Malcolm Caldwell, left-wing activist and supporter of revolutionary movements everywhere, was murdered in Phnom Penh on 28 December, 1978. To this day nobody knows just who did it, or why.

He was a prize idiot when it came to politics, but he was also a very decent human being. Wikipedia summarises his career:

Malcolm Caldwell was born in Scotland, the son of a coal miner. He obtained degrees from University of Nottingham and University of Edinburgh. He completed two years’ national service in the British army, becoming a sergeant in the Army Education Corps. In 1959 he joined the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London as a Research Fellow. Although he met with conservative opposition within the School, he remained on its faculty throughout his life. As well as being an academic, he was an energetic and committed radical political activist. He was dedicated to criticising Western foreign policy and capitalist economics, paying particular attention to American policy. He was a founding editor of the Journal of Contemporary Asia, a journal concerned with revolutionary movements in Asia.

In late 1978 Pol Pot’s Cambodia was in trouble. The Vietnamese were on the point of invading (provoked, it must be said, by repeated and very bloody border incursions by the Khmer Rouge), and Phnom Penh was virtually alone in the world. What to do? Apparently the KR leadership decided to invite some friendly Westerners to visit, and through them ask the Americans to make common cause with Phnom Penh against the evil Vietnamese. Yes, it sounds crazy, but read on.

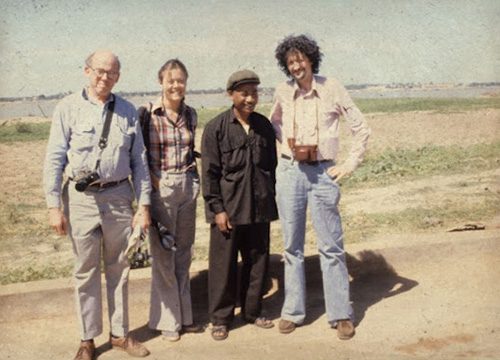

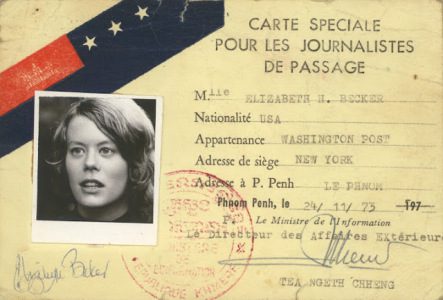

The invitees were Caldwell and two journalists, Elizabeth Becker and Richard Dudman. Caldwell was already a friend of the Khmer Rouge without being asked: a month earlier he’d written a piece in the Guardian rubbishing rumours of the Cambodian genocide; not only had the KR not killed anyone, but if they had it was only “arch-Quislings who well knew what their fate would be were they to linger in Kampuchea”. (Yes, I said he was a decent man, but I meant in his private life; people who met Caldwell generally liked him).

Becker and Dudman were more clear-eyed. Becker wrote a book, When the War was Over, in which she talks about the two weeks they spent in Cambodia as guests of the KR. She describes their situation as house arrest with guided tours, Phnom Penh as Pompeii without the ash, an absence of people and a sense of fear.

She also describes their group interview with Pol Pot, requested earlier but granted only on the last full day. There were in fact two interviews, one for Becker and Dudman, and separate one for Caldwell. (Note: most of the online sources seem to assume that Caldwell was included with Becker and Dudman in the first interview, but in Becker’s book she says “we granted an interview together,” which I take to mean herself and Dudman, and “Caldwell a separate one.”) The Becker/Dudman interview turned out to be more of a royal audience. After some photos they were seated at a respectful distance with their translators while Pol Pot filled them in. Vietnam, he said, intended to invade Cambodia. It would be aided by the Warsaw Pact. The invasion would not stop at Cambodia’s borders, Russian tanks would roll on to Bangkok and Singapore. NATO and Asean must not stand by. World peace was in the balance. You may go now. Caldwell came back delighted from his own interview, slightly later. He and the KR leader had discussed economic theory, and Pol Pot had invited him back next year. All three agreed the trip to Cambodia had been worth it. That night Becker was asleep by 11.00.

A few hours later she was awakened by what she took to be dogs knocking over trash-cans. Then she heard gunfire. Leaping out of bed and pulling on some clothes, she went out to the dining room, where she found herself confronting a young man, Khmer, frightened-looking, pointing a pistol at her. Yelling “Don’t shoot!” she jumped back into the bedroom and ran to hide in the bathroom, from where she heard footsteps running upstairs (Dudman and Caldwell’s rooms were upstairs), then shots, then footsteps running back down. And then, for the next hour and a half, silence.

Then sounds: an enormous thud, a crash, broken glass, footsteps in the living room, footsteps going up the stairs, something heavy carried down, then up again. Then footsteps in her bedroom. The bathroom door opening slowly. One of the staff. “Don’t move,” he said, and went out again.

Forty-five minutes later their official minder arrived. He told her Dudman was fine, Caldwell was dead. She and Dudman were taken to see Caldwell’s body. He was lying on the floor in his pyjamas, blood on his chest. In the doorway was the body of a boy who looked like the young man Becker had seen earlier.

Becker and Dudman were taken to another house not far away, where they were questioned about what had happened. Dudman reported that he had woken to gunshots at 12.55. From his window he saw a file of half a dozen men running down the street then scattering between the houses. Going to a balcony off the hall he saw more men running. He knocked on Caldwell’s door and exchanged a few words with him. A man with a gun appeared in the corridor and fired a shot into the floor, Dudman jumped into his room and shut the door, and the man fired two shots through the door. Dudman thought he heard more shots but couldn’t be sure.

They asked the minder what had happened. He said the attackers were still at large, apart from two who had been captured and those (sic) who had been killed. (Dudman and Becker saw only one dead attacker). He also said there had been three armed guards at the guesthouse. Next morning there was a small service for Caldwell at the guesthouse, and Becker and Dudman departed with the coffin for Beijing.

So what happened? The Khmer Rouge blamed it on a Vietnamese plot, or rather a plot by Vietnamese sympathisers within the top circles of the KR. The two captured assassins (two guards from the guesthouse, it seems) made full confessions before their deaths. According to them only Caldwell was targeted, and the aim was to embarrass the leadership. The journalists were to be left alive to report the event to the world.

Becker accepts this, and thinks the aim may have been to discredit Ieng Sary, the KR Foreign Minister and the driving force behind the opening to the West, which was real enough if bizarre – in fact the Vietnamese had already crossed the border in force on 25 December and would arrive in Phnom Penh on 7 January.

An article by Andrew Anthony in the Guardian from 2010 gives more details. He tells how journalist Wilfred Burchett claimed to have seen a Cambodian report not long after Caldwell’s death stating that he “was murdered by members of the National Security Force personnel on the instructions of the Pol Pot government.” But scholar David Chandler reports meeting the translator of the meeting between Caldwell and Pol Pot, “who remembered a very pleasant exchange conducted in a spirit of enthusiastic agreement.”

Not, perhaps, that this gives any insight into the state of Pol Pot’s attitude to Caldwell. “Pol Pot, even when he was very angry, you could never tell” (said Ieng Sary years later). “His face… his face was always smooth. He never used bad language. You could not tell from his face what he was feeling. Many people misunderstood that – he would smile his unruffled smile, and then they would be taken away and executed.”

Or as Comrade Deuch, that born-again serial believer, once said, “Any theory or ideology which mentions love for the people in a class-based concept is definitely driving us into endless tragedy and misery.”

By Philip Coggan- Originally published in 2014