By 1956, the nationalist, long-term rebel and sometime politician Son Ngoc Thanh had seen the fragmentation of the Issarak movement he helped found in the 1940’s.

Many of his former right-wing comrades-in-arms had defected to the Sangkum movement headed by Sihanouk, while the left-wing factions had either fled to Hanoi, gone into legitimate politics or became organized into underground cells.

After his own attempts at reconciliation with Sihanouk- who from late 1955 was essentially running a one-party autocracy- failed, Thanh remained hiding out along the Thai border in the north. From there, Thanh continued to broadcast anti-Sihanouk propaganda and organize minor protests- which may have upset the Prince, but had relatively little impact on his popularity.

Following Sihanouk’s abdication in March 1955, most of the now-Prince’s political rivals had been vanquished- either brought into the Sangkum movement, exiled or forced underground.

The Democratic Party- once the dominant force in Cambodian politics turned to the left after being taken over by leftist intellectuals such as Keng Vannsak (formally of the AEK student association in Paris and a friend of Pol Pot (although not necessarily sharing the same ideologies), along with more radical students who had returned from France.

Led into the 1955 elections by Prince Norodom Phurissara (Sihanouk’s cousin), the candidates faced intimidation- Keng Vannsak, standing for election- was fired upon by government agents on the eve of the poll, and then jailed during the voting period. In Battambang, the party’s office was ransacked by a mob.

The Democrats came away with just 12% of the vote amid widespread vote-rigging and voter intimidation carried out by Sangkum henchmen including Dap Chhoun and Lon Nol.

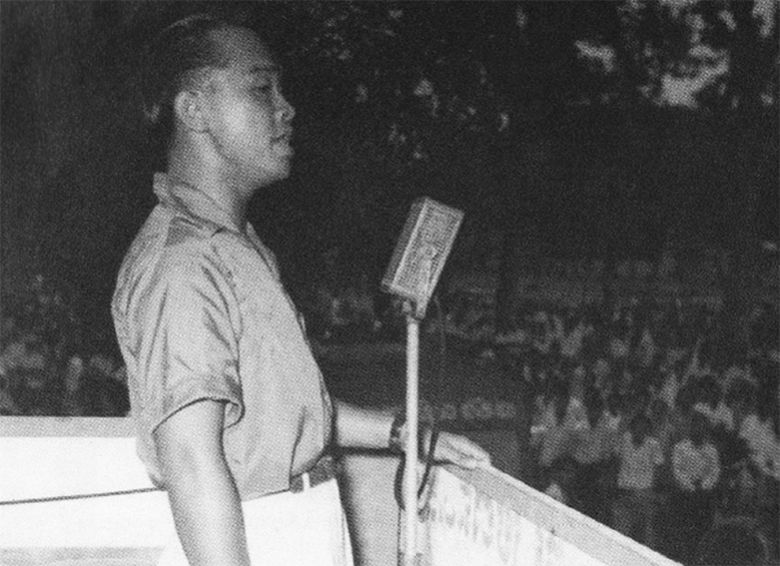

It appears Sihanouk was taking no chances with Thanh, especially after his gamble in allowing the nationalist to return in 1951 backfired. Thanh- who had been exiled under house arrest in France- was allowed to return after Sihanouk lobbied the French administration. The warm welcome Thanh received from the thousands who greeted his arrival at Ponchentong, including government officils, reportedly rankled the King, who was not expecting such a showing of popular support for the former minister and nationalist figurehead after so many years outside of the country.

Thanh remained in the northwestern jungle after independence, forming a new rebel group which cultivated links with Thailand and later the US and South Vietnam. India- which headed the International Commission for Supervision and Control (ICSC), a peace-keeping force set up in Indochina after the Geneva Accords- also looked upon Thanh with some favor, despite the growing closeness between Sihanouk and Indian Prime Minister Nehru.

The February Referendum

Sihanouk, taking much of the credit for independence and Geneva was unwilling to risk allowing Thanh to return to politics. The chances of him restoring the Democrats should he be allowed to lead the party were too high. With international support and that of the educated Cambodian class, Thanh could have been a serious threat to the prince’s hold on political power.

The CIA became aware of Thanh’s anti-communist stance around this time, after previously labeling him as a Viet Minh sympathizer. A CIA report from January 1955 concluded that Thanh had considerable support from some Indian commanders in Cambodia, which was why Sihanouk did not make any serious attempt to arrest or send in forces to deal with him. Noting that:

The Cambodian government decided on 22 January to hold national elections on 17 April rather than in June (*later postponed) . This decision reflects the king’s determination to head off the budding political campaign of the ex-rebel leader Son Ngoc Thanh,

The king’s belief that the opportunistic Thanh is the principal threat to himself and to the Cambodian monarchy has been stimulated by the sympathy which Indian officials have shown Thanh. Indian interest in Son Ngoc Thanh is out of proportion to his real status in Cambodian politics, and is probably based on the belief that, as an antimonarchist, he exerts a desirable influence.

As early as October, an Indian truce official said he and his colleagues felt Thanh would be an ideal national leader, under whom the country could experience the kind of democracy which India favored. A recent letter from Thanh to the king was reported drafted by the Indians.

The Cambodian government attaches great importance to Indian friendship, and is thus restrained from taking direct repressive measures against Thanh. The king is planning to meet this dilemma prior to the national elections by holding a popular referendum on 7 February on whether or not the king has fulfilled his pledge to achieve peace and independence. The probable affirmative results will have the effect of reducing Thanh’s influence and discouraging Indian support.

The February 1955 referendum was cast over 2 days. The question from Sihanouk was simple; “Have I kept my promise to give you total independence?”. It was literally black or white, with those in agreement with Sihanouk’s question voting with the latter colored ballots. Despite the result being a forgone conclusion, efforts were made by the authorities to make sure the vote went to plan as intended. At least one newspaper- the Khmer Thmey- was closed and several known Thanh sympathizers were rounded up and detained. Ballots were cast in the open, in front of officials and other voters.

The final count was registered as 925,667 white (in support of Sihanouk) and 1,834 black- although many of these were said to have been cast by ‘mistake’.

Thanh, cast into both the political and literal wilderness, and with support from Bangkok, set up a base on the Thai border with around 2,000 followers. Shortly afterwards the base was visited by a US official operating out of Bangkok- he was later given a dressing down by the US Ambassador in Thailand for acknowledging its existence.

Sihanouk’s next move was a game changer. Without warning, and to the great surprise of those around him- including the Royal Family- on March 2, 1955, he announced his abdication in favor of his father, Sumarit.

There were several obvious reasons behind this unexpected action. Elections for the National Assembly- a key agreement at Geneva- had already been postponed to September. In all likelihood, Sihanouk would have preferred to do away with the National Assembly all together, but was facing strong criticism from the Indian, Polish and Canadian members of the ICSC.

Instead, with his abdication he could capitalize on his popularity among the masses- he was still a direct descendant of the ‘God-Kings’ of Angkor- and also deliver a knock-out blow to the educated class calling for a constitutional monarchy. With the creation of the ‘Popular Socialist’ Sangkum Reastr Niyum movement and some political maneuverings, Prince Sihanouk was able to contest the postponed 1955 elections in the face of weakened opposition and finally take control of the National Assembly.

An extract of the abdication speech, published in The Gettysburg Times, March 2 1955 quoted Sihanouk:

My people are not unaware of the work accomplished by their King in the past three years, nor of the importance of the constitutional reforms which I envisaged to avoid a return to chaos. Certain political parties, among them the Democratic party of Son Ngoc Thanh, have intervened with the [ICSC] to prevent me from carrying out my work. That is why, today, I announce publicly my intention to abandon power and to step down from the throne in order to live among my people a life that will hereafter be humble like that of my subjects. I will retire to the country and I will refuse to take with me anything from the palace

The US Ambassador to Cambodia, Robert McClintock- in Manila at the time of the abdication- reportedly commented “That dirty rat, my King has run out on me”.

US policy toward Cambodia was confused. Reports suggested that Sihanouk had support from the masses, yet ‘anyone who speaks French’ (i.e. the educated class) were inclined to worry about the apparent grab for power made by the now-prince. There were concerns in Bangkok and Saigon that Cambodia was in danger of becoming a weak link in the fight against communism, and that Sihanouk was either unwilling or unable to set clear policy on the issue.

Thanh was seen as a possible successor who had international support- especially from some influential Indians. Although now vocally anti-communist, his links with the Viet Minh and Cambodian left-wingers from his days in the Issarak movement were still of a concern to Washington. However, it was also noted by the Thai government that by rejecting or ignoring Thanh, the CIA and other intelligence outfits ran the risk of pushing his group towards communist support. So, instead, a duplicitous arrangement began to hatch, with outward support given to Sihanouk and, gradually, covert support to Thanh- in case, as it was feared, the former was overthrown in a coup or moved too close to the Communist bloc. If this happened America’s other man was waiting in the wings as a replacement to avoid a communist takeover.

The elections, twice postponed by Sihanouk to much protestation by the ICSC, finally went ahead in September 1955. Following dozens of reports of violence, voter intimidation, arrests of Democratic Party and the communist Pracheachun Party members and unashamedly open ballot stuffing, the Sangkum won by a landslide, taking all 91 seats and 82% of the vote. Women were given the vote, although any citizen who could not prove that they had resided at the same address for the previous three years was excluded- a move seen at targeting former rebels.

The US recognized the vote as ‘fair’- mainly as a Sihanouk dominated government was preferable to one which had leftist or communist elements. However, the Prince’s growing friendship with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai and the rejection of an offer to join the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) soon gave Washington concern.

Many former civil servants and opposition activists who had not joined the Sangkum and were, in some part persecuted by the movement and the secret police, understood they had no future under Sihanouk and drifted north to join Son Ngoc Thanh.

A disorganized mixture of former Issaraks, anti-monarchists and those disgruntled by Sihanouk’s takeover of power, this group may well have faded into obscurity if it had not been for sponsorship from the staunchly anti-communist and pro-US government in Bangkok. The seeds had been sown for what was to become an elite CIA sponsored guerrilla force- the Khmer Serei.

History Steve Sources include: Steven Heder, Robert L. Turkoly-Joczik, Matthew Jagel, Dr. Henri Locard