is poor in minerals. A little gold is obtained, but iron is the only thing found in any quantity ; no trace of coal anywhere. The mountainous region along the coast is doubtless richer, but is at present unknown.

With these remarks I commend the accompanying map to your attention, and remain

Your obedient servant,

D. O. King.

Submitted by Steve

More early travelers:

A good article by Steve to show that visiting Angkor was never a first. Thanks for posting the information.