By 1942, with much of the motherland under Nazi occupation and the rest under the collaborating Vichy government rule, the few French left in Indochina were isolated and cut off from events in Europe. In August 1941, an Imperial Japanese garrison of some 8,000 men entered Cambodia, under conditions that allowed the French to retain administrative authority.

Japan had been the mediator in negotiations to end the Franco-Thai war of October 1940 – January 28, 1941, which ended in the Cambodian northern provinces- which had been under Siamese/Thai jurisdiction from 1769-1907- returned again to Bangkok.

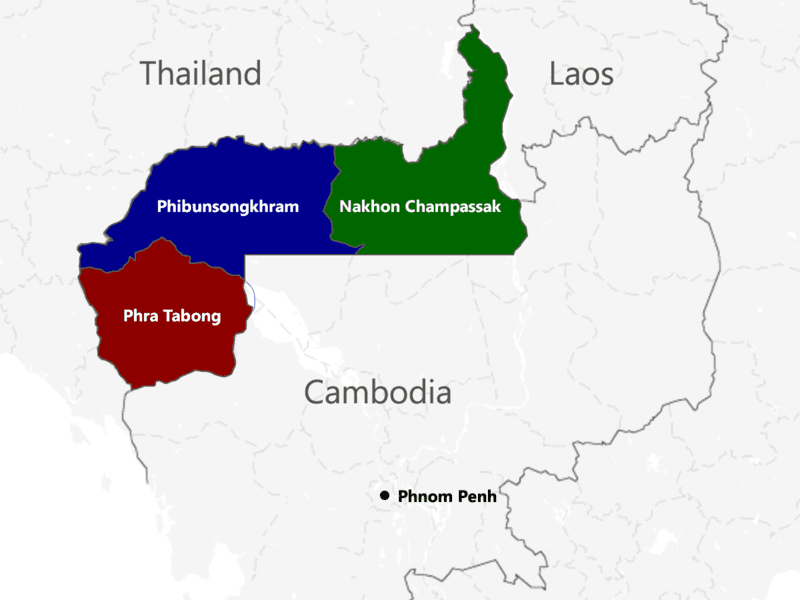

On the modern map, the territory handed over in 1941 encompassed Battambang and Pailin, which became Phra Tabong Province, Siem Reap, Banteay Meanchey and Oddar Meanchey, reorganized as Phibunsongkhram Province, Preah Vihear, which was merged with a part of Champassak Province of Laos opposite Pakse to form Nakhon Champassak Province, along with Xaignabouli, including part of Luang Prabang Province, which was renamed Lan Chang Province.

The loss of around 1/3 of Cambodian land- including the ‘rice bowl’ of Battambang and the lauded symbol of national pride- Angkor Wat- which had been relatively unknown to most before 1907 and the French led restoration- caused further anger among the growing number of Khmer nationalists.

Seeds of Revolt

On June 17, 1884, a litle over two decades of French ‘protection’ which had been relatively benign- and effective in preventing the almost continuous wars fought over Cambodia by her larger neighbors- French rule began to consilodate in Indochina. Since the death of Napoleon I in 1821 to 1880, France had engaged in over 30 wars as far apart as Crimea, Mexico, North and Sub-Saharan Africa, China, Japan and the South Pacific. The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 cost the French army around 140,000 dead, a smiliar number wounded and 100,000 taken prisoner. The French indemnity of 5 billion Francs, anywhere from $23-100 billion in today’s rates (inflation and gold prices taken into account), were paid to the German Empire.

France was going broke, and many of her less productive colonies were a further drain. Cambodia, which had promised a ‘backdoor to China’ up the Mekong (later proved unavigable) was one such far-flung corner of the empire.

French influence had, up until the last quarter of the 19th century, little effect on most aspects of Cambodian lives- with the exception of the nobility and wealthier groups. A series of rebellions against King Norodom, headed by his anti-European (and very anti-Norodom half-brother Prince Si Votha), had required French assistance in 1877 and again in 1885, and tested both the pockets and patience of the colonialists. Cambodia had to start giving something back. Inevitably this led to national reforms including land, education and the obvious money spinner- taxation.

The harsh practices under Governor Charles Antoine Françis Thomson led to more dissatisfaction, and another rebellion- which caused the deaths of up to 20% of the Cambodian population died from 1884-87. Around the same time a secretive end-of-the-world millenialist Buddhist cult began to spread in southern Cambodia and Cochinchina (southern Vietnam).

After the brutality of the revolt (more of a war for control of the crown than independence) colonial control waned until the death of Norodom, and his more co-operative half-brother Sisowath was, under more than a little treachery towards the House of Norodom, brought to the throne.

This co-incided with the middle period of the French Third Republic- a time of progression and modernisation in Paris which was quickly spread to the empire. These reforms began to effect the very fabric of traditional Cambodian society- especially the guardians- the Buddhist clergy. World War I would, however bring more economic woes.

The Modernist Mohanikay

Together with a growing educated middle-class, dissadent monks headed public protests in 1916 and 1925, partly inspired by rebellious religious leaders known as neak mean bon (meritorious people). In response to this, the French authorities founded The Buddhist Institute as a means to keep the Sangha out of politics. The plans for a non-interfering clergy failed, and the Institute soon became the epicenter of the new nationalist movement.

Cambodian Buddhism was not a singular force. Aside from a few mystic-cultist monks in the countryside, the conservative Thomayut sect favored by Bangkok still held influence in the Northwest, while the modernist Mohanikay sect, preferred by the French was promoted by the Institute.

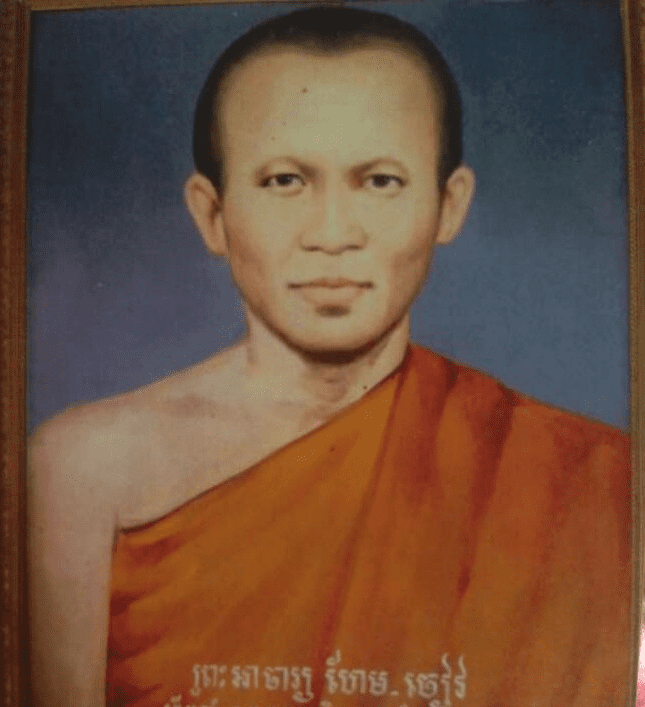

One such monk of the modernist school, named Hem Chieu, began translating and editing Buddhist texts with stark nationalist undertones. In 1929, King Monivong passed a law- Kret 77– that any new Buddhist texts would first need approval of the Ministry of Interior, followed by the Council of Ministers and finally the monarch himself. This pushed many modernists underground.

Other modern ideas also backfired on the French. The first printing press arrived in around 1886- in Latin script only- much to the dismay of the conservative clergy- who wished to keep the traditional handwritten scrolls called sastras.

The Free Press

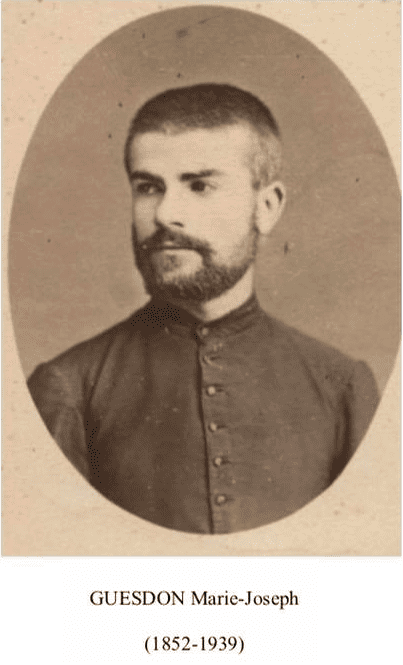

A French Jesuit priest by the name of Marie-Joseph Guesdon arrived in Cambodia in 1874, where he cultivated an interest in the country and its language. On his return to Paris in 1894, Guesdon cast his own Khmer typefaces and collaborated with French publishing house Plon-Nourrit to release books in Khmer. Parisian foundry Deberny & Cie further developed Khmer font types which were later supplied to major printers of Cambodian works, such as the Imprimerie du Protectorat, Plon-Nourrit and F.H. Schneider, and used in a wide array of publications from the turn of the 20th century.

As the printed word slowly began to circulate, a new breed of French-educated Khmer intellectuals began to grow. In 1911, the first official gazette in the Khmer script, Reachekech (Royal Gazette), commenced publication, followed by the first Khmer script newspaper La Gazette Khmer in 1918.

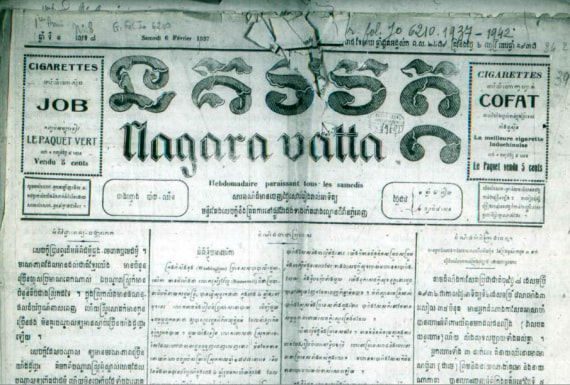

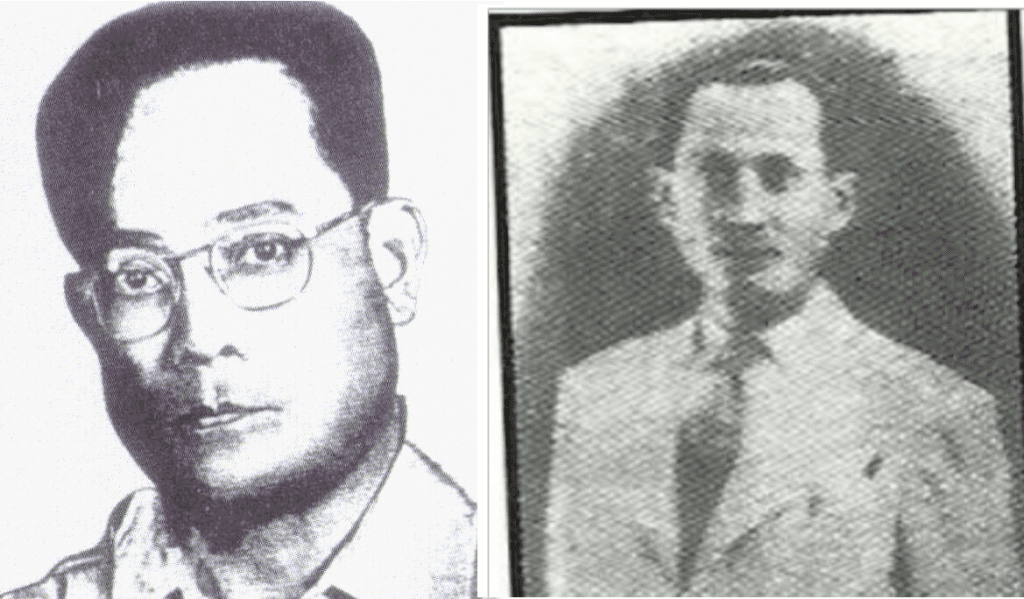

Arguably the first newspaper to hold national appeal was Nagaravatta (Angkor Wat), published from 1936 by Pach Chhoeun, Sim Var (Prime Minister in 1958) and two-times Prime Minister Son Ngoc Thanh. Pach Chhoeun and Son Ngoc Thanh also worked within the Buddhist Institute and allied themselves with important monks, such as Hem Chieu.

Opinion pieces on matters of politics and self-improvement were published under pseudonyms- an editorial policy still carried out by lofty publications such as Fresh News and Khmer Times- and proved popular among the educated classes and the countryside illiterates, who would have articles read to them by monks.

Although not outwardly seditious, and no doubt tame by today’s standards, Nagaravatta drew ire from the French administration and the Khmer elite.

A Renseignements généraux report, dated December 9, 1941, forewarned:

“There are many indications that the movement is unstoppable when we see the enthusiastic demonstrations of sympathy during the meetings and banquets. We believe it would be dangerous to rely too much on the shyness and the gentleness of the Cambodian temperament prone to sudden and violent reactions, and we may fear serious trouble in the near future if no change is brought to their social status by the administration.

Let us note that the renovation movement even affects the monks, and their going over to a group that operates within the traditional framework of Buddhism is of paramount importance. Let us not forget, that in case of an uprising or any kind of demonstration, the bonzes can muster the masses within a few hours.”

The Plot

The Japanese military occupation split the country. There were many, including Son Ngoc Thanh who took to the Japanese notion of Pan-Asianism– the liberation of Asia from European hegemony. Others- including the large Chinese diaspora community who had at least some knowledge of Japanese atrocities committed to the north- were fearful of a new superpower, far more brutal than the French ever were. The French and Cambodian elite, having lost the Northwestern provinces to Thailand were no doubt in fear that their tenuous position across all Indochina could be toppled at any moment.

Son Ngoc Thanh used the confusion to his advantage, traveling the country to speak about the new dawn of Khmer nationalism. He was joined the a prominent monk Achar Hem Chieu, now a professor at the Higher School of Pali in Phnom Penh, who strongly objected- among other things- to attempts by the French to Romanize the Khmer writing system.

Others, including Bunchan Mul and Nuon Duong were recruited as organizers, and to spy on French military strength, including French-controlled Khmer militia forces. Son Ngoc Thanh approached the Japanese for protection in case of French retaliation, which was quietly granted- providing the Khmers did not resort to violence.

However, there were opposing factions within the movement, and plenty of spies who related the activities of Son Ngoc Thanh and Hem Chieu back to the French authorities, who were beginning to worry that the Japanese might step in to overthrow them.

The Arrests

On July 12, 1942, Nhem Phuong, a soldier from the army transport corps, overheard a conversation between other soldiers in the barracks and a declaration from a fellow militiaman named Srey Tum that almost all the soldiers of his corps were about to rebel against the French, with the aid of the Japanese. Prince Sisowath Monireth (overruled for the throne in 1941 despite his higher status, for his cousin, the 19 year old Norodom Sihanouk) was said to be at the head of the planned uprising. That evening he reported the conversation to his neighbor, in the Catholic village where he lived- Prince Norodom Rassapong.

The prince relayed this to French authorities the next day- leading to a police investigation and Achar Hem Chieu’s and Nuon Duong’s arrest four days later, on the 17″.

The arrests antagonized the Buddhist sangha and lay people- as, against Buddhist law, Hem Chieu was defrocked by the state and not first by a council of fellow monks.

Seemingly expecting trouble, Hem Chieu left a manifesto, which was discovered in his cell following his arrest- reactionary, even by today’s standards, and worthy of imprisonment under current laws:

What we must do to protest as strongly as we can is summarized as follows:

1—On the day when the head monk (Athikar) in the monastery (Vihear) convenes all the monks to read out the new regulations that concern us, we must all be present. After the reading we must state all together that we shall refuse to comply with those rules, as we are only guided by the regulations described in the Tripitaka. They alone are able to render men devoted and loyal to their country. We shall demand the immediate withdrawal of Kret 77.

2—The most important thing is that each of us must sign [a petition]. We [thereby] protest as strongly as we can to demand that we behave according to Buddhist precepts.

3—If we refuse to comply with those new decisions, it is likely one of the monks will be arrested, defrocked and condemned.

4—If one of us is arrested, we must spread the news, with the utmost urgency, to all the pagodas, to come and protest in front of the relevant authorities. Those who do not come must be punished.

5—In that case, let us show solidarity and declare we shall not let a monk be condemned. But while you demonstrate it is absolutely forbidden to carry any kind of weapon.

6—Under such circumstances, it is likely the militiamen will block our way. We shall then show them our bare hands and say that we are not waging war, but simply protest.

7—If we are asked the name of the leader of this demonstration, we shall all put up our arms, claiming that it is all of us. We shall explain too that the ringleaders are the Buddhist precepts that are the fundamental basis for our action.

8—If we are asked the purpose of our protest, we must reply that we ask for the withdrawal of the Royal Ordinances [KRET-71] that have undermined the prestige and the smooth running of our canonical rules.

9—If people claim we want to institute a new set of religious beliefs, different from the Mohanikay and the Thomayut sects, they must understand once for all that the monks who strive to study the Buddhist precepts are the purest monks, but not the advocates of any new religion.

10 — We must wait for the repeated ring of the alarm bells (tocsin) that will sound the beginning of the demonstration. In this way we shall be able to communicate the news to all the monks in all the pagodas, even during the night.

11 — Monks must say their prayers while overturning their bowls, instead of going to beg for food. Those who continue to beg round peoples homes are not monks who abide by the Buddhist regulations.

12 – Novices must, on that occasion, put on their robes like the monks.

13 — This King is not Buddhist.

14 — We shall refuse to take part in the “Rathen” ceremony organized by the King at the end of lent [vossa, the rainy season]

15 — We must consider the King unreasonable. We must have nothing to do with him.

16 — We shall beg the Administration not to quarrel with the Higher School of Pali or the Royal Library.

[signed] Hem Chieu

Hem Chieu and Nuon Duong were accused by the French authorities of:

1 – Making anti-French remarks;

2 – Regretting the loss of Battambang and Siem Reap;

3 – Lamenting the rise in the cost of living due to the war and Japanese occupation;

4 – Planning an uprising to put an end to the tutelage of France and the Vichy regime;

5 – Secretly negotiating with the Japanese occupation forces;

6 – Plotting a rebellion with the Cambodian military; organizing secret meetings to promote that rebellion;

7 – Using witchcraft to make Cambodian troops invincible

The Umbrella War

Son Ngoc Thanh took refuge in the Japanese military headquarters to avoid his own arrest and began organizing a demonstration- with tacit support from the Japanese- calling for the release of the detained monk.

On July 19, an announcement was given to the public:

Tomorrow morning all demonstrators, monks and lay people, must eat before 6 a.m., then walk to meet together … behind the western entrance to the palace. … they must parade peacefully, i.e. empty-handed and with no weapons, in an orderly, quiet fashion, without talking, with a banner up the front saying: ‘We are calling for the release of Achar Hem Chieu and Nuon Duong’. The parade should then stop in front of the office of the Resident-Superior. If the police chase or hit them, they must resist passively, not fight back or do anything; they must stay calm. … The Japanese can intervene or contact the French government only if the demonstrators follow these steps as ordered.

The following morning as many as 3,000 gathered, including around 500 monks from all the major wats in Phnom Penh. The monks carried their parasols- hence the name ‘Umbrella War’. A Japanese plane circled overhead- taken as a sign of support from the crowd, led by Pach Chhoeun.

“On the 20 July 1942 at 6 a.m., after meeting at the agreed place, the demonstrators, monks and lay people, so many of them that they were all over Phnom Penh, paraded from that place to the office of the Resident-Superior. … with Pach Chhoeun as leader, courageously striding in front. The demonstrators paraded bravely with no illusions. French, Khmer and Vietnamese spies walked alongside….”

An interesting footnote is, according to Dr. Henri Locard, Prince Monireth- elder son of King Monivong- had been spotted talking with Pach Chhoeun as the demonstrators marched in front of his residence at 33 Boulevard Doudart de Lagree (now Norodom Boulevard). Soon after, the one-time heir to the throne was enrolled into the Légion étrangère.

Pach Chhoeun led the march to the offices of the resident supérieur – a Monsieur Jean De Lens- where he met with French officials and demanded the release of the jailed monks.

The crowd surged forward to protect Pach Chhoeun, but inadvertently pushed him inside the compound. The French then locked the gates and arrested the march leader. This inflamed the crowd and a riot soon broke. French and Khmer soldiers were beaten with sticks, and the monks’ umbrellas and pelted with stones and kuan tang (a metal rivet attached to an elastic lead). There were injuries on both sides as police fought to regain order. As the riot began to intensify, two truck-loads of Japanese soldiers arrived. The soldiers stood back and did not intervene.

Police then began arresting demonstrators as they fled. Chief organizers including Nuon Duong, Bunchan Mul, and Pach Chhoeun were swiftly imprisoned. The French closed the Pali language school in Phnom Penh, along with the offices of Nagaravatta.

The Aftermath

On December 19, 1942, Hem Chieu was put before a French military tribunal in Saigon, where he was sentenced to death, later commuted to life imprisonment with hard labor. He was sent to the prison for political dissidents on the island of Poulo Condore off the coast of southern Vietnam, where he died from an illness, in October 1943, aged 46. His named lived on after the United Issarak Front- a guerrilla movement which would eventually morph into the Khmer Rouge- formed an Achar Hem Chieu Unit, under So Phim (later the commander of the Eastern Zone, who shot himself in 1978 after being accused of treason by Pol Pot). The monk is now considered as a martyr and hero by many, and his image has seen held in various contemporary protests.

Around 25 prominent nationalist leaders were arrested in the demonstration, with many later released by the Japanese in 1945, including Nuon Duong, Bunchan Mul, and Pach Chhoeun.

Son Ngoc Thanh fled to Bangkok, from where he went into exile in Japan. He returned to Phnom Penh in March 1945, after the Japanese seized control from the French. He was first made Foreign Minister, and following the surrender of Japan, Thanh appointed himself Prime Minister. With the restoration of French control in October, he was arrested, and sent into exile first in Saigon and then in France. Thanh would live to fight another day, heading rebel armies in the Northwest, and returning to office under the Khmer Republic.

Although the Umbrella War failed- both in its aims to release the imprisoned monks and any major overhaul of the colonial regime- it was the first major organized effort of the independence movement and considered an important milestone in Khmer nationalism.

By History Steve. *The views expressed are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those of CNE

Sources: Christopher Baker Evens, Micheal Vickery, Ben Kiernan, Dr. Henri Locard, Sous-Dossier B of the Le Blanc Archives, France.

I lived in Cambodia 2002–2017 and have read books about the History of Cambodia. I knew that the Thai had occupied Western Cambodia during WWII and that there was a Japanese military occupation in 1945. I didn’t know any of the details. This article is really great in explaining in detail about what was going on in Cambodia up to and during WWII.