*This originally was published in CAMDEN NEW JOURNAL in 2017

London: When the Khmer Rouge took over the Cambodian government in 1975, the effects would ripple around the globe – and have an unexpected impact on the lives of a small group of people living in a squat in Belsize Park.

Musician, artist and writer Dave Tomlin was staying in a house in Lancaster Grove and, soon after Pol Pot’s army had won the civil war, he was served an eviction notice that would mean in 10 days he would be homeless.

As he had done in the past when he needed to find a new place to stay, he set out walking the streets, on the look out for abandoned homes. His rambling route brought him down Avenue Road in Swiss Cottage – and it was there he noticed a large house with telephone directories piling up by the front door.

“It was always a sign that a place had been empty for a while,” recalls Dave – and would lead him to setting up what he and his friends called The Guild of Transcultural Studies in what had been the Cambodian embassy. It was to become a centre of counter culture art and music in north London for 15 years.

“The Cambodian government was kaput,” says Dave, who had played the saxophone in jazz bands in the 1960s, become involved in the free school movement and performed at various clubs and gigs in the hippy troupe, The Third Ear Band.

“There was Pol Pot but he wasn’t recognised so it had fallen into this in-between state,” he says of the building.

Dave climbed in alone at night, fitted new locks on the doors and friends began to move in. He made a brass plaque proclaiming it was home to The Guild Of Transcultural Studies to give it some sense of respectability. Artists, musicians and philosophers took rooms and the grand salon became an event space.

The book is split up into 220 small chapters, rapid-fire short stories that are anecdotes about everyday life, the trials and mishaps and a huge dollop of wit and humour about the absurdities of the counter culture movement and the types of people it attracted. He also fills the pages with asides about his life as a wandering hippie, regaling us with various adventures such as travelling through the West Country with a horse and cart, getting marooned on the island of Fernando Po off the coast of Africa, embarking on a quest for laughing powder, and all told with huge humour and lyricism.

Meandering through the halls are such figures as the author of Alternative London, Nicholas Saunders, photographer Hoppy Hopkins, Chilean refugees fleeing Pinochet, Beat poets, a musical instrument inventor, and much, much more.

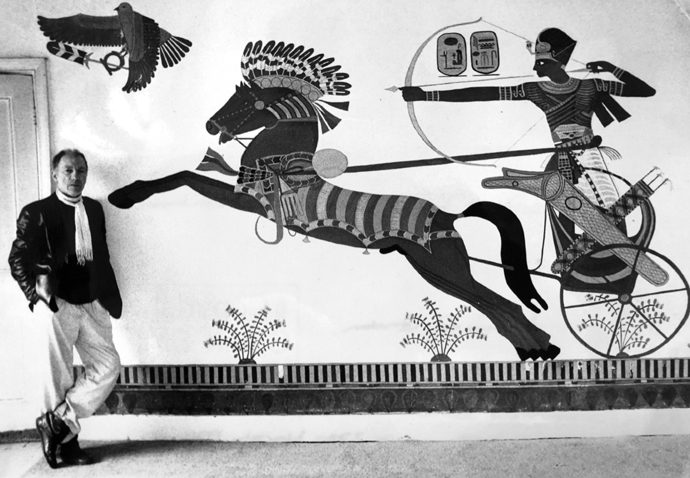

Dave Tomlin

“When you open up a squat, you have a little bit of control,” he says. “You can decide who comes to live there.”

It meant Dave and fellow squatters could use it as a resource to encourage the things they were interested in – and become patrons of the arts. Dave had a long-standing interest in Indian music and thought, so the salon would host gigs for musicians playing Eastern music, for example.

“‘I am trying to write a play,’ someone would say, ‘I need somewhere cheap and quiet’,” says David. “We’d offer a room – and we could then keep out people who would be antisocial in their behaviour and cause trouble for others.”

They discovered the Cambodian diplomatic staff had left in a hurry, leaving things like Cambodian typewriters, books on international law and headed notepaper in various rooms. Many rooms were richly furnished, with huge upholstered armchairs and couches, chandeliers, large gilded mirrors and pictures of Asian dignitaries.

“I spent the first few days mulling over the chances of hanging on to this stately pile,” he remembers. “It is obviously outrageous: squatters are confined to derelict and sub-standard buildings. You can’t squat a palace.”

After settling in, they were disturbed one day by fiercely angry bureaucrats from the Foreign Office.

“They claimed it fell under their jurisdiction but that was questionable,” he says. “We saw them off.”

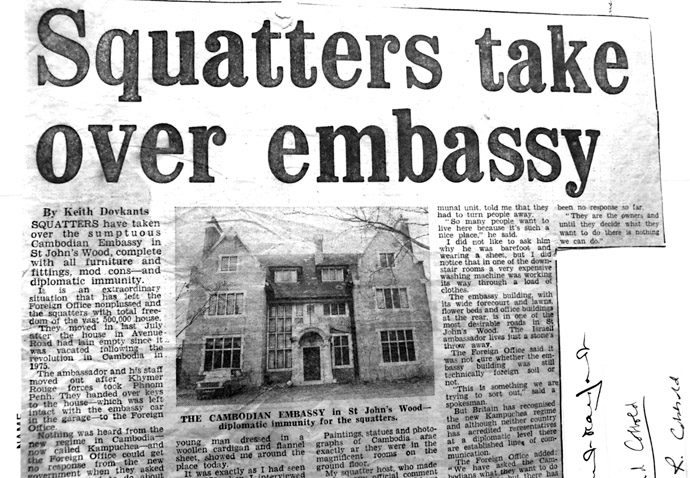

How the Evening Standard reported the incident

The book takes us through 15 years of life at Avenue Road, from the strange tics of living somewhere with so many others, the arty happenings, the philosophers, sages, radical metaphysicians, poets and the like to the battles with authorities and utility companies trying to get them to leave.

Eventually, it came to an end.

“I didn’t want to claim the house using the adverse possession law,” he says. “We wanted to give it to the Cambodian government when they finally came back. It was a dream we had of handing over the keys to its rightful owner. The Foreign Office finally pushed hard enough and in the final case I was faced with a choice where I would have to have claimed adverse possession or leave.

“The normal time period is 12 years, but because it was a diplomatic situation it could be claimed by the Crown and we were told we would have to have been there for 25 years to do so.

“It had become a bit of strain. I was running it and I had to handle that. I was ready for a new start.”

• Tales From The Embassy: Communiques from the Guild of Transcultural Studies. By Dave Tomlin, Strange Attractor Press, £15.99.