On July 19, 1958, Beijing and Phnom Penh established formal diplomatic relations. Cambodia recognized the legitimacy of the People’s Republic of China and rejected Taiwan’s claims of independent statehood.

This caused uproar among the US and the neighboring countries of Thailand, South Vietnam , along with anti-communist elements within Cambodia.

Part of the reason given was that Sihanouk was growing more uncertain of his position, with economic policy and corruption proving unpopular at home, while his often erratic foreign policy- ‘the mercurial Prince’ was a term often used by US Ambassador William Cattell Trimble- caused alarm in Washington, Bangkok and Saigon.

A coup was plotted, with militia leader and sometime politician Dap Chhoun at its head and allegedly organized by Sam Sary, Son Ngoc Thanh with the aid of the Thais and Vietnamese.

Sihanouk’s intelligence services discovered details of the plot and on February 21, 1959 dispatched a battalion of troops to arrest Chhuon in Siem Reap. Chounn escaped in just a sarong, but a US citizen and alleged CIA radio operator, Victor Matsui, was captured. Chhuon was later apprehended, interrogated, and died “of injuries” before he could be properly interviewed. Sihanouk later alleged that the Minister of Defence, Lon Nol, had Chhuon shot to prevent himself being implicated in plot.

The USA denied having any hand in the coup attempt, but declassified document show that there was certainly knowledge, and that intel was not passed on to the prince.

For those interested in such things , dozens of related telegrams, cables and letters are listed in chronological order HERE (just click the arrow on the right to go through).

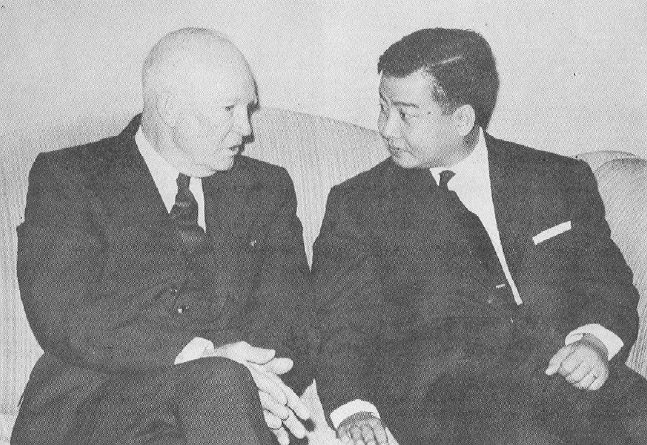

In the months before the attempted coup, on September 12, 1958, Sihanouk arrived in the US to attend the UN General Assembly. He made an unofficial visit to Washington between September 28-October 3.

Following the incident in Siem Reap, and after accusations- and official denials- Sihanouk penned a personal letter to President Eisenhower, republished here in full:

Phnom Penh, February 23, 1959.

Mr. President: I have not forgotten the cordiality of the welcome which you were so kind as to extend to me during my stay in your country last fall and it is because I believe I shall find comprehension and sympathy in you that I write you today to explain to you the gravity of the situation Cambodia.

My country, Mr. President, is a friend of long standing of the great American democracy. Like the US it detests oppression in all its forms and it can only voice its approval of the desire to which you gave expression in your last message on the State of the Union for a world “community of strong nations, stable and independent, where the ideas of liberty of justice and human dignity can thrive”.

Cambodia is not, as some have at times attempted to make me appear to say, boldly falsifying my thoughts, an enemy of SEATO, of which the US is one of the principal animating forces. We understand perfectly that our Asiatic neighbors make such agreements among themselves and great friendly powers to better defend themselves against Communist subversion. The fact that we do not belong to SEATO does not entitle us to criticize the organization as such. I add that we have full sympathy for the national regimes of other countries and that, although neutral (for special reasons), we do not proselytize for neutrality. Neither, in the final analysis, does Communism have any attraction for us, which up to the present has not succeeded in taking root in our ancient nation, monarchist, socialist, and nationalist.

However, our small, pacific country whose Army numbers scarcely 30 thousand men and whose Air Force and Navy are purely symbolic, is the object of grave threats of aggression on the part of neighbors both larger and more powerful. Rebel troops and brigands are concentrated on our frontiers on the west and on the east and are supplied with modern arms, a small party of these troops has already penetrated into our western provinces.

A very large sum of money has been given to the Commander of one of our military regions, that he may declare himself autonomously, whose arms are delivered to him by foreign planes, and we have had no other recourse than to send the Royal Forces to enforce respect for our national integrity. We have discovered in our capital and in our provinces the existence of a vast network of subversion fed by our neighbors with the aim of forming a puppet government ready to align itself to their policy and to give its consent to various concessions. These facts, Mr. President, are certainly not known to you. Because of their extreme gravity and because of the fact that they threaten our national government, twice approved by the people in free elections, I dare to solicit the speedy intervention of the friendly government of the US of America with our Thai and South Vietnamese neighbors, so that they will return to a policy of good-will and loyal neighborliness toward us. I know, Mr. President, that the Government of the US considers our neighbors as sovereign states into whose affairs it does not wish to inject itself. I wish to point out, however, that the strength of those countries is derived from the assistance which they obtain from the US which makes available to them, in addition to its moral support, large credits and important armaments for the purpose of defending their independence against Communist subversion.

The US is in my opinion twice entitled to make its voice heard. First of all, as a firm supporter of the United Nations (whose seat is on its territory) and whose constant doctrine is respect for the sovereignty and the integrity of its member states. Next, in order to see to it that the credits and arms which it turns over to nations in order to protect themselves from the Red menace are not unrightly used to support territorial and political ambitions or policies against non-Communist neighbors.

The Ambassador of the United States of America in Cambodia did not believe—and rightly—that he was interfering in our affairs when he pointed out to us that his country would not permit us to use arms which we had obtained from it against our neighbors. I ask you to have your representatives to our neighbors take the same position.

I am ready to go to great lengths to reassure the latter, and American opinion as well, to whom it has often been said that Cambodia lives under a “dictatorship” and does not approve the policy of neutrality which I am supposed to “impose” upon it.

I am ready to resign with all my government, to dissolve our National Assembly, and to call the people to new elections, in which all the parties in opposition to the Sangkum Reastr Niyum, over which I preside, will be able to participate freely—even those of MM Sam Sary and Son Ngoc Thanh.

I suggest that these elections be held under the control of the United Nations and that among the observers named by this organization be included the Thais and, although South Vietnam is not yet a member of the UN, also the South Vietnamese.

I think that in this way no one will be able any longer to have doubt about the will of our people. I commit myself, moreover, to withdraw from politics if views hostile to the Sangkum Reastr Niyum and to neutrality should obtain the majority. I think that American opinion, and you primarily, will recognize the fairness of this democratic proposition.

The very great confidence I have in you, Mr. President, the respect which I have for your eminent qualities as a statesman and an unquestioned leader of the free world, make me hope that you will be willing to attach special importance to the anguished appeal which I address to you in my country’s name.

I am certain that you will not permit a small country, friendly to yours, friendly to all the larger democratic nations, to be the object of an aggression encouraged by your allies and that you will know, with all the firmness which everyone admires in you, how to cause the very grave threat which weighs on us to recede.

Only the intervention of the United States of America can save the free Khmer democracy from an unjust and unmerited subversion, entirely artificial and mounted from without, as elections organized under the most severe international control would clearly demonstrate.

If, although I can not imagine it, this intervention should not lead to satisfactory results, I ask you to give us at least the means to defend ourselves by ourselves, without having to solicit them from other nations.

America, in whose wisdom and friendship I want to believe, can not let us be erased, by its silence, from the map of free nations nor let us slip into an anarchy from which the [garble] would be the only ones to profit.

I ask you, Mr. President, to excuse this plea, which may be too impassioned, which I have presented to you in the name of my people. I have faith in your sense of justice, you who have evoked “the shining prospect of seeing man build a world where all will be able to live in dignity.”

I beg you to accept, Mr. President, the assurances of my highest consideration.

Norodom Sihanouk

President of the Council of Ministers of Cambodia

There was obviously more correspondence, but the reply that has been declassified (and available) was penned by Eisenhower in May.

Washington, May 7, 1959.

Dear Prince Sihanouk: I appreciate very much the friendly sentiments which you expressed in your letter of April 13, 1959, from Paris and I read with interest your further explanation of several points raised in your earlier letter of February twenty-third.

With respect to your observation that Cambodian rebels are openly claiming United States support, I wish to assure you most emphatically that the Government of the United States is in no way supporting any efforts to overthrow the Monarchy or the duly constituted Government of Cambodia. Any claims to the contrary, whatever the source, are without the slightest foundation. I shall request the United States Ambassador at Phnom Penh to discuss with the appropriate officials of your Government the nature of such claims and the means to counter them should this be deemed necessary.

Your comments on the marked improvement in relations between Cambodia and Thailand are most reassuring. I trust that the reiteration by you and President Diem of the desire for friendly relations foreshadows a similar, mutually profitable understanding between Cambodia and Viet-Nam. You may be sure that the United States will follow the development of amicable relations among the countries of Southeast Asia with active and sympathetic interest. In particular, I hope that it may soon be possible for positive steps to be taken toward the resolution of the outstanding differences between your country and its neighbors. American Ambassadors in the area stand ready to encourage the development of mutual confidence, and, wherever possible, to lend friendly assistance to specific endeavors toward this end.

I have taken serious note of the comment toward the end of your letter indicating your desire to enlist the interest of the United States in the future of a small country such as Cambodia, and I wish to reassure you on this score. As a matter of principle, the disparity in size and material resources of our two countries in no way affects the genuine concern of the United States in Cambodia’s welfare. It is also part of American tradition that we feel a keen sympathy and understanding for the aspirations of other countries, whether large or small, to achieve and maintain their freedom. Finally, as a matter of purely personal association, I recall that my inauguration as President occurred in the same year that Cambodia, largely through your efforts, finally gained the full measure of national independence.

I believe you will agree that active American interest in Cambodia has been demonstrated not only in words but also in tangible assistance intended to help your country maintain its independence and further develop its material resources. This assistance has been provided in complete conformity with the respect of the United States for Cambodia’s sovereignty, which includes respect for Cambodia’s sovereign right to choose its own means of protecting Cambodian independence and contributing to the common goal of world peace. As long as Cambodia subscribes to these aims, you may confidently rely on American friendship and understanding.

Since last communicating with you I have heard of your operation in Paris. I take this opportunity to convey my best wishes for your speedy and complete recovery.

With warm regard,

Sincerely,

Dwight D. Eisenhower

One thought on “Today In History- Sihanouk Writes Eisenhower”