Two years before Cambodian independence, the most important representative of Colonial France in the country was found lying dead in a pool of blood.

Jean Léon François Marie de Raymond, Commissaire de la République had been murdered during his afternoon nap- with the blame resting on his houseboy, whom was blamed as a Viet-Minh agent. It was the second such death of a high-ranking French official in 3 months, following a suicide explosion in South Vietnam which killed the Commander of the French-Indo-Chinese forces, Charles Chanson on July 31, 1951.

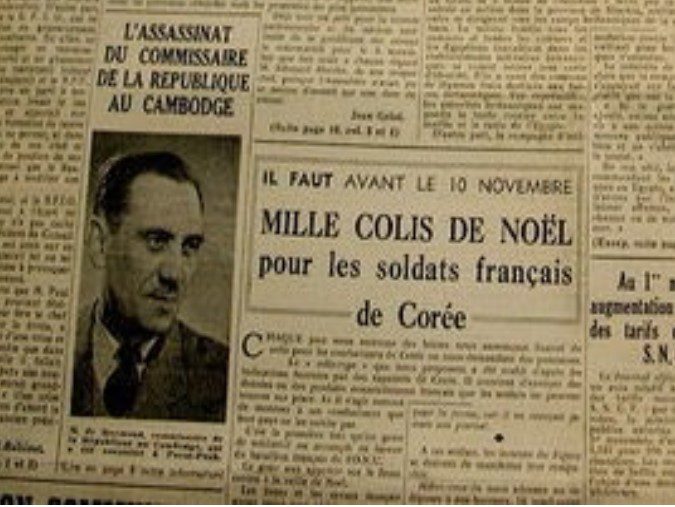

The announcement of the assassination appeared on the front page of Le Figaro October 31, 1951, accompanied by a photo of Jean de Raymond and on page 8 of the description of the facts: discovery of the bloody body on Monday October 29 at 4:10 p.m. in a room of the Palace of the Commissioner of the Republic in Phnom Penh.

Jean-Marie Garraud’s article stated: “The friendship which united M. de Raymond and the King of Cambodia, the confidence shown in him by the personalities and also the most modest inhabitants of the country prove that the mission of the representative of France has always been fulfilled with the greatest loyalty. Mr. de Raymond had by his personal action allowed pacification by obtaining the rallying of many bands of ‘Khmer-Issaraks’ rebels. His tragic death is a heavy loss for France and for Cambodia ”.

Jean Léon François Marie de Raymond

Raymond, born in 1907, had made a career in the French colonial infantry in the 1930s and was admitted to the École supérieure de guerre in 1939. However, the outbreak of year prevented the completion of his training.

He was transferred to Calcutta in mid-1945, heading up the French Diplomatic Mission with the task of re-establishing the French Colonial Ministries in Japanese-occupied Indochina. Raymond, with no experience in this region or knowledge of the situation, was a committed Gaullist, and thus preferred over more suitable ‘Vichy’ candidates- many of whom had remained in Indochina during the war.

Raymond was part of a diplomatic-military delegation that was sent to Kunming in southern China with British support. There he met Jean Sainteny- a Gaullist resistance hero in Normandy, who had parachuted into Japanese held territory with American O.S.S. officers, and troops under General Alessandri who had escaped from Indochina after the Japanese takeover in March 1945.

They planned to return to northern Indochina immediately after the collapse of Japan and to restore French rule. However, the nationalist Chinese Kuomintang and the Americans, who were still critical of the colonial mandate, prevented them, and the Viet-Minh were able to seize much of northern Vietnam in the ‘August Revolution’.

Instead, Raymond moved to Laos, first as a military advisor fighting against the Lao Issara and from April 1946-July 1947 Commissaire de la République in the Kingdom of Laos.

The Cambodian Commissioner

In February 1949, while France was fighting an increasingly bloody war in Vietnam, Raymond returned to Indochina and succeeded Lucien Vincent Loubet as Commissaire de la République in Cambodia. He quickly became friends with King Norodom Sihanouk and supported him in his efforts at autonomy, which at the time were still considered to be pro-French.

Sihanouk, during this period, favored ‘independence within a French Union’, or ‘50% independence’, as he deemed it- which was rejected out of hand by the Democratic Party held National Assembly. Raymond repeatedly accused the elected Cambodian parliament of incompetence and portrayed it as a hindrance and antithesis to the king’s patriotism (which, of course had a Francophile leaning). The king dissolved the National Assembly in September 1949.

Sihanouk, always prone to flattery, was perhaps inspired by Raymond in his distain towards parliamentary institutions, and plotted his own political aspirations following the vague wordings of the 1947 constitution, which recognized him only as the ‘spiritual head of the state’- or a constitutional monarch.

Shortly before Raymond’s death, the Democrats won a majority in the second National Assembly election of September 1951, with Huy Kanthoul becoming Prime Minister on October 13.

In the weeks proceeding the assassination, in an apparent effort to win greater popular approval, Sihanouk asked the French authorities- and therefore Raymond- to release the nationalist (and one of the most influential Cambodians of the 20th century) Son Ngoc Thanh from exile in France. Thanh, a political chameleon, had been a revolutionary newspaper editor, a Japanese styled ‘fascist’, the leader of the ‘Umbrella War’, the first civilian Prime Minister, was at the time the figurehead of the anti-French Khmer Issarak movement, and would later ally with the communists against Sihanouk, before turning a CIA asset leader of the Khmer Serei movement, an ally of Lon Nol and Prime Minister once again in 1972.

Thanh arrived in Phnom Penh to great fanfare- reports say a crowd of 100,000 were there to greet him- on the very same day that Raymond was murdered. This apparently upset Sihanouk, who perhaps underestimated the support of Thanh and made efforts to have him detained again- rejected by the Democrats. Within six months Thanh had fled to Siem Reap to continue an armed resistance against the French and the monarchy.

Death and Funeral

The official story is that Raymond was stabbed to death in his room at the palace by his Vietnamese houseboy. There were rumors that the Frenchman had a sexual penchant for younger boys- which was apparently exploited by the Viet-Minh, who subsequently hailed the alleged murderer as a hero.

Those behind the killing were swiftly sentenced to death in absentia, but no record (to the author’s knowledge) can be found of any arrests.

The funeral took place in Phnom Penh, with Le Figaro on November 1, 1951, reporting that it was held in the presence of King Norodom Sihanouk, General de Lattre de Tassigny, High Commissioner of France and Commander-in-Chief in Indochina. A telegram from Mr. Letourneau, Minister of State (in charge of relations with the Associated States) and Mr. Tran Van Huu, head of the Vietnamese government read “The name of the governor Raymond is added to the glorious list of great Frenchmen who died on the field of honor and fell in the service of a noble cause “.

Then Le Figaro of November 2 on page 9, reported the declaration of General de Lattre de Tassigny at the funeral of Mr. Jean de Raymond: “By substituting this ignoble assassination for combat that he does not dare to engage, the Vietminh admits his weakness “.

Raymond’s remains were repatriated to France, the ceremony announced in the section “Le Carnet du Jour” in Le Figaro on November 26, 1951:

“ The ceremonies scheduled for today Monday November 26 at the Invalides on the occasion of the return of Monsieur the Governor Raymond, who died for France, will take place at 3 pm instead of 2.15 pm ”.

In the Le Figaro of the following day, on page 9, a small paragraph announced ” The body of M. de Raymond has been brought back to Paris…. A military apparatus brought back yesterday to Bourget the mortal remains of Mr. Jean de Raymond, Commissioner of the French Republic in Cambodia, assassinated by the Viet-Minh. The ceremony at the Invalides took place in the presence of members of his family, Albert Sarrault, Jean Letourneau, the delegation of Cambodia and many other personalities. Interment then took place in Vannes in the family vault”.

The Aftermath

No sooner was the unfortunate Monsieur Raymond interred, events in Indochina moved at comparatively break-neck speed considering the usual pace of French bureaucracy.

Le Figaro of November 26, 1951, reported the return of General de Lattre to Paris from Hanoi to attend the meeting of the High Council of the French Union, a cordial reception in a living room decorated with French, Vietnamese, Cambodian and Laotian flags. “ The High Council will be, through the collaboration of all, the body which will make it possible to reconcile, in a practical and acceptable way for everyone, the cooperation and sovereignty of the component States”

The deliberations of the council were to be kept secret, but were really used to discuss the possible independence for Cambodian and Laotian and to find a solution for the French to remain in Vietnam.

The first session was held at the Élysée on November 30, 1951 under Vincent Auriol, President of the Republic.

On October 19, 1953, the Kingdom of Cambodia was granted full independence, although the date is now set on November 9, after Sihanouk returned to Phnom Penh. On October 22, the Kingdom of Laos was also granted full independence.

Some French historians link the now almost forgotten death of Raymond to the rise of Sihanouk as a political figure. Having lost, perhaps, the last Frenchman to have the King’s ear, the once Francophile monarch shifted his position- and not for the last time in his long life.

How much Jean Léon François Marie de Raymond, soldier, diplomat, and alleged pedophile, influenced the rapid shift in Cambodia remains to be debated. In June 1952, the King dissolved the National Assembly, ending the role of his rivals- the Democrats- much maligned by Raymond during his life in Phnom Penh.