This continues from PART ONE

After the election victory of Sihanouk’s Sangkum in 1955, the new government soon facing suspicion from neighboring Thailand and South Vietnam. Both nations were fighting communist insurgencies and were fearful that a weak, but outwardly ‘neutral’ Cambodian regime could be used to shelter communist fighters and equipment. The Prince did little to allay these fears, especially after striking up a lifelong friendship with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai after the pair met in Bandung, Indonesia in April 1955.

In February 1956, Sihanouk declined an offer by the Philippines to join with Thailand and a number of western countries in the anti-communist (and somewhat inaccurately named) SEATO alliance. A few months later on April 21, 1956, the Chinese government promised economic assistance of $22.8 million over a two-year period to the Cambodian government. The Soviet Union then provided diplomatic recognition to Cambodia on May 18, 1956.

Ambassador McClintock wrote the following to Washington on May 31, 1956

“To increase aid to Cambodia under circumstance of Chinese impending assistance would merely encourage Prince Sihanouk in his cocky assumption he can have best of both possible worlds by playing off United States against Communist China. Furthermore, it would provoke reactions on part of our allies in Southeast Asia. It is not likely in any event Congress would increase aid funds to Cambodia, nor is it needed either economically or politically at present to meet ChiCom. It is further true ChiComs have cast gauntlet where we have opportunity to beat them at their own game.”

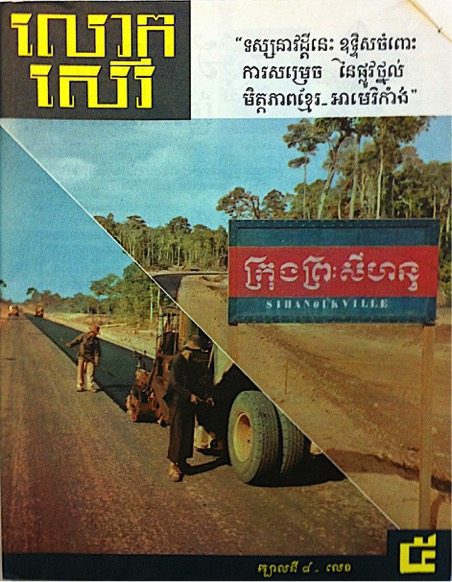

The Americans stepped up ‘soft diplomacy’ with projects such as the Khmer-American Friendship Highway (now National Rd 4), although congress was told that both military and economic aid would be reduced after such initiatives had been completed.

To begin with Cambodia saw the best of both worlds, with aid from America and France along with the Sino-Soviet bloc (although slow to begin with from China) seemingly supporting the idea of a ‘neutral’ kingdom in a volatile region. This did, however, cause issues with both the economy that was becoming bloated on ‘free money’ and dissatisfaction among some of those in the elite who were worried on the influence Chinese ‘advisors’ may be having on the sizable ethnic Chinese minority in the country.

A January dispatch was sent by Ambassador Strom, who replaced McClintock in October 1956. Although outwardly positive, he had stark warnings for the coming year, including:

“There will inevitably continue (in 1957) to be some amount of unpredictable and erratic veering of policy, since it cannot be expected that there will be any fundamental change in Sihanouk’s personality and modes of action. How significant such veering will be will depend in large part on the pressures to which Sihanouk believes that he is subject. Within the framework of neutrality, it is still highly possible that some actions may be taken which will further increase the existing Communist threat; foremost among these would be any moves toward formal recognition of Communist China or North Vietnam.”

Meanwhile, Son Ngoc Thanh- still aided by Bangkok- remained with his small band of fighters along the northern Cambodian border with Thailand. A planned coup against Sihanouk was now afoot- exactly who was involved, and what their objectives were, is still subject to debate.

The Failed Coup

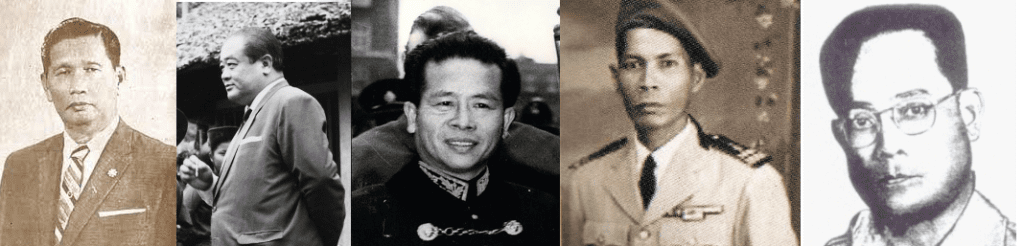

The Bangkok Plot, also known as the “Dap Chhuon Plot” was allegedly initiated by right-wing politicians Sam Sary, Son Ngoc Thanh, along with the Siem Reap based warlord and governor Dap Chhuon and the governments of Thailand and South Vietnam with possible involvement of US intelligence services.

In December 1958 or January 1959 the plotters were said to have met in Bangkok with (according to claims later made by Sihanouk) Thai leader Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat and South Vietnamese representative to Cambodia Ngo Trong Hieu and several CIA operatives.

The plot was to be a coordinated series of actions designed to close off Cambodia. Chhuon, from his base in Siem Reap would seal off the Western provinces and declare an autonomous zone, while Son Ngoc Thanh would carry out guerrilla operations throughout the country. Ngo Trong Hieu would recruit Khmer Krom on the Cambodian border with South Vietnam, while regular Thai and South Vietnamese forces would move troops to the borders. If Sihanouk did not see reason, resign and appoint Thanh to head a pro-Western government, he would be overthrown.

The intelligence services of France, the Soviet Union and China immediately informed Sihanouk of the conspiracy. Cambodian security forces moved in on February 21, 1959.

Son Ngoc Thanh escaped capture, but Dap Chhuon was apprehended in Siem Reap, interrogated, and died “of injuries” in unclear circumstances before he could be properly interviewed. Sihanouk later alleged that his Minister of Defence, Lon Nol, had Chhuon shot to prevent being implicated in the coup. Images of his bloodied body were posted on the streets of Phnom Penh. Sam Sary later fled to Thailand where he was given refuge by the Thai military, and later disappeared in mysterious circumstances in 1962.

Inside Chhoun’s villa were 270 kilos of gold bullion, supposedly for paying his troops and bribes to local officials when the plan got underway. A radio transmitter with two Vietnamese technicians and an attaché from the US embassy named Victor Matsui were also found on the property. The Americans later explained that Matsui had merely been keeping the embassy informed, but could not say why, unlike other countries, had not forewarned the Cambodians.

The Americans denied any involvement, although US officials were obviously aware of the possibility of a coup, with Alfred Jenkins, Deputy Director of the Office of Southeast Asian Affairs, writing to Walter Robertson, the Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs on August 1958, where he named Thanh as a potential candidate to depose Sihanouk.

The failure of the plot reenforced Sihanouk’s distrust of his neighbors and the US.

After the death of Chhoun, Sihanouk described the foiled coup attempt in a speech

“…drawn up by a marshal, head of the government of a neighboring kingdom, by the envoys of a neighboring state, and by Son Ngoc Thanh. Like nocturnal birds of prey blinded by the hunter’s torch, dark schemes hatched in secret will come to nothing once they are dragged out into the light.”

The Plotters

The lead-up to the Bangkok Plot saw deepening distrust from between all the players, not least Sihanouk.

Dap Chhoun- the former Issarak, turned Sihanouk’s enforcer- had been demoted from his role in the Interior Ministry and Security Services, but still had de-facto control over Siem Reap. He informed Ambassador Strom in October 1958 that he had ‘three battalions of seasoned fighters’ under his command in the north, still officially part of the Khmer Royal Army, along with the loyalty of many officers and the Royal Guard in Phnom Penh.

His dismissal, and disgust at Sihanouk’s leaning towards China and the Soviet bloc, saw the vehemently anti-communist turn to the US, who were, from reports, sympathetic, but discouraged any actions which might play to China’s advantage. Chhoun even had an audience with Sihanouk’s mother Queen Kossamak, whom was privately concerned about his warnings of communist infiltration, but unable to influence the prince. Instead, Chhoun discovered a friend in President Diem in Saigon.

There was a deep and mutual animosity between the Cambodian and South Vietnamese leaders throughout the mid to late 1950s and beyond, with both having valid cases.

Sihanouk, like his successors Lon Nol and Pol Pot, regularly espoused anti-Vietnamese rhetoric and promises to reclaim the ‘stolen land’ of Cochinchina, which was popular among his supporter base. Sihnaouk had requested Chinese aid and technical advice in 1957-58 to map and demarcate the eastern border areas, no doubt with hopes to find in Cambodia’s favor.

Just a few years earlier, Cambodia had seen large numbers of Viet-Minh inside the borders during the French war, and although they had officially departed following the Geneva agreements, there were fears that many still remained, or that they could return easily. Sihanouk’s policy of neutrality was seen as a weakness that could be exploited by Hanoi as a means to attack the Saigon regime- either with or without the Prince’s consent. This was not so far fetched, as, in the mountains of Laos by this time work had already begun on a logistics route from the North- later dubbed ‘the Ho Chi Minh Trail’.

On the other hand Sihanouk genuinely feared further South Vietnamese expansion into the kingdom. South Vietnamese forces had entered an area of Stung Treng province in June 1958, and remained inside Cambodian territory, despite protests from Cambodian Prime Minister Sim Var (a former close associate of Thanh), who appealed to the United States to intervene. Sim Var warned Ambassador Strom that, if the matter was not resolved, Cambodia would be forced seek help from “other friendly powers.”

In a speech Sihanouk gave two weeks later, he said “For our tranquility we ought to choose a great ally who is not too far from us and who is ready to aid us.”

Just days later, on July 19, 1958, Cambodia formally recognized the People’s Republic of China. In protest US Ambassador Strom was recalled from Phnom Penh.

Strom, for the most part, had sympathized with the Cambodian position, exchanging heated telegrams with the State Department and Ambassador to Saigon, Elbridge Durbrow. With tensions rising in the summer of 1958, Dubrow wrote

“….Cambodia does not appear to be at crossroads but rather somewhat past that point along the road to the left. Sihanouk has already recognized USSR and accepted Soviet aid and for most practical purposes has also recognized Communist China.”

However, Dubrow tried to dissuade Diem from actively trying to remove Sihanouk by force and replacing him with Son Ngoc Thanh by pointing to Sihanouk’s popularity- especially among the rural majority, and any attempt to overthrow him would push Cambodia even deeper into communist influence.

After a meeting in Saigon, Durbrow commented that Diem’s “insistence on growing opposition (from Thanh and his followers) may indicate he actively trying operate in this field.”

Son Ngoc Thanh was still operating from the border area of Surin Province, Thailand and O’Smach. Although still considered a mortal enemy by Sihanouk, in reality he was seen as little more than a nuisance by many inside Cambodia. With the Democratic Party a fading memory, his ‘Khmer Serei’ organization held little popular support, and the anti-Sihanouk propaganda radio shows broadcast from across the border went mostly unnoticed.

Writing on the issue the Ambassador noted “Son Ngoc Thanh can hardly be considered a likely leader [of] these disorganized groups. He is widely respected for his fight for Cambodian independence, but . . . he is considered increasingly disgruntled man who has abandoned principles and only seeks return to power by any means. He has no organized following.”

Yet, recognition of China by Phnom Penh appeared to pull together the plotters together.

Numerous CIA and State Department files point to American attempts to dissuade the South Vietnamese from interference in Cambodia, but compelling evidence, both circumstantial and physical, showed there was at the least knowledge of- if not involvement, in the plot.

The gold had arrived in Siem Reap on an Air Vietnam flight, a CIA man with equipment was captured on the ground while the governments of Thailand and South Vietnam were openly calling for a change of leadership in Phnom Penh- it wasn’t hard for Sihanouk to reach conclusions.

The Aftermath- Thanh Rises Again

With Dap Chhoun dead, and Sam Sary soon taking flight (and mysteriously vanishing), Son Ngoc Thanh was now the main anti-communist rebel who was able to keep a relationship with Bangkok, Saigon and Washington. His ‘Manifesto of the Khmer Serei’ released in late 1959 directly accused Sihanouk of ‘communizing’ Cambodia. This may have been a genuine political statement, but was also likely to have been a somewhat cynical exercise to gain further attention from the US.

At the start of the new decade, Sihanouk was in a far more precarious position than he had been in the years since independence. Surrounded by enemies on the borders and enemies from within, Thanh- although a nuisance, could likely be kept under control by Sihanouk’s forces, as long as he remained in the northern jungles.

Thanh, with increasing CIA support and the blessings of Saigon, began moving his men down to his own homeland in the Mekong Delta, and recruiting new fighters from ethnic Khmer Krom communities. This updated Khmer Serei (Free Khmers), would loosely be aligned with the CIA sponsored Civil Irregular Defense Group (CIDG), who would be trained, supplied and fight alongside the American Special Forces and the Mobile Strike Force Command, aka MIKE Force.

Read more about Thanh and the Issarak movement

By History Steve- sources include- The Office of the Historian, CIA Archives, Robert Turkoly-Joczik, Matthew Jagel, Department of State “Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955–1957/1958-60”.