Sam Sary (1917 – 1963?) was a prominent Cambodian politician, who fell from grace after a series of scandals both at home and abroad.

Sam Sary was born on March 6, 1917 the commune of Choeun Rouk, Kampong Speu. into a family of Chinese origin. His father, Sam Nhean was a Mandarin of the Royal Palace, district chief of Kampong Trabek, province of Prey Veng, and Minister of Religion in the 1940s. Sary was the second of seven children.

Although coming from a relatively privileged family, Sam Sary grew up in a poor country. He was 12 years old when the financial crisis of 1929 broke out, which would become the crise des produits de dessert or “dessert product crisis”, where luxury products from the colonies- such as sugar and coffee- were met with a huge drop in demand and led to overproduction. This may have given him later motivation to study economics, as well as the drive for an independent Cambodia.

After his primary studies, Sam Sary entered Lycée Sisowath from 1935-1936, the Lycée Sisowath. His classmates included future Khmer Communists Ieng Sary, Rath Samoeun. In 1939, he obtained his Baccalaureate in Philosophy.

After graduation, he began his professional career in the courts: in 1940 as a trainee investigating judge in Battambang, and in 1942 Investigating Judge in Kompong Cham, in 1944 he was assigned to the Court in Phnom Penh. In the judiciary Say gained a reputation for violent methods, and was accused of beating suspects to death ‘with his bare hands’.

Sam Sary married Neang In Em- three years his senior- in 1939.

She was the first Cambodian woman to graduate (although others say that Khieu Ponnary- later the first wife of Pol Pot- received a baccalaureate first), and became principal of Norodom College in Phnom Penh.

The couple had five children, including Sam Rainsy.

After the war, in 1946, Sam Sary was sent to France to study- he was originally scheduled to leave in 1940, but World War II prevented his travel.

In France, he first stayed at the Maison d’Indochine, Boulevard Jourdan, and then as a lodger in the house of a notable French family, the de Chaisemartins, with whom he had a long friendship with.

Sam Sary later said he had little interest in the sights of Paris, and preferred to seek company and learn French etiquette and customs.

Despite a late entry into the 1946 academic year, he was encouraged and supported by many of lecturers the encouragement, but was only able to see his family on a few short visits.

He graduated on July 8, 1949 in the Public Service section at the Institute of Political Studies of Paris and was able to continue advanced administrative studies at the Faculty of Law of Paris on October 7, 1949. At the same time, he received an internship at the Bank de France and at the Academy of International Law in The Hague.

In January 1950, he obtained the Brevet du Center des Hautes Etudes Administrative offices of Paris.

Returning to Cambodia in 1950, Sam Sary quickly embarked on an ascending professional and political career. Thanks to the support of his father, he participated in politics, first with the Kanac Reastr (People’s Party) and from 1955 the Sangkum Reastr Niyum (SRN) of Norodom Sihanouk.

From July 29, 1953 to November 22, 1953, he was Minister of Education and also secretary of the Franco-Khmer commission responsible for establishing independence, where he showed impatience and a desire for total autonomy until independence was proclaimed on November 9, 1953.

In 1954, Sam Sary was chosen as personal representative of Norodom Sihanouk in the Cambodian delegation to the Geneva conference which marked the end of the French-Indochina war. He proved to be a skillful negotiator and is credited with preventing communist guerrillas from retaining control over parts of the country.

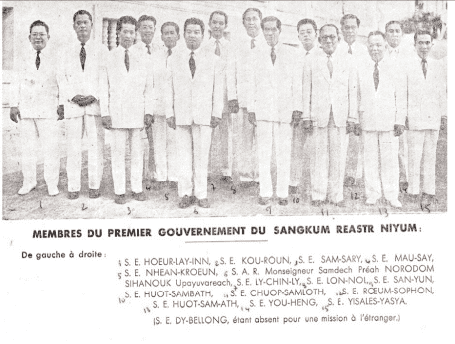

Sam Sary returned to Phnom Penh in 1955, following his success with both the independence negotiations and Geneva conference. On March 2, 1955, he was appointed, alongside Penn Nouth and Kim Tit, on the High Council of the Crown and one of the recently abdicated Sihanouk’s biographers and a leading member of the new Sangkum Reastr Niyum political movement, rising to Vice-President of the Council of Ministers and Minister of Economic and Financial Affairs, Planning and National Education.

The Sangkum, was outwardly a social movement to quell divisive political forces on both left and right, under the near-personality cult status of Sihanouk. Beneath the surface there was vote rigging, intimidation and corruption- of which Sam Sary was alleged to have been one of the chief instigators and paymaster.

In 1955, the first Miss Cambodia contest was organized. A quote from Time in 1958, described the ensuing events.

In 1955, at the first nationwide beauty contest ever staged in the remote Indo-Chinese kingdom of Cambodia, Vice Premier Sam Sary was more than an interested spectator. The judges could choose only one winner, but Sary, a suave, Paris-educated ladies’ man, picked two. In no time at all, the judges’ first choice, coffee-skinned, sarong-clad Tep Kanary, was installed in Sary’s household. Later he added Iv Eng Seng, who was only an also-ran with judges, to his collection.

In December 1955, he became secretary of the Sangkum, replacing Sim Var.

In 1956, Sam Sary traveled to the United States where, where according to some of his critics he was recruited by American secret services. Around the same, Norodom Sihanouk developed more friendly relations with Communists- especially the Chinese.

Whether it was the potential of losing more territory (Sam Sary had been critical over the ceding of Kampuchea Krom), ideological (as a staunch conservative, Sam Sary hated communism), political (Sihanouk was effectively running a one-man state) or financial (cronyism and illicit business deals were rife), the Prince and his former ally began to fall out.

According to Time Magazine (1958)

(in June 1957) powerful political enemies complained that Sary was granting profitable import licenses to the wrong people, i.e., someone other than Sary’s accusers. Tears in eyes, Sary crawled before Sihanouk on hands and knees and asked to be relieved of his job. Tears in eyes, Sihanouk let him go. In remorse, Sary shaved his head and eyebrows, entered a Buddhist monastery.

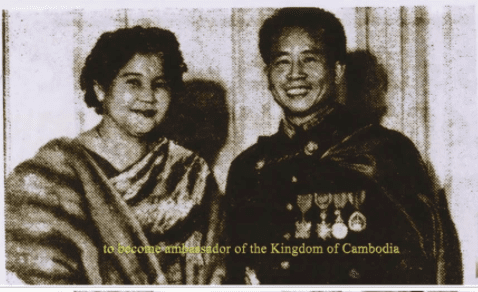

Finally, from January 1958 to June 17, 1958, he was appointed Ambassador of Cambodia to London where a soon broke in the British press.

Sary was packed off into gilded exile as Cambodia’s Ambassador to Britain. Sary’s entourage: his formidable No. 1 wife, Em, a plump suffragette, and their five children, ranging in age from 8 to 18; Tep Kanary, the young beauty queen, Sam’s No. 2 wife and No. 1 mistress; the other beauty, Iv Eng Seng, was either No. 3 wife or No. 2 mistress. To get around British sensibilities, Iv Eng Seng was listed as a governess. Whose business was it that she was also pregnant? Sam Sary called on Queen Elizabeth at Buckingham Palace and presented his credentials…..

Last month the idyllic arrangement came to an abrupt end. Iv Eng Seng fled from the embassy with her month-old baby boy to a London nursing home and complained that Sary had severely beaten her “for minor mistakes.” Nonsense, replied Ambassador Sary gallantly: “I corrected her by hitting her with a Cambodian string whip. I never hit her on the face, always across the back and the thighs—a common sort of punishment in my country.” Besides, said Sary, warming to his subject, he had every right under Cambodian law (he meant Cambodian custom) to whip the girl, because the embassy is “Cambodia in London.” Ambassador Sary got off a protest to the British Foreign Office, objecting to Iv Eng Seng’s complaints. Iv Eng Seng applied to Home Minister Richard A. (“Rab”) Butler, asking for asylum….

However, Sary’s political rivals in Phnom Penh fired back.

The government considers that the infliction of corporal punishment on a maid, which is an offense under Cambodian law, is unworthy and incompatible with the functions of a representative abroad of the Head of State.” Ambassador Sary wired back: “I maintain my protest and won’t let my country be insulted.”

The Cambodian government accused him of “grave disobedience,” ordered his recall, and issued a public explanation in Pnompenh (sic) that “Sam Sary, helped by his wife, savagely beat his pregnant concubine.” Complained Political Rival Sim Var: “Not only does he beat his concubine, but he tells the British press that this is customary in Cambodia, and now the British think we are a country of savages.”

The mistress was taken in, and married by an eccentric British barrister named John Averill—who was guided, he said, by a special vision from his Egyptian spirit, Ra-Men-Ra. Averill was an ardent member of the “School of Universal Philosophy and Healing.” whose credo was no smoking, no meat eating, and no sex. A myth has grown around the affair, claiming Iv Eng Seng was a former girlfriend of Saloth Sar, aka Pol Pot- but this seems to be no more than a rumor.

Upon his forced return, Sam Sary, in the political wilderness, began blaming his opponents- especially Sim Var- through a series of press statements and letters. Some of these directly challenged the “authoritarian and anti-parliamentarian Government”, and were dangerously close to insulting the monarchy.

Queen Kossamak called him for a meeting, expecting an apology which never came.

In an open letter dated July 4 1958, he wrote on his perceived hypocrisy around the criticism of his extra-marital liaisons “I only want to say … that it is morally preferable, if necessary, to have a concubine than to be betrayed by one’s wife or to have relations either with one’s servants, or with somebody else’s wife and her daughter, as it is the case with certain members [of the Government]….”

Two days later, Sary had a change of heart and began penning letters of apology, but it was too late, as on July 9 the High Council ejected him as a member of the Royal Council and soon lost his official Government posts.

This appears to have thrown Sam Sary in a fit of petulance, and he spent the rest of the year writing anti-Sihanouk articles in his own newspaper The Sovereign People and attempting to start a new political party- both of which failed. He was also in contact with the rebel (a name that almost always comes up in any political intrigue from 1940-75), Son Ngoc Thanh, whose Khmer Serei guerillas were fighting an armed rebellion in border provinces.

The ‘Bangkok Plot’ of early 1959 sealed Say’s fate. An attempt to assassinate Sihanouk, supposedly funded by Thai, South Vietnamese and possibly American secret services, was discovered by the Cambodians.

Sihanouk’s intelligence services discovered details of the plot and on February 21, 1959, they dispatched a battalion of troops to arrest the ringleader- the side-switching Khmer Issarak leader, turned politician, turned warlord Dap Chhuon. Chhoun was shot dead during the operation. Sihanouk took to the radio to tell the public of the plot, and although not mentioning him by name, this was enough to spook Sam Sary, who fled the country.

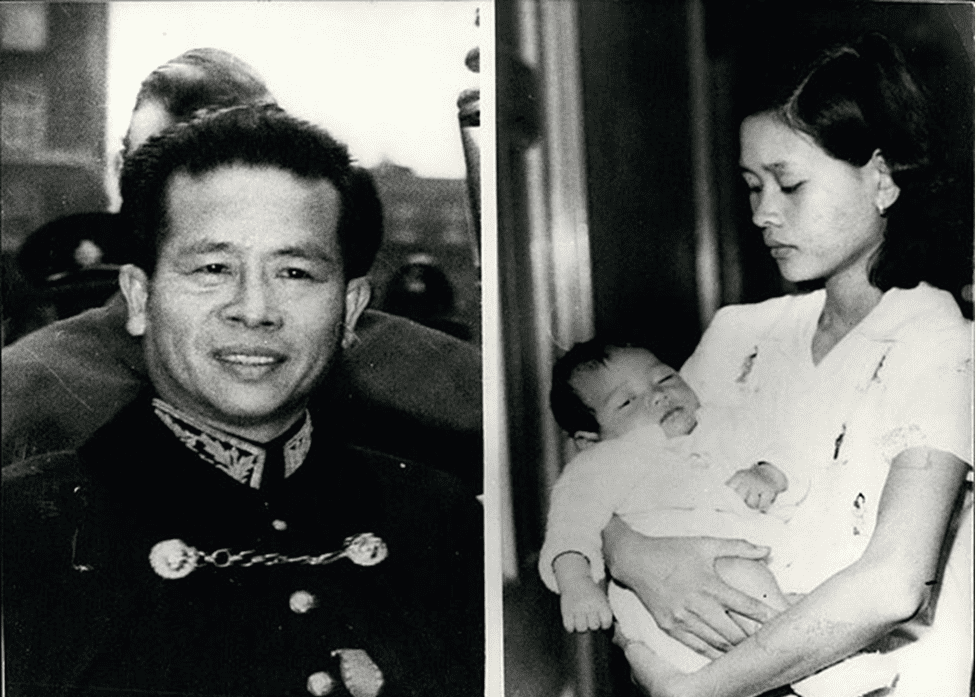

Sam Rainsy later wrote:

‘One day shortly afterwards, Sam Sary came home at about six o’clock, looking pale and in a hurry. He went to his bedroom to change, and packed a small suitcase which included a revolver. Then he prayed before one of the statues of Buddha that we had at home. He departed with (children) In Em and his second son, Emmarith. He had wanted Emmara, the eldest, to go with them, but he was out at the time.

He said nothing to the rest of us on the way out, doubtless to make the episode as unremarkable as possible, and also to protect us in the event of interrogation. I would never see him again. I was barely ten years old.

Sam Sary set off in his black Chrysler with In Em and Emmarith. I only know what happened next because of the memories of my brother. The black Chrysler crossed the Mekong via the Monivong Bridge, and went about twelve kilometers beyond Chbar Ampeuv village. There they stopped and got out of the car. Sam Sary told Emmarith, fourteen, to look after my mother, sisters, and brothers, and shook him by the hand. Then he switched to a black South Vietnamese diplomatic corps vehicle. He told our mother to drive calmly back to Phnom Penh as if nothing had happened, which she did.

The days that followed were quiet. The volunteers that had come to help with the newspaper melted away. They were replaced by civilian-clothed individuals who would repeatedly pass in front of the house. We soon noticed that we were being followed when Mother drove us to and from school. This continued for years until we left Cambodia and, after a while, came to seem strangely normal.

‘Three weeks later, the house was overrun by police searching for Sam Sary.

From exile in Bangkok, Sary wrote Sam Sary wrote a letter on April 9, 1959 to Prince Sihanouk, still complaining of his treatment:

“…. Concern spares no patriot, I know that you love the motherland. You might think I don’t like it. You went so far as to accuse me to be a traitor. Is it betraying the country to flee it to take refuge abroad? Many great men have followed this path when it comes…. you had to have the freedom to resist or the means to escape arrest…. De Gaulle, Mao Tsé Toung, Ho Chi Minh … I did not act otherwise.

On the other hand, I cannot stand the injustice of which I was a victim: you have taken the most serious sanctions, without trial, against an innocent person….Neang Iv Eng Seng can let you know herself that I was not (responsible). The English newspapers have taken revenge on the one who defended you so much against (those who) insulted you. Instead of being defended in my turn, in spite of my personal letter which I addressed to you from London, I was, on your orders:

– kidnapped from London,

– removed from the High Council,

– dismissed from the Sangkum Reastr Niyum,

– deprived of my personal effects (books, clothes for more than 7 months)

– deprived of my (proper) treatment until now”

The Prince, at the time, was in no mood for forgiveness. Sam Sary was known be moving between Thailand and South Vietnam, but had disappeared in late 1962.

His family believe he was shot in the back near Pakse in Laos under orders from Son Ngoc Thanh, who was afraid that reconciliation between Sary and Sihanouk would fracture the Khmer Serei rebel movement. Others say the Thais had him driven to Laos on the promise of setting up a meeting with Sihanouk before he was shot by his driver. His body has never been recovered.

40 years later, King Norodom Sihanouk appeared to absolve Sam Sary of his label as a traitor. A letter made public, dated April 26, 2003, read

“I have a duty to say this which is in accordance with historical truth: neither I nor the SRN Government at that time accused H.E. Sam Sary of (involvement in the) attempted “Coup” against me or forced H.E. Sam Sary to “flee Cambodia”.

At that time, there was a disagreement between H.E. Sam Sary and I about an incident at the Royal Cambodian Embassy in London, an incident which was not political in nature, but which some British newspapers and magazines had “exploited” to make it a “Scandal”.

After this incident, I recalled H.E. Sam Sary (then Ambassador) to PhnômPenh. If H.E. Sam Sary subsequently decided to leave Cambodia, it was his right.

But I totally agree with Mr. Ruom Ritt (*a mysterious figure, claiming to be a schoolfriend of Sihanouk and his French dwelling ‘pen pal’) who today does full justice to H.E. Sam Sary, a great and pure patriot who had, by my side, rendered proud services to his Fatherland in these crucial years of my first Reign and the beginning of the SRN. .. “

Another letter on April 28, 2003 reaffirmed this:

“I pay tribute to the memory of H.E. Sam Sary, when the SRN had him condemned as a “great traitor to the Fatherland” and had “posters” made representing him as a “dog” etc.

I have the honor to point out that the judgment of Mr. Ruom Ritt and my own relate only to the following historical facts: the important role played by H.E. Sam Sary in the framework of the Royal Crusade for the Total Independence of Cambodia (1952-1953), in that of the International Conference at the Geneva Summit in 1954 and at the beginning of the SRN (its foundation, its principles, its ideals, its political program, its pro-People action) …

My conclusion: I have never been able to endure injustice in any form, whether it be. I must do justice to H.E. Sam Sary for all he had made for our Homeland and the SRN in the historical period of our bilateral relations… ”.

Described as a ‘bestial man’, ‘womanizer’, ‘traitor’, ‘thug’ and ‘CIA agent’ by his enemies, but a ‘patriot’. ‘democrat’ with ‘le savoir-vivre’ and ‘crusader for independence’- Sam Sary still cuts a mysterious from 20th century Cambodian history, and one whose poor choices led to the shortening of a promising career and ultimately his life.

*Note, some of the sources have been translated from Khmer to French, and then into English, so apologies if some political terms are incorrect.

Sources include: Time Magazine, KBN, Hommes et Histoire du Cambodge, Sam Rainsy, Phnom Penh Post, Library of Congress