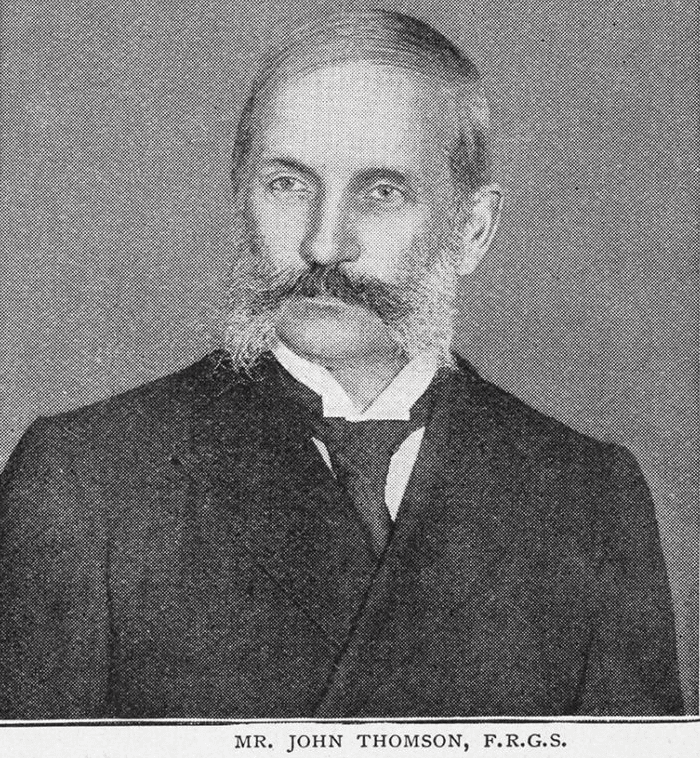

H.G. Kennedy and John Thomson, 1866

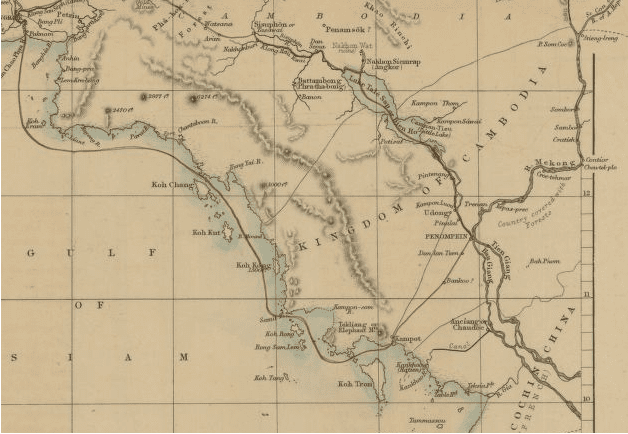

In January 1866 Henry George Kennedy of the British embassy in Bangkok and pioneering photographer John Thomson set off on an overland expedition to Angkor, and from there down the Tonle Sap to Phnom Penh and Kampot.

Inspired by Henri Mouhot’s account the ancient cities of Angkor in the Cambodian jungle, Edinburgh born Thomson embarked on what would become the first of his major photographic expeditions. He set off in January 1866 with Thai-speaking translator H. G. Kennedy, a British Consular official in Bangkok, who saved Thomson’s life when he contracted jungle fever en route. The pair spent two weeks at Angkor, where Thomson extensively documented the vast site, producing some of the earliest photographs of the temples.

Collection of Thomson’s Angkor Photos HERE

They stopped to visit Udong, but found it unprepossessing, Kennedy observing that “the palace consists of a few thatched wooden residences, scrupulously clean, but wholly unworthy to be the dwelling place of a monarch.” But the enclosures and lotus gardens were almost completely deserted, for the king had gone, taking with him everyone from court officials to bazaar traders.

They anchored at Phnom Penh on the night of 27 March, 1866, at the centre of “a string of densely packed bamboo huts on poles strung out along the right bank of the Tonle Sap river. The presence of the Cambodian court, which has lately fixed its residence at Penompein, is working a great and rapid transformation in the condition of the town. A broad and solid causeway, stretching through the principal quarter, will shortly supplant the original narrow thoroughfare; a handsome and substantial palace is in the course of construction; and while the Mandarins are fast filling the eligible sites with private residences, the booths in the market are giving place to commodious brick dwellings which traders are erecting there“.

The “broad and solid causeway”, newly paved with crushed brick, was the Grande Rue, and Thomson gives a vivid description of “the most animated and interesting scene in Cambodia”:

“Sellers are busy everywhere … majority of the merchants are Chinamen … elephants and buffalo wagons … Cambodian drivers … women in picturesque costumes … fleet bullocks covered with gingling [sic] bells … low stalls alternate with square mats spread on the ground … noisy gambling … loathsome leper brushes past … the prostration of the multitude while a noble is passing.

King Norodom, “a young man of about thirty years of age, and of exceedingly amiable manners,” was a hospitable host: The King treated us with great courtesy, assigning us a house within the palace grounds, and entertaining us repeatedly at his table, where excellent dinners were specifically prepared for us in completely European style. The fact is, his majesty had a French cook in his pay….

They stayed eight days in Phnom Penh. They watched a display of the royal ballet, somewhat tedious after the initial novelty wore off, and on the morning of their departure they were invited to watch the royal guard at morning drill. Norodom regretted that he could not order his men to put on their formal uniforms for this in case the French believed he was offering honours to a visiting British diplomat, leading Kennedy to conclude that he was completely under the thumb of his protectors, who “have introduced several of their employés into the royal service, themselves disbursing the major portion of their salaries.”

One of these was Paul le Faucheur (Kennedy spells it as Foucheur), the self-described architect of the new palace, who informed them that the royal income was about a thousand pounds a month; Kennedy believed this was probably an under-estimate designed to mislead the prying Britishers. Sivotha and Sirivong were still in Bangkok, but Sisowath had been transferred to Saigon. “He still resides under French surveillance at that city, greatly to his Majesty’s annoyance and apprehension,” for as Norodom confessed to Kennedy, “if his brother … were to come into the country, and there a general wish for his elevation to the throne [as Second King], it would be his duty to sanction the measure.”

Thomson took two historic photographs of Norodom during this visit, almost the first ever. (The very first, taken in Saigon during a visit in late 1864, has disappeared, although an engraving made from it still exists). One shows him in the costume of Khmer kingship, seated on a carved throne in front of an Oriental curtain with the spired crown on his head, the golden slippers on his feet, and the sacred sword cradled in his lap; the other shows him in the dress uniform of a French field marshal, all epaulettes and braid, seated in an armchair with a cocked hat on his lap. No doubt the photographs signal the king’s pride in his Khmer kingship and his confidence in the French alliance, but between them they mark the two sides of what was rapidly becoming a divided identity. “Having decided to proceed to Kampot, and thence by sea to Bangkok, we took leave of his Majesty at mid-day on the 4th of April, and set out with elephants and buffalo-carts to complete our journey.”

Thomson returned to Britain in May or June in 1866, and later lectured to the British Association and published his photographs of Siam and Cambodia. He became a member of the Royal Ethnological Society of London and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society in 1866, and published his first book, The Antiquities of Cambodia, in early 1867.

Thomson returned to the Far East, where he set up a studio in Hong Kong and embarked on several expeditions to remote parts of China. Later settling in London, he began taking photographs of street scenes, publishing ‘Street Life in London‘ in 1877, and photographing British high society, including the British royal family and Queen Victoria herself.

He retired to Edinburgh in around 1910, and died of a heart attack in 1921 at the age of 84.

“Lack of time and opportunity constrains the gifted traveller, too often to trust to memory for detail in his sketches, and by the free play of fancy he fills in and embellishes his handiwork until it becomes a picture of his own creation. An instantaneous photograph would certainly rob his effort of romance, but the merit would remain of his carrying away a perfect mimicry of the scene presented, and an enduring evidence of work faithfully performed.” John Thomson, ‘Photography and Exploration’, Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography, Vol. 13, No. 11 (Nov., 1891)

Submitted by Philip Coggan as “a chapter from the thing I’m working on“, extra info sourced by Steve