This article continues from PART ONE

The Second FULRO Rebellion

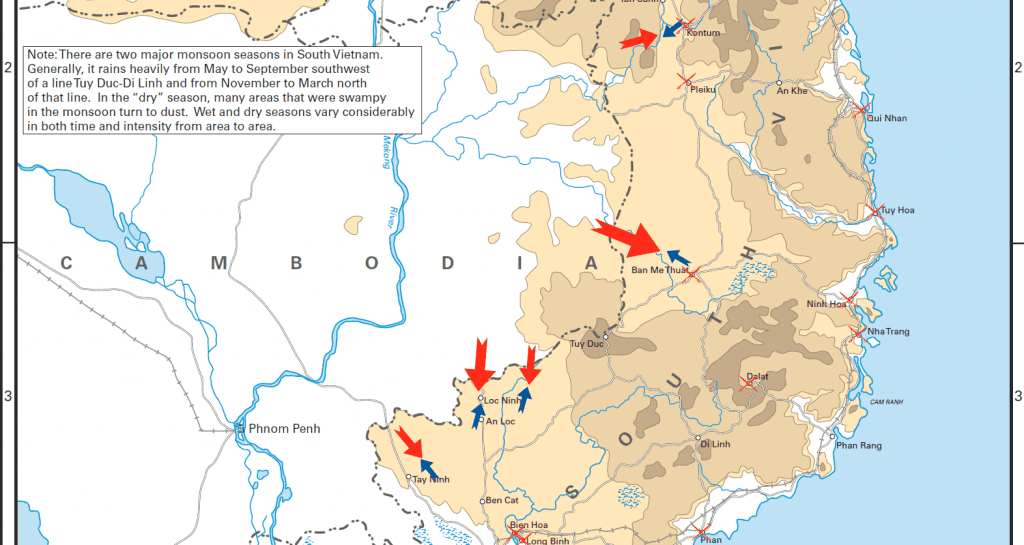

On September 15, 1965, 500 FULRO Montagnards assigned to Buôn Ma Thuộc received arms, following the latest settlement between the Saigon government and the movement’s leaders. Then, just weeks after the battle at Ia Drang, on December 12, militant FULRO rebels, led by Y Bhon Adrong, attacked Phú Thiên, killing 32 South Vietnamese soldiers and wounding 26 others. They then stormed the administrative department and sub-district, killed more Vietnamese and raised the FULRO flag. Most retreated back into Cambodia in the following days, but four were captured, tried and later executed. 15 others were imprisoned. Rumors abounded that the spirits of the dead visited Y-Bham Enoul, asking for revenge.

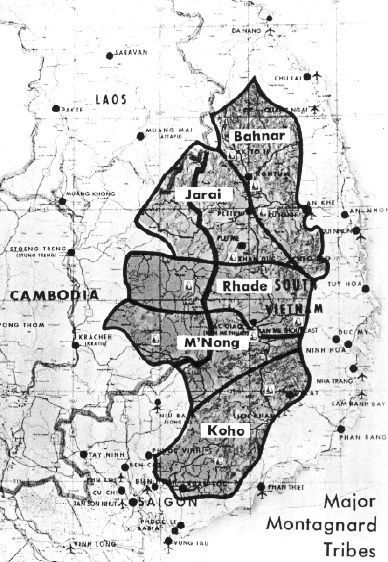

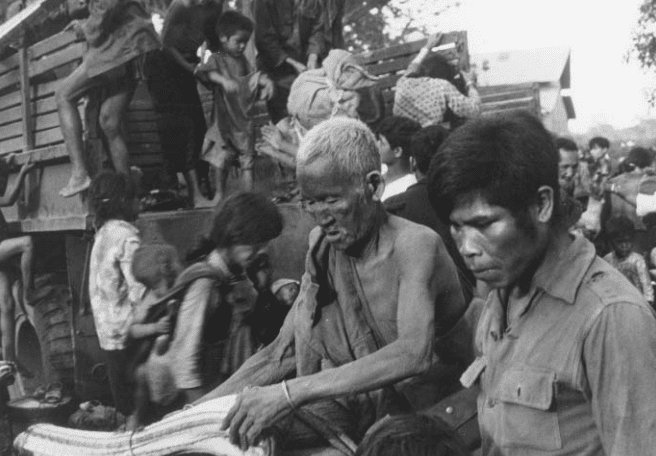

A major factor behind this second revolt were Vietnamese Kinh refugees escaping the war in other provinces- or following the new American buildup in Pleiku and other towns, bringing bars, brothels and other ‘entertainment centers’. As they flooded into the Central Highland- often living in squalid conditions- many Montagnard people, in turn, fled into territory under control of the North Vietnamese.

FULRO leaders also complained that North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong would enter Montagnard villages to extract ‘taxes’ and kidnap young men to use as laborers. In turn, ARVN forces, they accused, were more interested in rooting out FULRO and looting private property than fighting the Communists.

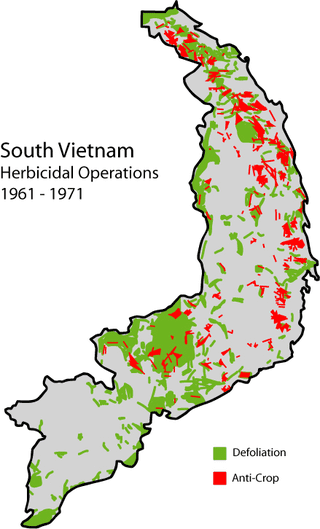

Saigon, who’s permission was needed before US airstrikes were called, appeared keen to allow bombing of the Central Highlands, while reluctant to allow attacks on low land areas. Military use of herbicides saw millions of gallons of chemicals such as Agent Orange sprayed over Vietnam, poisoning the land and crops. All in all, life for the Montagnards was becoming unbearable.

The charismatic FULRO leader Y-Bham Enuol- who followers believed could converse with spirits- and, strangely, the spirit of the still-very-much-alive Charles de Gaulle- continued to camp out in the forests of Cambodia with thousands of followers.

Splits & Compromises

Cracks soon appeared between the Cham/Khmer faction of the FULRO alliance, as, on September 20, 1966, Les Kosem – the ‘bearded Cham’ from the first rebellion- led Royal Cambodian Army troops to surround Camp le Rolland, in an attempt to move FULRO back into Vietnamese territory. Lt. Col. Y Em managed to rally reinforcements and the Khmer forces were driven back. The movement had apparently lost the full support from the Cambodian factions, and now were unwelcome in Cambodia and South Vietnam.

On 15 October 1966, eight hundred FULRO troops arrived in Pleiku for Highland-Lowland Solidarity Conference on Air America (the CIA-funded airline). They began to complain about the treatment they received- no blankets, water etc. in their tented quarters, and were not involved in the organization of the event. Celebrations were described as ‘plastic’ and performances designed by the Vietnamese to highlight Montagnard culture- whether by accident or design seemed to reinforce the stereotype of ‘the noble savage’.

To compound efforts being made by MACV-and an ever-increasing CIA presence- in 1967 the Northern sponsored National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) announced its intention to “implement the agrarian policy with regard to peasants of the national minorities. To encourage and help them to settle down to sedentary life, improve their lands, develop economy and culture” And granted the minorities the right to use their own spoken and written languages and “maintain or change their customs and habits……in the areas where national minorities live concentrated and where the required conditions prevail, autonomous zones will be established within independent and free Vietnam.”

The US responded by evacuating whole villages- such as those inhabited by Jarai- killing livestock, burning homes and fields and resettling the Highlanders into areas totally unsuitable for their farming methods and lifestyles. The emptied areas were transformed into ‘Free-Fire Zones’- with anything moving considered a legitimate target.

Cambodia began to experience internal problems of its own by 1967. An uprising in Battambang in 1967-68 was a sign that Sihanouk’s Sangkum government was growing increasingly unpopular in the countryside. China had failed in the promise to keep the North Vietnamese in check, and NVA/Viet-Cong bases had been established inside the Cambodian border, and a new Cambodian Communist group, the Khmer Rouge, was arming itself under the guidance of Vietnamese communist groups.

Sihanouk leaned back towards the west and any lingering support for cross-border revolutionaries was cut.

Between a Rock & a Hard Place

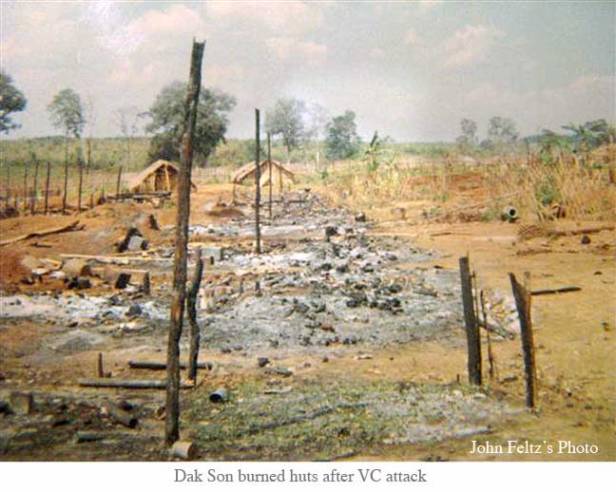

The North Vietnamese continued to harass Montagnard villagers, with on the worst attacks taking place on 5 December 1967 at Dak Son, a Stieng refugee village near Song Be.

According to Ralph Haupers, the SIL staff member working on the Stieng language, the Communists had been sending warning notes to the camp, ordering the villagers to join them on the Cambodian border with the threat of “punishment” if they did not. Undoubtedly the Stieng were to be used as bearers in the movement of arms and supplies through the area. Few villagers obeyed, so the North Vietnamese assaulted the camp. The men rallied to the defense with their spears, crossbows, and the few rifles some possessed while women and children hurried to the bunkers. The Stieng defenders were no match for the Communists with their sophisticated Russian weapons. Once inside, the attackers used grenades and flame throwers against the Stieng, killing more than two hundred of them. Haupers visited the village the following day to find charred bodies of adults, children, and tiny infants in the scorched earth of the bunkers. Their metal wrist and ankle decorations were melted into grotesque shapes. Survivors, many of them wounded and burned, picked through the ruins and ashes in the hope of finding some of their missing family members still alive. (Quote: Window on a War)

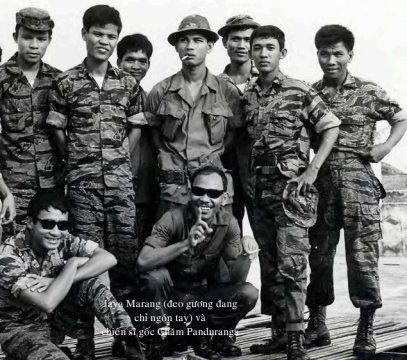

Although US Special Forces were forbidden to work with FULRO under direct orders from Gen. William Westmoreland were “not in Vietnam to support rebellion against the South Vietnamese government”, US forces on deep operations along the Ho Chi Minh trail would routinely ignore their superiors and use FULRO irregulars as guides. Some, such as Special Forces Lt. William H. Chickering would later admit to turning a blind eye as supplies and munitions were pilfered during his tour in 1967.

Moderate members of FULRO began to look towards political settlements with Saigon and returned to Vietnam, others signed up to Mike Force, but a more militant group remained in Mondulkiri.

The ‘Tet Offensive’ of January 1968 saw heavy fighting in the Central Highlands. FULRO troops fought against the initial waves of North Vietnamese forces as the attacked from across the Cambodian border.

“According to Y Dhe, when the attack began, thirty FULRO troops were stationed at the delegation headquarters in Buon Ale-A. Communist forces came through villages south of Buon Kram where we had visited Y Bham, and for two days and two nights the FULRO fought back. Y Dhe claimed that the movement suffered seven dead and four wounded, while they killed eighty-five Communists. The Communists captured some forty-five residents including two FULRO leaders, Y Ngo Buon Ya and Y Wik Buon Ya who also was a member of the Lower House in the National Assembly, and Benge reported that both were executed. Y Dhe described how the FULRO troops fought bravely but as American bombing became more intense they realized that they would have to evacuate. He, along with other FULRO leaders and their families, fled across fields to Buon Kosier. But Y Preh Buon Krong wept as he told how he and his family tried to flee just as an American air strike began. Several of his children were killed by a napalm bomb. Y Preh said, “My youngest son was hit by the bomb and we could not even find any remains.”

American Intervention

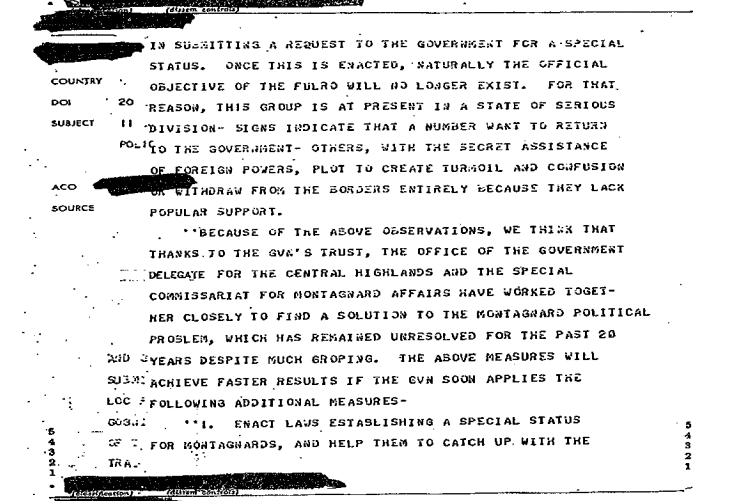

On December 11, 1968, discussions between the FULRO movement and the Vietnamese government-thanks to intense lobbying from the US Department of Defense and CIA- reached an agreement, of sorts. Some examples of the Americans position can be seen in declassified cables from 1967-68:

6. A matter which has been of considerable interest to us has been the status of the Statut Particulier drafted by a Congress of Montagnard representatives under the chairmanship of General Vinh Loc in order to meet some of the aspirations and concerns of the FULRO, most of whom are now in Cambodia, and other Montagnard tribes. Ky announced at the end of June that the Statut would be promulgated and the intention of the government to set up a Ministry for Montagnard Affairs, but no action has been taken. I brought up the matter with both Thieu and Ky. Thieu said he was presently examining the Statut, that he thought it was in order and conformed to the Constitution and proposed to promulgate it in August at a ceremony in Pleiku or Banmethuot. This should be helpful in stimulating the return of the approximately 2,000 to 3,000 FULRO now in Cambodia and giving the Montagnards generally a greater feeling of identity with the social structure of the country. (Telegram From the US Embassy in Vietnam to the Department of State- Saigon, August 2, 1967)

He (*Gen. Westmoreland) thinks the attack (*by Viet Cong) on Duc Lap Special Forces camp was for this purpose. It is in a remote area and manned by CIDG personnel. They (*VC) brought considerable forces against the camp and blew a bridge on the only route. We reinforced the camp with Army infantry battalions and used tactical air to put back the attack. A political reason for this attack against the Special Forces camp was to attract the native tribesmen (*Montagnards) to their side. Their chief leader (*Y-B’ham) recently visited Saigon to work with the Saigon Government on better arrangements between the FULRO movement and the Saigon government. The enemy is trying to impress these tribes with the feeling that the enemy is going to win and this would stop the growing rapport between Saigon and FULRO. (FOREIGN RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES, 1964–1968, VOLUME VI, AUGUST 1968)

Major concessions made included:

• Withdrawal of the land ownership decrees of ‘58 and ‘59 denying the Montagnards title to tribal lands

• The establishment of a Junior Military School to educate Montagnard children.

• Montagnards may enroll in Thu Duc Military School if they possess a diploma for 4 years of high school. (Vietnamese must have a diploma for 6 years of high school).

• Vietnamese and Montagnard dialects will be taught in the Montagnard primary school program.

• When competing with Vietnamese for schooling or jobs, 10% will be added to the grades of Montagnard applicants.

Montagnards were also allowed to elected in the provinces where they formed the majority, and local armed forces were placed under the command of a Montagnard officer. Y-Bham Enuol was also granted permission to return to Vietnam.

This agreement further isolated the Cham and Khmer Krom factions- the demands for a new Champa and the return of Kampuchea Krom were fanciful and naïve, even for radical 60’s movements, and had no place in an escalating war situation.

On December 30, 1968, after the Army of the Republic of Vietnam sent a helicopter to Camp Le Rolland to meet with Y Bham Enuol. As it left, carrying some fighters back to Vietnam, Royal Cambodian Army forces, led by former FULRO Cham leader Les Kosem, surrounded the base and captured Y-Bham, taking him to Phnom Penh and placing him under house arrest in the residence of Colonel Um Savuth.

On February 1, 1969, a final agreement was signed, signed by Paul Nur, on behalf of the Republic of Vietnam , and Y Dhơn Adrong. Those dissatisfied Montagnards remained in Cambodia with Cham and Khmer Krom, continuing to fight against ARVN, and sometimes siding with the Viet-Cong- who in some instances treated injured FULRO fighters in exchange for temporary cease fires.

The population at Camp De Rolland dropped from as many as 4,000 fighters and their families at the movement’s peak, to a few hundred by the time that Sihanouk was ousted in March 1970.

Lon Nol, who had been pivotal in the fight against communist insurrection during the 1960’s, must have had knowledge of, if not direct contact, with FULRO groups through Les Kosem before 1970. With extreme anti-Vietnamese Khmer nationalism being touted in government and on the streets, FULRO became useful again.

Some Montagnard FULRO members had been given commission in the Khmer National Armed Forces (FANK) and were living with their families in apartments on Monivong Boulevard, across the street from a military compound where Col. Les Kosem had a house. Y Bham Enuol was still in the villa of Col. Um Savuth near Pochentong Airport. One ‘new generation’ FULRO/FANK officer named Kpa Doh- a former translator for US Special Forces- told Gerald Hickey that it was necessary to keep the movements grandee in protective custody to prevent his “selling out” of FULRO to Saigon. Divisions in the military wing persisted, with Montagnard leaders complaining that Les Kosem would refer to them as “little mountain brothers” and tried to dominate military operations. Another notable Cham member was eminent Champa historian Po Dharma, who after being wounded in Kampong Thom in 1970, emigrated to France.

Lon Nol allowed ARVN and US forces to invade Cambodia in late April 1970, in what was known as President Nixon’s ‘Cambodia Campaign’. Kpa Doh claimed that FULRO forces, backed up by American artillery in the Ratanakiri-Pleiku border area had mounted an operation against Communist forces on 24 June, in the final week of the incursion.

FULRO leaders made trips from Cambodia into South Vietnam to try to recruit new members- with assistance from the CIA- but the optimism of the early years had waned and war weariness appeared to have set in.

Between 1971-72 most US ground troops had been pulled out of Vietnam, and military operations handed over to Saigon under the ‘Vietnamization’ program. Montagnards who had been with Mike Force were integrated into Vietnamese run units, and there were many reports of them being treated like cannon fodder by their commanding officers.

Waves of attacks from the North Vietnamese had caused a refugee crisis across the country, and thousands of Montagnards were placed into squalid camps. Corruption was rampant in the South Vietnamese government and military, with foreign aid that poured siphoned and pillaged. FULRO members inside Vietnam worked in the camps, distributing what was available to Highlanders. By mid-1972 it was estimated that 150,000 displaced Highlanders were living in camps and 200,000 had been killed in the war (out of a 1960 population of around 1 million).

Hickey made several visits to these appalling camps, describing them in great detail. “Who,” two FULRO leaders asked, “will be our mother and father when the Americans leave?” They described how Vietnamese were land-grabbing which precipitated fights between them and Rhadé villagers. They were also concerned about the illegal logging that was destroying much of the forests and the unexploded shells and mines causing deaths and injuries.

By November 1973 splits within FULRO had led to some units collaborating with local Viet Cong forces, who by around March 1974 began using them as a front to gain Rhadé villagers’ support. Some groups began negotiating lucrative timber deals with the North Vietnamese.

Four North Vietnamese divisions moved into the highlands under command of General Van Tien Dung. FULRO troops in the area did not inform the South Vietnamese of this build-up of Communist forces, and Buôn Ma Thuột fell on 12 March 1975. The Central Highlands was abandoned by the South, and ARVN withdrew to defend Saigon.

Phnom Penh fell to the Khmer Rouge on April 17, 1975. FULRO leader Y-Bham Enuol was taken from house arrest and, along with other members of FULRO, including Kpa Doh and Cambodian military and officials took refuge in the French Embassy. They were all removed by the Khmer Rouge and trucked away- none were seen again.

Les Kosem escaped to Malaysia, from where he made efforts to evacuate Muslim Chams from Cambodia. He died there soon after, with some suspecting he was poisoned.

After the fall of Saigon weeks later, FULRO forces regrouped under Brigadier General Y Ghok Niê Krieng and continued to fight against the new government of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Hopes of American assistance soon faded, but limited support came from China. Relations with the Cambodian communists remained tense, but Chinese influence possibly kept the Khmer Rouge from turning on the group, who were still largely based in Mondulkiri.

Following the Vietnamese backed invasion of Cambodia in late 1979, FULRO allied with the GRUNK government in exile. Chinese supplies were delivered via the Khmer Rouge and as many as 7,000 fighters remained in Cambodia from where they launched cross border attacks on Vietnamese army and police outposts.

The movement began to splinter. Some leaders surrendered to the Vietnamese and were ‘re-educated‘, others were captured. In 1980 a unit of over 200 fighters moved Khmer Rouge territory on the Thai-Cambodian border. Catholic aid charity CARITAS came under harsh criticism for their alleged involvement in helping FULRO member cross into Cambodia.

A 1984 air campaign by the Vietnamese, using Russian An-26, which ironically dropped US bombs such as MK81’s left behind in stockpiles, decimated FULRO and Khmer Rouge bases along the Cambodian border, followed by an infantry assault.

In 1985, 212 FULRO fighters, under the command of Brigadier General Y Ghok Niê Krieng and Pierre K’briuh, crossed into Thailand and were told that the Americans were no longer interested in fighting the Vietnamese. They applied for refugee status through UNHCR, and eventually ended up in the US state of North Carolina.

The Khmer Rouge cut ties with FULRO in 1986, and the Chinese aid they supplied ceased. According to Khmer Rouge official in a 1992 Phnom Penh Post interview the fighters had “no political vision”, and “very, very brave, but they had no support from any leadership, no food and did not understand the world around them”.

A former FULRO fighter, named Y’Khiem Ayun, who joined Mike Force aged 14 and was deported to the US after he was captured and imprisonment in Vietnam in 1990-91 said in an interview “We fled to Cambodia and fought from there because there was no homeland to remain on. The local people in that region hid us from their own communists while we fought the Vietnamese ones”

In 1992, journalists Micheal Hayes and Nate Thayer came across the remnants of FULRO’s forgotten jungle army, still hiding out in Mondulkiri. Some who had served in American units spoke English, and asked when the US was going to send supplies- 17 years after the last chopper had flown from saigon. They also asked of their leader Y-Bham Enuol. When informed of his presumed execution in 1975, Thayer wrote that they sat in stunned silence, with some openly weeping.

The group’s leader requested to meet with the American Ambassador to discuss the aid promised in 1975, and to seek proof of the death of their leader. “We are the troops of President Y Bham Enuol. If he has died, we want proof from the United Nations. The Americans had a whole plan for Indochina. I want to meet face to face with the American ambassador. I have a plan for the future, and they should know clearly our position for the revolutionary struggle. We want to know whether they will help us or not.“

Montagnard leaders in the U.S. sent messages urging the remaining fighters to lay down their arms including from Pierre K’briuh, who had escaped to Thailand in 1985 “Due to unfavorable circumstances, I suggest it is time to stop fighting, to find different ways to reach our ultimate goal”.

The UN, then in Cambodia to organize elections in the new post-Vietnamese Cambodia, met with the fighters in early September 1992. The FULRO forces were unwilling to surrender, unless they received protection from the UN- none wanted to return to Vietnam and face almost certain detention.

“We have enough problems in Cambodia dealing with the four factions, and now this army we never even heard of turns up” one UNTAC military official was quoted as saying in the Phnom Penh Post.

In October 407 FULRO soldiers and their families finally surrendered and handed their weapons to the UN peacekeeping force. They received refugee status through the UNHCR and with most later resettled in Greensboro, North Carolina- home to the largest Montagnard community outside of Southeast Asia.

“The Montagnard people and the Americans are like one family,” said a Lt. Col. Hinnie to Thayer. “I am not angry, but very sad that the Americans forgot us. The Americans are like our elder brother, so it is very sad when your brother forgets you“.

Issues still remain contentious in 21st century Vietnam, where ethnic minorities- Montagnard, Cham and Khmer-Krom still suffer persecution. The Montagnards, perhaps because their fate was the most recent, stand out as a people who were caught up in the most vicious of wars, when all they wanted was to be left in peace.

*A few thousand words does not do this subject justice, and those interested should continue to read some of the excellent books written about this side of the Vietnam war. By using so many sources, some discrepancies may have been made. This piece was designed to inform and is not meant to be an academic study- HISTORY STEVE

Sources: William H. Chickering- A War of Their Own (NYT), Gerald C. Hickey- Window on a War, John D. Howard– The Revolt of the Montagnards, U.S. State Archives (Vietnam), Nate Thayer/Micheal Hayes-Phnom Penh Post, Michael D. Benge -The Montagnard Political Movements and FULRO, others highlighted.

Recommended reading: Tiger Man of Vietnam- Frank Walker, WINDOW ON A WAR: AN ANTHROPOLOGIST IN THE VIETNAM CONFLICT- Gerald Hickey (free e-book)