This continues from PART ONE and PART TWO

1953 will be remembered as the year that Cambodia achieved independence after 90 years of French colonial rule. The year began with phase II of the ‘royal coup’, a few months after King Sihanouk had reportedly told the US chargé d’affaires Thomas Gardiner Corcoran, that parliamentary democracy was unsuitable for Cambodia.

Sihanouk had pointed out the differences between himself and the Issaraks as both sought independence.

“The Issaraks claim to be fighting for Cambodia, and so do the Army and the police. As Son Ngoc Thanh has said, all Cambodians must join together on one side. Only, one has to agree on what side….that the so-called heroes have never done anything constructive, that they have only brought disorder, disunity, and ruin while shouting that France has not given real independence. They speak of public servants sucking the blood of the people, but they help themselves to the wealth of the country without any vote or control. If the Issaraks win, there will be unbridled arbitrariness.”

On the other side, an Issarak named Nguon Hong wrote against French rule in a propaganda piece entitled, “Who is the Thief?”

“The French have robbed us for eighty years… through high taxes, stolen resources, arrested the innocent, and driven the country into poverty….. French teachers, on a daily basis, urge students to hate the true Cambodian patriots. . . . for example, Son Ngoc Thanh, but that only drives them to love and respect Thanh more.”

A CIA Information Report dated December 31, 1952, on Son Ngoc Thanh found he was camped across the border from Ban Dan, Thailand. According to the report: 200 armed and trained guerillas comprised of the main force, with two units being recently dispatched to Kompong Speu and Kompong Chhnang. An advanced guard camp of twenty-five men was located two kilometers from the main camp. Much of Thanh’s arms were old Japanese weapons, including rifles, ammunition, and grenades. Two radio stations, from which he broadcasted his announcements to the nation, were located on nearby mountaintops. Thanh also secured a supply-line from Thailand, which supplied him with additional arms and equipment. The Cambodian population in Bangkok and Surin, Thailand, were great supporters of Thanh and agreed to contribute twenty-five baht per head to Thanh’s group of rebels. The rearmament from Thailand was being done in preparation for a supposed planned attack on Siem Reap the following month.

The Royal Crusade

January 11, 1953: Almost 7 months after dissolving the elected Democratic Party government, the King, who had been acting as Prime Minister, demanded extraordinary powers from the National Assembly.

January 13, 1953: Sihanouk dissolved the National Assembly and declared a national state of emergency. Nine deputies of the Democratic Party were arrested and charged with collaborating against the state with the Issaraks and the Viet Minh.

The following day, January 14, the failed student Saloth Sar returned to Cambodia after his journey from France via Saigon.

January 24, 1953: Trusted Sihanouk loyalist Penn Nouth was made Prime Minister of the new emergency government. After 3 days, a National Consultative Council was formed and King Sihanouk began his ‘Royal Crusade’ for independence and left on a world tour lobbying for independence, starting first in France- where he also persuaded the French government to crackdown on the AEK- followed by Canada, the USA and Japan.

After negotiations, wrangling and displays of petulance, the French government- facing problems across much of its vast colonial empire- agreed to full independence for Cambodia. The reasons for the decision are myriad and complex- certainly Sihanouk’s ‘crusade’ had a superficial impact, but only one amongst countless others, which in the author’s own opinion included;

Economics– France was still reeling from the effects of World War II. Jean Monnet, head of Le Commissariat général du Plan (the General Planning Commission), had formulated his eponymous plan in 1946, which was succeeded by the Shuman Plan in 1950. In a nutshell, these economic plans relied on American backing and European co-prosperity and trade. This began the Les Trente Glorieuses (‘The Glorious Thirty’) years of French domestic economic growth, but called for huge changes and restructuring of the French economy.

Colonies were an unnecessary expense- especially unprofitable ones like Cambodia (when compared with others such as Algeria and Vietnam, which were deemed by the right as ‘worth fighting for’). French Communists and Socialists were already- broadly speaking- anti-colonialism.

Cambodia had very little resources. There was the huge rubber plantation at Chup, but even this was dwarfed by those over the border- owned and managed by French companies such as Michelin.

Social- It must be noted that unlike other French colonies, Cambodia’s make-up was relatively simple, with the vast majority of the approximate population of 5 million made up of ethnic Khmer. After the slaughter seen after the partition of India in 1947, and the possibilities of more such incidents occurring among the multiple ethnic groups in France’s African empire- Cambodia would have appeared-on paper- to have offered a relatively smooth transition.

French agents from within Viet Minh controlled Cambodian areas reported that local people were being urged to fight for ‘Buddhism and Angkor Wat’ rather than being indoctrinated in Communist theory. It was assumed by many, that, with the French out of the way, the Cambodian people would unite behind the king- still seen as a divine ruler countryside people.

The Cambodian elite were all French educated, and even many ardent nationalists like Sam Sary were still Francophiles at heart. Sihanouk himself attended military training at the elite École de cavalerie Armoured Cavalry Branch Training School in 1946, and again in 1948 and was a reserve captain in the French army. These were people that France could do business with in the future

Political: The French election in 1951 had seen the French Communist Party (PCF) winning over 26% of the popular vote, while the Gaullist Rally of the French People won just under 22%.

To gauge the scale of popularity for the Indochina issue, a public opinion poll from February 1954- shortly after Cambodian independence showed only 7% of the French public wanted to continue the fight in Vietnam.

In the US, King Sihanouk called the French governments bluff in an interview with Michael James of the New York Times, published April 19, 1953.

“Norodom Sihanouk, King of Cambodia, one of the three associated States of Indo-China, warned in an interview yesterday, that unless the French give his people more independence in the next few months, there is a real danger that the people of Cambodia would raise against the current regime and form part of the Vietminh movement lead by the Communists.“

The interview had its intended effect and negotiations began in Paris.

Military: With French forces in Cambodia withdrawn, the fight against the Viet Minh could be stepped up. With the Issaraks given their primary demand (independence), it was hoped that they could be persuaded to bring their forces over to the government side and support the army in the fight against the Viet Minh inside Cambodia- this tactic did have some success.

In what could also be seen as another bluff, the King called on his people to mobilize in June 1953. Between 200-400 thousand men and women answered and rallied in Battambang for ‘military training’.

The French General Pierre de Langlade, who had been a good friend of Sihanouk, wrote in 1953 that he “despised this country and its people.” And was more than willing to pull the troops out.

August 1953: France agreed to cede control over judicial and interior affairs to Cambodia.

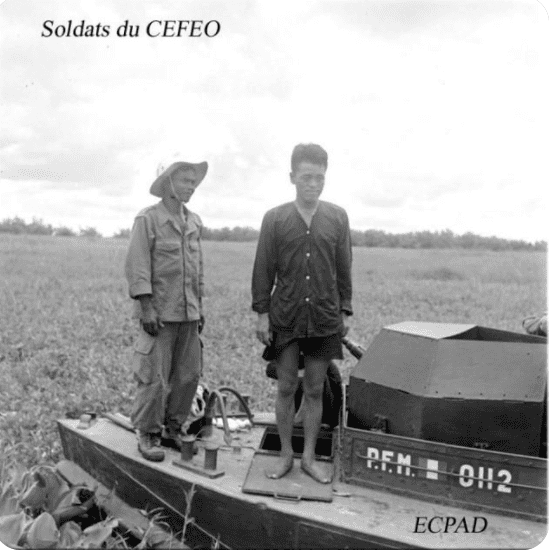

October 9-11, 1953: One week before handing over defense matters to Cambodia, Operation Seine was launched. North African colonial troops, along with Indochinese under French command made a sweep against Viet Minh and Khmer Communists from the Be River around 100km north of Saigon to the Mekong around Kratie to the northwest.

So Phim and Acha Hem Chieu’s fighters had merged into four large mobile units and together with the Viet Minh launched attacks on district guard posts in Prey Veng and Svay Rieng provinces, further aided by Tou Samuth and Keo Mony operating from the marshland on the Vietnamese border and the ‘Eastern Zone’.

Independence

October 17, 1953: France handed over military forces to Cambodia- the nation was now all but fully independent, and waited for Sihanouk to return to Phnom Penh.

November 7, 1953: Sihanouk declared Cambodian independence in Phnom Penh.

By the end of 1953 Issarak groups under Puth Chhay, Seap, Ouch Nilpich and Oum had crossed over to the government side and were integrated into the new Cambodian army Forces armées royales khmères (FARK), as had been hoped.

The non-communist Issaraks; Prince Norodom Chantaraingsey’s group, and those under command of Son Ngoc Thanh, which included Kao Tak, Duong Chhoun, Duongchan Sarath were not immediately accepted. Son Ngoc Minh’s ‘Khmer Viet Minh’, which included Tou Samouth and Sieu Heng continued to fight.

December 17-30, 1953: French aircraft out of Saigon launched bombing raids against Viet Minh in Battambang Province codenamed Operation Samaki.

The Road To Geneva

Early 1954: Bou Horng, the government’s chief negotiator, met with Savang Vong and Prince Chantaraingsey to discuss the re-integration of their fighters into the FARK. One of the deals was to allow each group to become a “battalion” in the national army. Chantaraingsey still had thousands of troops under his command, but the government only officially agreed to re-integrate about 1000 of them. King Sihanouk offered to award Chantaraingsey the military rank of a major and two of his other colleagues were to be appointed as captains in the national army. Prince Chantaraingsey agreed unconditionally with the offer, despite its drawbacks.

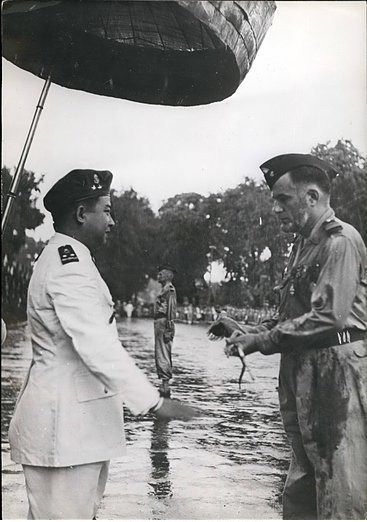

February 1954: An official re-integration ceremony was held at Chantaraingsey’s military base near Chbar Morn district in Kampong Speu province. The government provided military uniforms to each of the Prince’s 1000 fighters, yet the numbers officially re-integrated into the national army was only 300. In a show of solidarity, it was claimed that those on the government payroll shared their salary with former rebel comrades.

As promised in the initial negotiations, Prince Chantaraingsey was appointed as a major, Him Khan and Chan Tor Tress were appointed as captains, Sok Seng Roeung Moni was appointed as a two-striped officer (Sak Pi) and Ny Vanthy as a one-striped officer (Sak Muoy). This unit was named a “Third Mobile Autonomous Battalion”, coming after Savang Vong’s “Second battalion” which had been re-integrated in the same day.

At the same time, Song Ngoc Thanh sent Ea Sichau to negotiate with the government, but most likely due to the long animosity between the rebel and the king, the talks failed and Thanh reportedly fled to Bangkok.

The right-wing Issarak movement appeared depleted almost to non-existence, but Son Ngoc Thanh was not yet defeated. The communist group- numbering between 3-5000 fighters continued the fight alongside the Viet Minh.

April 3, 1954: Several Viet Minh battalions crossed the border into Cambodia and fought with FARK troops who failed to dislodge them. In part, the communists were attempting to strengthen their bargaining position at the Geneva Conference that had been scheduled to begin in late April.

April, 1954: Thanhist forces laid a brief siege on the border town of Pailin. A CIA report numbered the number of non-communist rebels in the low hundreds.

April 26 to July 20, 1954: The Geneva Conference intended to settle outstanding issues resulting from the Korean War and the war in Indochina were held. The first weeks discussed Korea, while the French and Viet Minh were still fighting the decisive battle at Dien Bien Phu.

May 8, 1953: After the siege of Dien Bien Phu ended with humiliating defeat for the French forces a day earlier, Viet Minh Vice President Pham Van Dong made a speech at Geneva demanding that both the Khmer Issarak (now comprising solely of communists and the Khmer Resistance Government- proclaimed by Son Ngoc Minh in January 1952) and the Pathet Laos be allowed seats at the negotiating table as they “represent struggle of those peoples for independence from foreign imperialism”.

Sam Sary asked for the floor saying he had not intended speak so soon but felt he must reject the Viet Minh proposal. In a rebuttal, he stated that Cambodia was at peace until the Viet Minh invasion of April 3, 1954- so any so-called government (meaning the Issaraks) must have been created only for the purpose of influencing the Geneva conference. He stressed that Royal Cambodian Government had “complete control” of the country except for “minor shifting pockets of invaders”. He said remaining dissidents were mostly foreign invaders and asking them represent Cambodia was like asking “a Polish national to represent the Soviet Union”. Finally, he pointed out the Khmer Issarak were actually nationalist rebels who had now rallied to King, and those now using that name were foreign Communist invaders.

Chinese Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai intervened, again calling for acceptance of the Soviet proposal for five-power talks based on Viet Minh proposal. The Viet Minh followed with additional peroration denying Pathet Lao and Khmer Issarak were “ghosts” and calling also for acceptance Soviet proposal for five-power talks on invitation problem.

These calls were ultimately rejected and the talks proceeded. (If anyone else enjoys reading fairly dull diplomatic reports (like the author), here’s a good start)

July 21, 1954: The Geneva Accords were signed. Cambodia was considered a neutral soveriegn, and all Viet Minh were given a 90 day deadline to withdraw, which- thanks to Chinese and Soviet influence- they did, taking many Khmer Communists with them to Hanoi. These included Son Ngoc Minh and around 1,000 others.

July 1954: Under amnesty, Son Ngoc Thanh reportedly met the King (or his aides) to plead for reintegration. Sihanouk’s message was clear, and the rebel went back into hiding.

“You would not serve His Majesty The King at the critical hour when he was accomplishing his royal mission. You have broken promises, you have openly attacked the King and his government, saying that they have done nothing but play a comedy to lull the people to sleep so that the French could oppress the Cambodians . . . If the Monarch had not obtained the independence of Cambodia, the people would have condemned him and his entourage to death, for you and your men have denounced them as traitors.”

It is more than possible that the King’s inability to forgive Thanh was political. With elections again promised, there was a chance that Thanh- still a popular figure- could have won and bring more trouble for Sihanouk.

In a bid to counter such a possibility, laws were passed that anyone who voted must have been registered at the same location for at least 3 years. As former rebels and supporters had drifted from place to place with their units- this kept them away from registration for the election.

Unresolved Issues

August 3, 1954: A US Intelligence Estimate, Post-Geneva Outlook in Indochina, stated “Non-communist dissidence appears to have abated and the principal dissident leader, Son Ngoc Thanh, no longer poses any real threat to the government. The King retains widespread popular support.”

August 11, 1954: The International Commission for Supervision and Control (ICSC-Cambodia) was established to monitor the ceasefire agreement and to supervise the disengagement of French and Cambodian military forces. ICSC-Cambodia consisted of some 500 personnel from Canada, India, and Poland. France formally agreed to recognize Cambodia’s independence on December 29, 1954. ICSC-Cambodia was withdrawn on December 31, 1969.

October 1954: Son Ngoc Thanh and his men were finally granted amnesty, but were watched closely by state security agents.

November 23, 1954: A National Intelligence Estimate “Probable Developments in South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia Through July 1956,” stated that “Son Ngoc Thanh, the last and most important of the non-Communist dissident leaders, rallied to the King….. his loyalty to the King is questionable.”

Sihanouk refused meet with Thanh, who retired to the Thai border, and began cultivate contact with intelligence operatives from Thailand, South Vietnam, and eventually the United States.

February 1955: In a final bid to reconcile with Sihanouk, Son Ngoc Thanh requested another audience with the King after again pledging his allegiance. This was denied, and, as far as is known, the two never met again.

What particularly riled the King was the support that the Indian government- not long herself free from British rule- gave to Thanh. An Indian official in the ICSC was reported to have commented that Thanh was an “ideal national leader, under whom the country could experience the kind of democracy (that India favored)”

It would appear to historians in later years that Sihanouk was not only wary of a future threat from Thanh, but was also concerned about him being remembered from his role for the cause of independence- as the king later remarked

“It is entirely wrong to pretend, as some have done… that the Conference of Geneva in July, 1954, or the ‘flight’ of Son Ngoc Thanh played a role in the acquisition of independence.”

Those who may not have approved of Thanh as such, but seen his commitment from the 1940’s and his subsequent imprisonment- followed by his few years in the jungle- would have questioned otherwise. The Democrats- the continually elected, and repeatedly dissolved in government- were also erased from the narrative, alienating many who believed that they had a part to play in ending French colonial power.

Leftist Issaraks who remained in Cambodia formed a legal political party named Krom Pracheachon, led by Non Suon, Keo Meas and Penn Yuth- all former Issaraks. It adopted the symbol of a plough.

The underground Communist Party, for which the KP was little more than a legitimate front, was led by Tou Samouth and Sieu Heng.

The Shape of Things to Come

1955 would be yet another pivotal year in modern Cambodian history- Sihanouk would soon relinquish the throne, but dominate politics. His enemies at home and abroad- real and perceived- would begin to trouble him.

Of the former right-wing Issaraks, Norodom Chantaraingsey, unhappy with broken promises from the government deal began plotting a coup. Son Ngoc Thanh was busy working with the Thai and South Vietnamese government to form a new militia- the Khmer Serei- recruiting heavily from the Khmer Krom minority across the border.

Those on the left whom didn’t attempt to join the political process also began to split. Most of the Khmer Viet Minh remained in Hanoi, respecting the official Viet Minh line of non-interference with Sihanouk while the greater ‘Liberation war’ aimed at a united Communist Vietnamese republic continued. The ‘Young Turks’- including many former AEK students from France- never really involved in the armed struggle prior to the Geneva Accords- became disenfranchised with the wider Communist movement and more acrimonious towards Hanoi, which they began to claim, had abandoned the Cambodians.

Submitted by HISTORY STEVE

All opinions are the author’s own. Any inaccuracies are unintended.