The Jarai people are an ethnic group whose traditional homeland were the Central Highlands of Vietnam and Northeast Cambodia.

Their language is related to Chamic, which is in the Malayo-Polynesian language family, but has been influenced over the centuries by the neighboring Mon-Khmer language. It is likely that the Jarai ancestors, like other smaller hilltribes collectively referred to a Degar or Montagnard, were pushed into the remote mountains and jungles as the early Mon-Khmer and Cham kingdoms began to expand.

Although isolated, there was contact with the Khmer kings and the Viet Lords of Hue, who revered the mystical shamans of the Jarai- known as the Kings of Fire, Water and Air/Wind.

Early Vietnamese accounts talk of Thủy Xá and Hỏa Xá (“Water Haven” and “Fire Haven”) – two former Jarai areas located in Central Highlands of Vietnam. The ‘kings’ were certainly famous enough in the region, and named in several local languages: “King of Water” (Jarai: Pơtao Ia; Rade: Mtao Êa; Vietnamese: Thủy Vương; Khmer: Sdet Tik; Laotian: Sadet nam), “King of Fire” (Jarai: Pơtao Apui; Rade: Mtao Pui; Vietnamese: Hỏa Vương; Khmer: Sdet Phlong; Laotian: Sadet Fai) and the lesser-known “King of Wind (or Air)” (Jarai: Pơtao Angin).

According to legend, King of Water could pray for rain and bring floods, while the King of Fire could pray for hot weather, bringing droughts and summon lightning. French anthropologist Jacques Dournes, who lived in Vietnam for twenty-five years from 1946 to 1970, studied the culture of the Jarai and other highland ethnic groups.

Describing the Jarai ‘wizards’ in his work ‘Pötao, une théorie de pouvoir chez les Indochinois jörai’ he noted “They lived far from each other, were never to meet, under pain of precipitating nameless calamities on the country… Their authority was purely mystical; (they) never encountered temporal power ”.

The European Interest

In 1666 a Father Giovanni Filippo Marini, a Genoese Jesuit, published an account of his travels through Tonkin and Laos- ‘A New and Curious Account of the Kingdoms of Tonquin and Laos’.

When describing the leadership structure of Tonkin, he wrote “One counts five princes who are sovereigns and if one wants to include certain people who live in the more remote and wild mountains and who follow two small Reys called the Rey of Water and Rey of Fire, then there would be seven…… the sixth and seventh are found in the Rumoi, where the savages live, and some of them obey the two little Reys of Fire and Water as I have noted above.”

By the mid-nineteenth century, the French colonial adventure in Indochina was in full swing. It was an age of science and discovery, and colonial authorities- and amateur European historians and ethnographers- were trying to map, categorize and understand their new colonies- from the pyramids of Giza, the ruins of Babylon, the mysteries of India to the wonderous abandoned city of Angkor.

Another priest- Frenchman Father Charles-Emile Bouillevaux- in 1858 published “Voyage dans l’indochine 1848 – 1856 ” after visiting Angkor and northern Cambodia.

An interesting footnote is that his writing style was not exactly endearing to the average reader, and the book gained little attention in France. Some sources say that some years later, the French representative (if true, likely the illustriously named Ernest Marc Louis de Gonzague Doudart de Lagrée) advised the priest to quietly forget about his ‘discovery’ of Angkor Wat, and allow the credit to go to the more eloquent (and deceased) Henri Mouhot who followed in Bouillevaux’s footsteps.

In 1851, Bouillevaux reached northeastern Cambodia- a wild land of the “Penongs” (probably referring the the Phnong/Bunong tribe- relations of the lowland Mon-Khmer. He was told that among the Jarai people who lived to the north there was a man called the King of Fire and Water – not a monarch, but a respected shaman and the keeper of a sacred sword and other objects which had magical powers. This sword was linked to the Preah Khan– Royal Sword- of the Khmer kings, while other tradition says it fell from heaven to grant power to the Jarai people.

He learned that kings of both Cambodia and Emperors of Cochinchina sent gifts to the King of Fire and Water every three years. Later it was discovered that this was not a single entity, but three, including the lesser-known King of Wind.

The legends were investigated more thoroughly by subsequent French scholars who were arriving by the late 19th century.

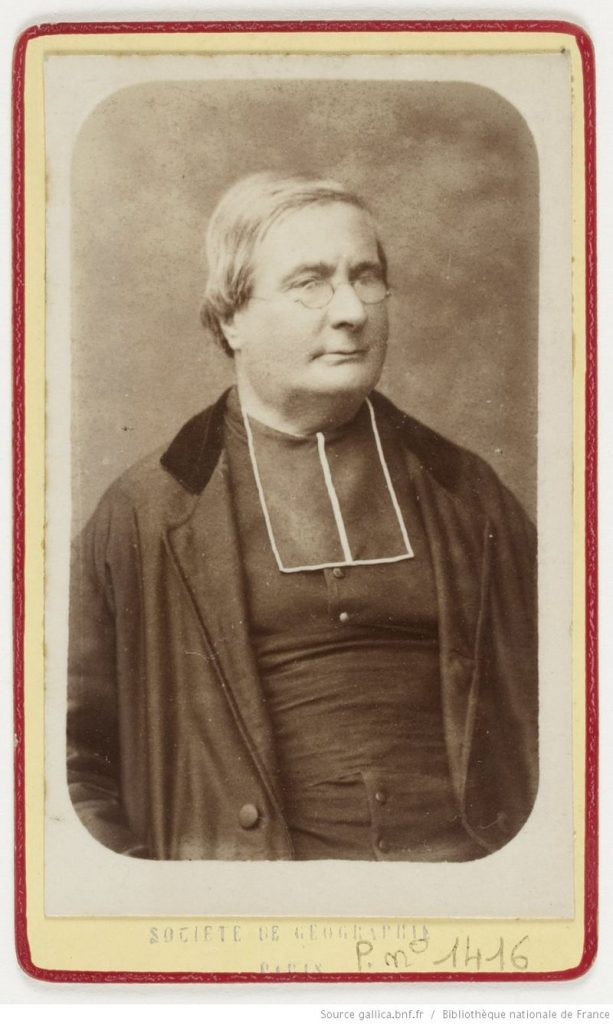

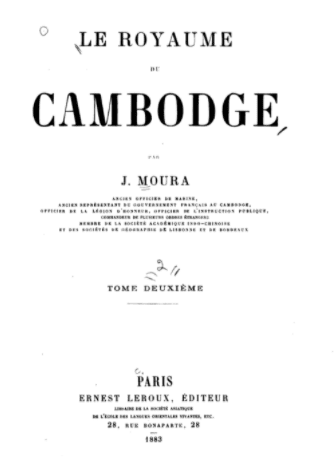

Jean Moura, author of Le royaume du Cambodge (1883) was among them- although he never made it to the Jarai lands, or came across anyone who had- the lowland Khmer had a fear of a killer forest fever that afflicted those who ventured into the jungles. Nevertheless, he recording tales of how the King of Fire possessed a sacred sword or sabre, while the King of Water held a liana branch- also reported as a rattan whip- ‘which had been cut centuries before, but remained alive and green’. He noted that the shamans appeared to come from among the regular good peasants, and held no political powers- but were venerated and highly respected, not only by the Jarai tribes, but by other entities across Indochina.

On the occasion of marriages and rituals honoring the spirits, the people would summon the King of Fire. A special place was prepared for him, white cloth was placed on the ground, and his path was strewn with ribbons of cloth. The faithful would press behind him, holding the train of his loincloth and shouting with joy. When the Kings of Fire and Water appeared in public, everyone must bow, for if this homage was not rendered, terrible storms would ensue.

He also noted the powers attributed to the talismans, and wrote that the kings of Siam and Cambodia as well as a Cambodian rebel named Pu Kombo, had all, at some time attempted to capture the sacred sword, but all had failed, due to the spirit that lived within the blade. The sword, Moura said, was kept wrapped in silk and a layer of cotton cloth.

Captain Cuped’s Map

In 1887, a 28-year old French army captain, Pierre-Paul Cupet (1859–1907) joined a group of military officers and civil servants led by Auguste Pavie- France’s vice-consul in Luang Prabang- who were carrying out extensive exploration and mapping of the small principalities between Vietnam and Siam, in modern-day Laos. The following account is taken from Harold E Meinheit’s Captain Cupet and the King of Fire: Mapping and Minorites in Vietnam’s Central Highlands.

Cupet had received warning that there might be opposition to his surveying mission. As Cupet tells the story, on December 9 he was sitting on a tree stump near Stung Treng, when a Lao medical practitioner approached him. Having just returned from the Central Highlands, the Laotian told Cupet he would need the approval of the “Sadet,” if he wished to travel in the Highlands. A gift of one or two elephants would be necessary to gain the Sadet’s approval. To Cupet’s expression of shock at the enormity of the gift, the Laotian replied that the Sadet “is the king of all the savages.” The “Sadet” or “Sadet Fai,” Cupet later learned, was the Laotian name for the King of Fire.

Cupet left Kratie on January 22, 1891, along with ten Cambodian militiamen, six elephants, and baggage carts drawn by oxen. In early February, Cupet reached the village of Ban Don, located on an island in the middle of the Srepok River which had been established by Laotians in the mid-19th century- and a well-known center for the trade in elephants. Elders told Cupet they could remember Cambodian caravans in the distant past passing through the village on their way to the Kings of Water and Fire, “potentates of a sort, half-chiefs, half-sorcerers.” Cupet was warned that he must gain the kings’ protection if he intended to proceed into the Highlands.

Proceed he did, and 93 kilometers from Ban Don, Cupet reached the Jarai village of Ban Khasom. He was informed that the King of Fire had arrived in the village the previous evening and was willing to receive him.

Inside a longhouse filled with villagers, Cupet- likely the first westerner to encounter the King of Fire- saw him perched on a bamboo platform with nothing to set him apart from the other highlanders. He sat smoking a long copper pipe “like any other mortal.” In response to a signal from the King, a large gong was sounded and Cupet was asked to make an offering to the spirits and drink from the communal rice wine jar.

Cupet presented ten iron ingots for the alcohol and a piece of red cloth for a chicken, and the King of Fire offered an invocation and Cupet proceeded to drink from the jar with a long bamboo tube.

Some of the King’s followers challenged Cupet, pointing to bad omens portending his arrival. They complained that he had not brought expensive gifts and voiced suspicions that Cupet had come to steal the King’s sacred saber.

Cupet responded that his talismans were more powerful than those of the Kings of Fire and Water and produced his compass. The moving needle and especially the glass, which none of those assembled had ever seen before and which blocked their efforts to touch the needle, duly impressed the assemblage.

The meeting concluded with the King giving Cupet a brass bracelet and a small quantity of rice. The King explained that the bracelet would be a sign to the highlanders that Cupet was a friend of the King. If a village refused to provide aid to Cupet, he was to throw some of the rice on the ground, invoking the King’s name, and the soil would become infertile.

Cupet soon learned that a rival Siamese military expedition (Siam was trying to gain territory in Laos and Cambodia to counter French advances) of some 400 men was headed towards Ban Don.

On the way to face them, he passed through the village of the King of Water and exchanged gifts through an intermediary. The King of Water offered friendship with the traditional gift of a brass bracelet and provided guides and porters for the march.

Arriving in Ban Don on March 22, Cupet entered the camp of Luang Sakhon, the commander of the joint Siamese-Laotian force, and told him that he had already gained the support of the highlanders, who not want to fall under Siamese rule. Showing Luang Sakhon his two brass bracelets, Cupet told him that he had an alliance with the Kings of Fire and Water. After some time to think, Luang Sakhon ordered his troops to withdraw. Cupet and four Cambodian militiamen were successful in turning back a Siamese invasion of the Central Highlands, boosting his (and France’s) prestige among the highlanders.

20th Century Meetings

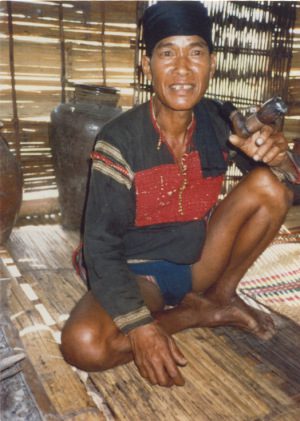

Gerald Cannon Hickey- an American ethnographer- was invited to a ritual with one of the last Kings of Fire in 1966 (cover photo left). He wrote:

Ksor Wol, an assistant to the King of Fire, said the present king was Oi Anhot (grandfather of Anhot) of the Siu clan from which all of the kings have come. He related that the King of Fire had the blade of a sacred saber associated with a host of spirits, and his power as a shaman was derived from his role as guardian of the talisman. Wol added that the Cambodians have the hilt and the Vietnamese have the sheath.

When asked about the sacred saber, he became very guarded, simply answering that it existed but it was forbidden for anyone to gaze upon it. The King of Fire listened, and, without changing expression, continued to smoke his pipe.

Hickey was luckier than a certain French colonial official named Prosper Marie Patrice Odend’hal, who demanded to view the sacred blade, and was murdered by Oi At, the then King of Fire. This provoked another short war- the Jarai had previously resisted the French between 1894-97- between the tribe and colonialists, and the King of Fire was forced to flee.

The Last Kings of Fire

Moura also wrote that until the reign of Norodom- which began in 1859- the Khmer kings sent annual tributes- often including a young bull elephant, metals and silk cloth to wrap the sacred saber. These gifts were taken upriver to the governor of Kratie, who was responsible for transporting them northwards to the highland ‘kings’.

In return, the Jarai elders would send a large lump of wax bearing the thumbprint of the King of Fire and two jars filled with rice and sesame seeds, along with the occasional ivory tusk and rhinoceros horn. The wax was used to make candles for ceremonies at the Royal Palace, and during times of the rice and sesame would be used in rituals to appease evil spirits.

Similar tributes were recorded in Vietnamese in the Đại Nam thực lục – Annals of Đại Nam- a 584 volume official history of the Nguyễn dynasty written between 1844–1909

Moura also reported that when King Ang Duong, during one of his reigns, was fighting a war against the Vietnamese, the Kings of Fire and Water sent him nine elephants. They were brought by Jarai mahouts to the capital at Oudong, and there was much celebration to welcome them. Laden with gifts, for the return journey to the highlands, some of the mahouts fell victim to smallpox (a disease associated with the King of Fire) and died on the return journey. The following dry season, the King of Fire sent a request to the Khmer king to have the mahouts’ bodies returned to their homelands.

After the remains could not be found, so Ang Duong arranged to have special gifts sent to the King of Fire as compensation.

In 1859, Ang Duong’s successor Norodom ended the traditional gift giving to the Kings of Fire and Water, and when some Jarai chiefs approached the governor of Kratie to inquire why gifts were no longer being sent, Norodom did not respond- thus ending the custom.

According to Hickey, the King of Fire was never directly addressed by the regular people, but through his ‘soldiers’- two assistants who accompanied the King.

When not performing rituals, the King of Fire lived at the periphery of society, and supported himself by his own labor and the gifts and donations from the tribe. Although revered, he was also feared and could bring bad luck to a house or village if he entered- smallpox being the main affliction associated with a unwanted visit.

“Since he derives his power from the Spirit of Earth and Sky he should avoid eating beef, frogs, rats, or animal innards. He should stay out of villages for fear of causing an outbreak of smallpox.”

Hickey described his attendance at one of these rituals:

The King of Fire’s assistant and some of the villagers had spread out rubber army ponchos on the floor of the grove. They also had hung some ponchos on the bamboo branches to keep out the rays of the white sun rising in a pale blue sky.

A large woven reed mat was spread out for the King of Fire. He squatted on it, smoking his pipe, and motioned for us to share the mat with him. This brought comments of approval from the group of men sitting on the slope because it was considered a great honor……

.…men from surrounding villages began to gather in or near the bamboo grove. Women appeared, but they stayed a good distance away. It was explained that they feared the powerful spirits associated with the king. A group of men entered the grove carrying a large drum and some gongs. They explained that the largest drum was the “mother gong,” the middle sized one was the “sister gong,” and the smallest, the “child gong.”

Gifts of tobacco were give, along with chickens and jars of alcohol.

A large cooking pot of river water was placed before the King of Fire, who reached over and took a shirt from his bundle of clothes. Dipping a sleeve of it in the water, he passed it to the men who had been preparing the jars. They wiped their faces and hands with it. Another man passed the king a glass which he filled with the water. The man washed his face, elbows, and knees with it.

When the food was ready, they placed it on a large banana leaf and put it near the jars, where the first assistant had placed some uncooked rice and buffalo flesh. He split the cooked chickens, put a lit candle next to them, and then put a tube into the jar. The King of Fire came forward and, squatting, took a handful of uncooked rice and cast it over the chicken and the candle. Then he held a rice bowl of water in his right hand over the jar while he chanted. Setting the bowl down, he continued to chant while he tore some flesh from the chickens, a gesture he repeated twice. The first assistant said each gesture was for a village that had made contributions to the ritual. He broke the remaining chickens into small pieces which he passed out to the villagers who had brought the offerings.

The King of Fire squatted by the alcohol jar and holding the tube with his right hand drank while the first and second assistants squatting in front of him clapped their hands. Then the first assistant began to grunt as he rose, swaying his body and moving his hands in a graceful gesture reminiscent of a Thai or Lao dance. Standing, he uttered squealing and trilling sounds before sitting again to clap his hands. He also poured water into the jar to replenish that drunk by the King of Fire.

When the King of Fire had finished his libations, the first and second assistants drank from the jar. Additional chickens were brought in, along with more jars of alcohol and bottles of Vietnamese beer, brandy, and soft drinks. I was invited to drink from the jars. Then all of the villagers began to eat and drink. Men and women approached the bamboo grove to hand in cups to obtain some of the water, with which they bathed their face, arms, and legs. The first assistant explained that when the King of Fire prayed over the water and touched it with an article of his clothing it became lustral water that would protect anyone who washed with it from evil spirits.

At 4:00 P.M., as the heat intensified and rays of sun glinted through the bamboo, men from other villages arrived, carrying large jars, chickens, and a sack of rice. They bowed before the King of Fire and presented their offerings. The jars were staked to the ground while the chickens were cooked. The ritual by the King of Fire and his assistants was repeated. At one point the king, who had drunk quite a bit, forgot the name of the village and had to be reminded.”

King No More

The last King of Fire died in the late 1980’s. In 1991, anthropologist Oskar Salemink met his designated successor Siu Aluân, who was never consecrated into the postition, apparently because of concerns of Highlander nationalism among the Vietnamese authorities. Siu Aluân died in 1999 without a successor being officially named.

The mythical sword has never been found- perhaps it is buried, or hidden in a remote cave waiting for the next King of Fire to channel its spirit. STEVE