The brutality of war has, since time began, countless times destroyed not only lives, but great cities and cultural legacies. Despite the suffering inflicted on the Cambodian people during the 1970’s, one of the few positive outcomes for future generations was that Angkor Wat and surrounding temples escaped the conflict relatively unscathed- despite it being occupied by the North Vietnamese and Khmer Rouge for almost 6 years.

For clarity, the National Liberation Front of Southern Vietnam (NLF) are referenced in contemporary sources as ‘Viet Cong’, likewise, the PAVN is referred to as the NVA.

Loss Of Angkor, June 1970-January 1972

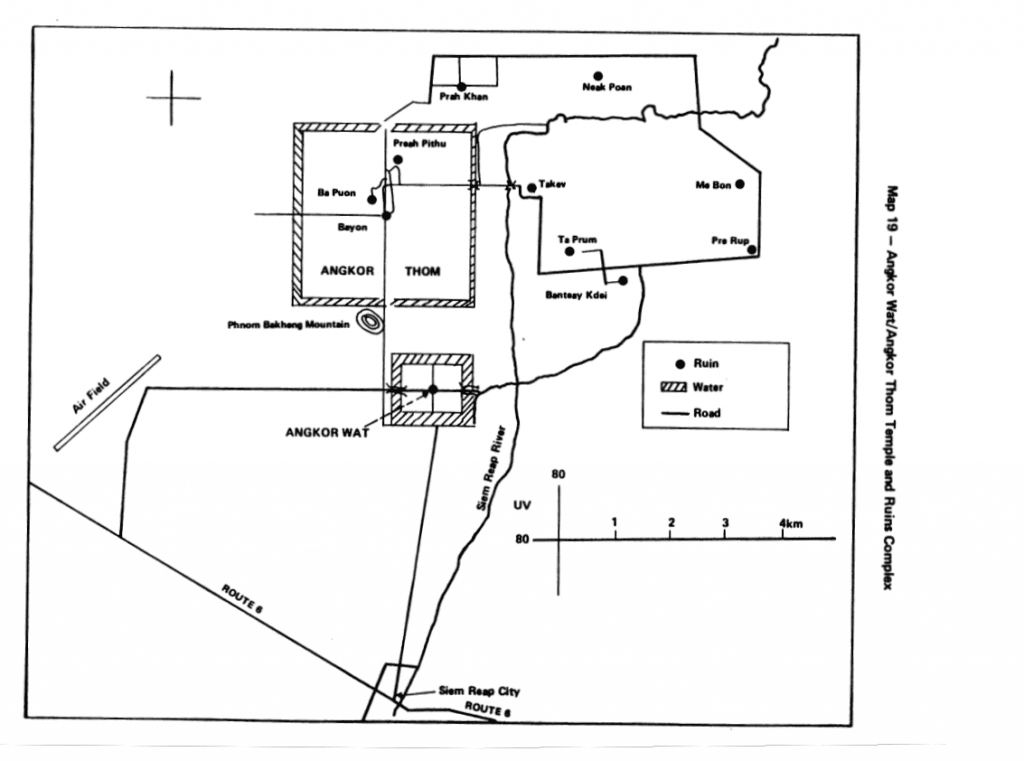

The ruins of Angkor Wat had been controlled by the NVA and allies since the night of June 5-6, 1970. North Vietnamese forces of the 203d Regiment also attacked and overran Siem Reap airport. FANK troops (likely from the 12th Inf. Brigade and possibly some 10th Inf. Brigade from Oddar Meanchey) retreated to Siem Reap town. The communist forces, after a brief attempt to take the town, were repelled and reinforced positions inside the temples.

Most of the Vietnamese troops had retreated westwards from the Cambodia-Vietnam border, after the bombing raids of ‘Operation Menu‘ and the US and South Vietnamese incursion of 1970’s ‘Cambodia Campaign’- a tactical blunder overlooked by the planners in Washington.

Yet, despite the war, tourists were still arriving in Siem Reap, mostly via Bangkok. Thai officials expressed surprise and apprehension over the reports of the fighting near the Thai‐Cambodian border.

Tourist agency sources said more than 100 travelers, mostly Americans and Europeans had made plans to visit the Angkor Wat ruins that week. One travel agency official said he believed “all or most of the tourists” had left Siem Reap before the Communist attack. (NYT)

For the next 18 months the frontline remained around Angkor Wat, and an unofficial truce, save for intermittent mortar and rockets fired by both sides, was observed. But at least one battalion of North Vietnamese army and a large number of Khmer Rouge fighters- a total of perhaps 4,000 fighters- had control of the temple complex.

In Siem Reap, the 12th Infantry Brigade- made up of volunteers from Battambang and Siem Reap defended the town.

The Stalemate

It was a curious situation, and not one well-recorded in the history of the Cambodian civil war of 1970-75. 1,000 or so uniformed and disciplined North Vietnamese had openly taken control of the symbol of modern-day Cambodian identity. Also, since the deposing of Sihanouk, fringe local communist factions- previously seen as little more than a nuisance- now had support from many rural Cambodians- and more dangerously, the tutorage of a battle-hardened NVA apparatus with three decades of combat experience against superior armies.

The Thai government were certainly concerned by developments so close to their border, and considered sending troops (how they were dissuaded would have to be investigated further). The northwest of Cambodia had been under Thai control from 1795-1907, was annexed during World War II, and returned in 1946. The region was still considered by many of the Bangkok elite as lost territory, and still rightfully in their sphere of influence.

There was no obvious purely military advantage for the North Vietnamese to capture Siem Reap town- it was too far away from the Vietnamese border for resupply or to achieve the objectives of the secretly planned Spring Offensive against the south. The occupation of a major urban center so close to Thailand would also almost certainly have provoked some form of response from Bangkok. However, controlling Angkor was a PR coup, and could showcase the Vietnamese Communist’s standard of maintaining order, while also training up the local communist forces.

The Khmer Rouge, as a Life Magazine wrote in July 1970, ‘captured documents’ ‘make clear their (the NVA) strategy of undisguised psychological warfare aims of raising a homegrown liberation army of Khmer Communists to overthrow Lon Nol.’

North Vietnamese soldiers were under strict instructions to behave well- towards monks, women and children, to respect pagodas and not to steal. The captured document from 1970 warned NVA forces of severe punishment if ‘even a needle and thread is taken from the locals.’

On the other hand, South Vietnamese ARVN troops had plundered and raped across much of the area of their operations in 1970. ‘Another six months of this and you will not have a nation of Cambodian nationalists, but an army of Khmer Cong‘ one FANK major was reported as saying, after ARVN soldiers looted Kampong Speu, and raped four teenage girls in the weeks before Angkor was taken.

The stand-off continued into 1971, with press reports from the CIA announcing ‘defections’ by some Vietnamese officers in 1971. The language of propaganda, with hindsight, speaks volumes:

For the Khmer Rouge- technically fighting under the leadership of the ousted Sihanouk as part of the GRUNK government in exile- the propaganda victory of taking, and holding the symbolic site would have been huge, and legitimized their claim to be fighting for the Cambodian people.

The Northwest had long been a hotbed of insurrection- with the Thai sponsored Khmer Issarak movement morphing from an anti-colonial, to anti-Royalist, to a pro-communist group between the 1940’s to 1970’s. Peasant uprisings in Battambang in the late 1960’s- ironically, against the Sihanouk led government in Phnom Penh- were brutally put down under instruction from the then Prime Minister Lon Nol. In short, there had long been antipathy for the urban elite from the rural north.

The holding of Angkor would have been a way to not only unite the various anti-Republic factions under the new ‘legitimacy’ of the Sihanoukist cause, but also draw in new support from the local population- who may not have been particularly supportive of the Khmer Communist movement.

The Republican army- FANK- according to Major General Sak Sutsakhan in his book ‘The Khmer Republic at War and the Final Collapse’, had little enthusiasm for turning Angkor into a battleground, citing concerns over damaging the iconic monuments. Another reason that has not really been investigated is the connection between the local rebels and the FANK military members.

Sak Sutsakhan himself was from Battambang, and a cousin of Nuon Chea– AKA Brother Number Two in the Khmer Rouge. As most of the FANK’s 12th Infantry Brigade were from the local area, it is highly likely that some- both in the command and rank and file- had family members who had answered the call by Sihanouk to join the rebels. There were several recorded cases in the later war of the 1980’s of family and neighbors coming across each other from different sides, and others of soldiers crossing the frontlines to meet relatives.

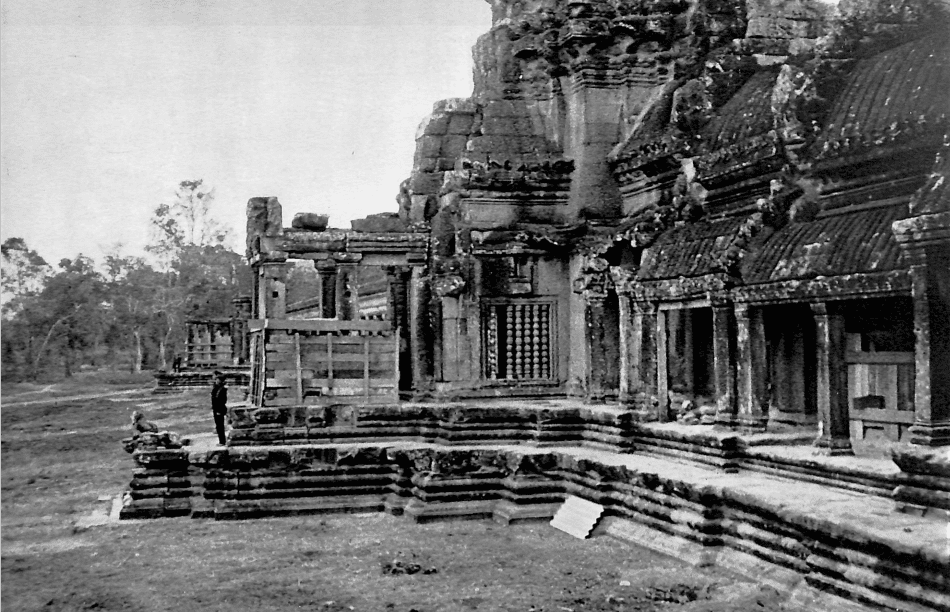

A few stray shells had landed around the main site of Angkor Wat, but much of the damage caused during this time seems to have come from the looting of statues and carvings- many of which began to appear in the hands of Bangkok and Hong Kong antiquities dealers.

French archeologists under Bernard Philippe Groslier were later expelled, and some Cambodian staff working for them were arrested. Around 20 were reportedly executed for ‘providing information to the Central Intelligence Agency.’

Operation Angkor Chey

At the end of 1971, the Khmer Republic’s disastrous Operation Chenla II had virtually wiped out ten infantry battalions (including some of the best Khmer Krom battalions) and resulted in the loss of another ten battalions-worth of equipment, which included two howitzers, four tanks, five armored personnel carriers, one scout car, ten jeeps, and about two dozen other vehicles.

However, instead of pressing the advantage, the People’s Army of Viet Nam (usually referred to at the NVA) and their allies went quiet. Although unknown at the time, the NVA was busy planning and preparing logistics for the surprise attack on South Vietnam- what was known as the Easter Offensive or Spring-Summer Offensive.

Following the catastrophic loses of the Chenla II campaign, on January 10, 1972, the FANK retreated from the Cambodian-Vietnamese border around the ‘fish hook’ and an operation around ‘the parrot’s beak’ failed to reach any objectives.

The next FANK offensive was smaller, designed regain control of the nationally symbolic Angkor Wat, from Communist hands. The operation was most likely as symbolic as it was strategic- as the third year of the civil war began, the Republic had lost control of much of the countryside and were fighting to keep the main routes between the main urban areas open and towns supplied. Retaking the national symbol would have been a great morale boost- especially after the 1971 commando raid on Ponchentong airport had shaken the Republic.

The plan was to encircle the temples and cut off supplies. Initially the operation was marked by small scale skirmishes along Route 6, east and west of Siem Reap. On February 8, a counterattack drove back FANK units, but was stopped thanks to airstrikes.

By the end of February, the operation had come to a standstill. In mid-May, FANK command received intelligence that communist troops were withdrawing to join operations raging in the east and southeast of the country. On the night of May 17 FANK troops moved across the frontlines around the airport towards the strategic high ground Phnom Bakheng, a 66-meter-high temple bluff just a few hundred meters south of the fortified Angkor Thom complex.

Only around 30 KR and 7 NVA defended the hill, and they were overrun quickly- giving the FANK the first notable success of the year. Just to the southeast stood the temple of Angkor Wat.

The following night, three FANK units scouted around the walls of Angkor. One unit reached the eastern wall and two others headed for the western entrance and the famous causeway.

Suddenly the sky was lit up by flares. Hidden communist defensive positions opened up with a deadly volley of crossfire. Soon one of the FANK units suffered 17 dead, with many more wounded. FANK troops continued fresh attacks from the west, but were pushed back by heavy fire from trenches and concrete bunkers dug around the temple. Khmer Air Force (KAF) flying North American T-28 Trojans- designed as trainer aircraft, but converted to close ground support- dropped napalm and explosives perilously close to the main temple and positions that had taken two abandoned tourist hotels 2 km to the south.

After the intense fire-fight, FANK withdraw to their positions, but held Phnom Bakheng- which allowed the airport to function.

Fighting raged around the country, but the stalemate of Angkor Chey remained mid-August, when the communists recaptured the high ground of Phnom Bakheng, threatening the airport.

With harassing fire again threatening vital air supplies, the FANK were forced to depend on the Tonle Sap and a new airfield to the south of Siem Reap town.

Until 1975, the frontlines roughly stayed the same. The Grand Hotel D’angkor, now the Raffles, was the headquarters for the FANK and for the rest of the period and with Communist forces controlling the route to Angkor Wat about 2 km to the north. No major initiatives were taken by either side until the end of the war.

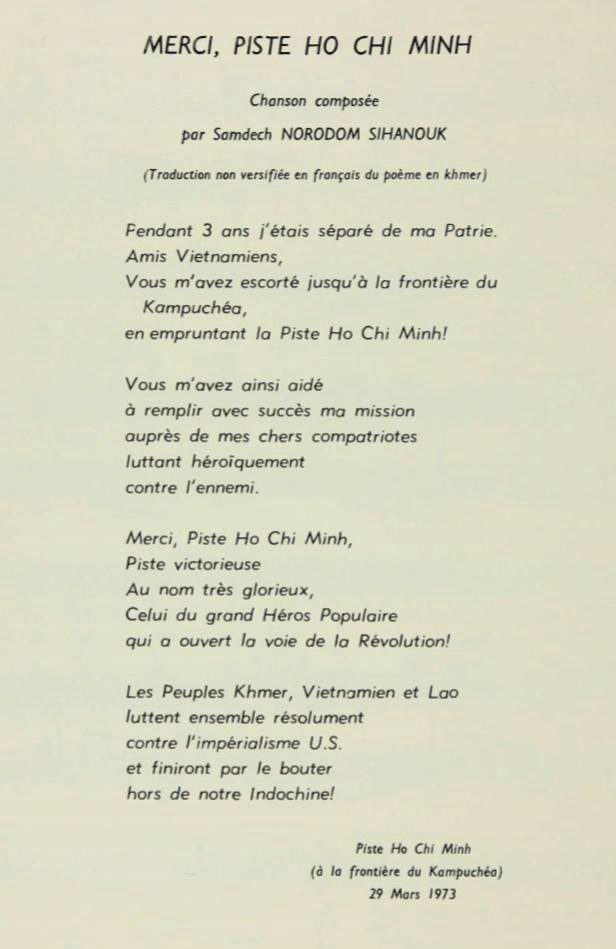

The situation was stable enough in 1973 for Sihanouk to visit Angkor, as part of his ‘long march’ into the Cambodia northern ‘liberated zones’. He met with his former foes-turned friends in the Khmer Rouge such as Hu Nim and Khieu Samphan, and the first ‘meeting of the Council of Ministers of the Royal Government of National Union of Cambodia in the Liberated Zone’ was held in the forest near Angkor. He also spoke at rallies held for the local poupla

So taken was the Prince by his trip and NVA escort along the Ho Cho Minh trail, he later composed a song, with lyrics in French and Vietnamese, extolling his ‘inspection’. The composition (without lyrics) can be heard here ‘Merci, Piste Ho Chi Minh/ Cảm Ơn Đường Hồ Chí Minh’

After the fall of Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975, the garrison at Siem Reap formally surrendered. The fate of the officers and soldiers was the same as elsewhere in the country- execution for those who were unable to blend in with the civilians and refugees who were herded from the city.

If there was a positive to come out of this battlefield, the ancient temples were left relatively unscathed. Restraint on all sides certainly saved the complex, which could easily have been destroyed- a fate that befall the ancient city of Hue in 1968.

*Photos below from a special supplement in Chinese propaganda magazine China Pictorial, No. 6, published in English, dated 1973.

Sources include: New York Times, Life Magazine, History.net, Sak Sutsakhan-The Khmer Republic at War and the Final Collapse, China Pictorial, Daily Report, Foreign Radio Broadcasts, Issues 221-230- United States Central Intelligence Agency, Le Minh Khai

One thought on “The Battle For Angkor 1970-1975”