Around 4,400 years ago, a climatic event, combined with human development led to a massive shift across Asia. The Meghalayan period- named after an area of Northeastern India, is the last stage of the Holocene Period. The planet had gotten warmer, glaciers and tundra of the Ice Age melted away and sea levels rose.

Early civilizations had already sprung up across the new temperate zone- from the Eastern Mediterranean, the Fertile Crescent to the Indus Valley to the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers in China. For the first time in the age of man, a metal alloy- bronze- was being smelted and used widely from the Atlantic coasts across Eurasia to the Pacific.

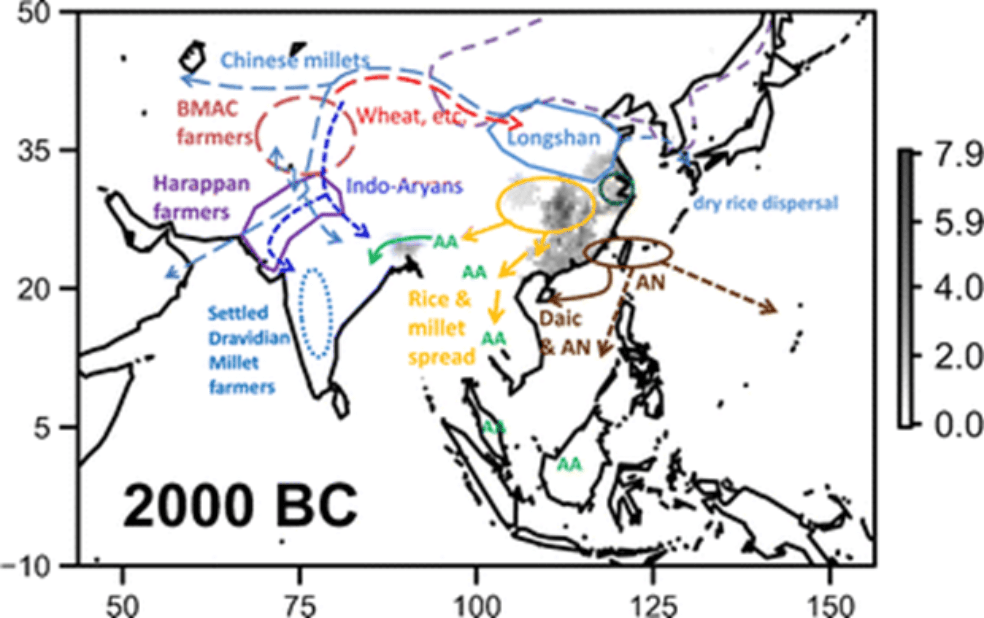

The beginning of the Megahalayan period 4,200 years ago, was ushered in by two centuries of drought, and mass exodus of peoples across the world, including Southeast Asia. It was also the era that widespread agricultural techniques in Asia- especially in rice cultivation- that began to move south and west, brought by migrating farming groups.

If DNA and linguistic studies are to be believed, some 4000 years ago a tribe of Mon-Khmer speakers set out from somewhere in mainland Southeast Asia heading west.

They finally settled in Northeastern India- in the hills of what is now the Indian state of Megahalaya- the same state that gives the geological period its name.

No records exist for the cause of this migration, only oral tradition that talks of a ’12-year journey’ that most likely took them north to the Himalayan range, perhaps as far as Tibet, before they settled in one of the world’s wettest environments.

Today the descendants are the major ethnic group in the state- known as the Khasi people. Their relative isolation, up until the arrival of the British, in a remote location, has left a fascinating linguistic and cultural legacy of one of the few surviving populations of prehistoric Southeast Asian migrations on the Indian sub-continent.

Origins

It is not certain where the Khasi people originated, or whether they came from fixed settlements or were semi-nomadic. It is likely they split with the Palaung group- another Mon-Khmer tribe presently numbering around 500,000 in Myanmar’s Shan State and the Chinese border region.

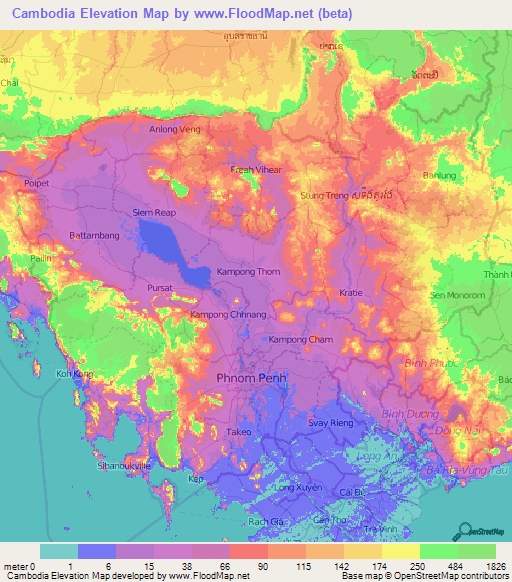

The Mon-Khmer speaking Neolithic tribes covered a vast expanse of mainland Southeast Asia, from what is now Myanmar to Laos. The geography of the region was much different, with sea levels reaching a peak of 4.5 meters above current levels. The map below shows the current elevation of the Mekong, after 19,000 years of gradual silt build up from Himalayan glacial run off. The Tonle Sap lake is only a mere 5,700 years old- and the constant changing course of the Mekong and Chao Praya rivers altered the landscape over thousands of years.

The Mon-Khmer tribes were not homogeneous, and even today, some 130 or so variants of Mon-Khmer language still exist. The vast majority, including Khasi, had no writing system, and later used neighboring script, such as Bengali or Burmese-and the Latin alphabet after contact with the British in the 19th century. The major exception being the ‘Cambodian’ or Lowland Khmer group- which developed a script heavily influenced by Pali, brought by Indian Brahman priests from about the middle of the first millennia.

One of the earliest accounts of Khasi culture was written by Major P. R. T. Gurdon, I. A., Deputy Commissioner Eastern Bengal and Assam Commission, and Superintendent of Ethnography in Assam, and was published in 1907 and although steeped in colonial attitudes, is a fascinating read (FULL E-BOOK available free here). He wrote, in a typical Victorian colonial manner:

“The people are cheerful in disposition, and are light-hearted by nature, and, unlike the plains people, seem to thoroughly appreciate a joke. It is pleasant to hear on the road down to Theriaghat from Cherrapunji, in the early morning the whole hillside resounding with the scraps of song and peals of laughter of the coolies, as they run nimbly down the short cuts on their way to market.

The women are specially cheerful, and pass the time of day and bandy jokes with passers-by with quite an absence of reserve. The Khasis are certainly more industrious than the Assamese, are generally good-tempered, but are occasionally prone to sudden outbursts of anger, accompanied by violence. They are fond of music, and rapidly learn the hymn tunes which are taught them by the Welsh missionaries.

Khasis are devoted to their offspring, and the women make excellent nurses for European children, frequently becoming much attached to their little charges. The people, like the Japanese, are fond of nature.

A Khasi loves a day out in the woods, where he thoroughly enjoys himself. If he does not go out shooting or fishing, he is content to sit still and contemplate nature. He has a separate name for each of the commoner birds and flowers. He also has names for many butterflies and moths. These are traits which are not found usually in the people of India.

He is not above manual labour, and even the Khasi clerk in the Government offices is quite ready to take his turn at the hoe in his potato garden.

The men make excellent stonemasons and carpenters, and are ready to learn fancy carpentry and mechanical work. They are inveterate chewers of supari and the pan leaf (when they can get the latter), both men, women, and children; distances in the interior being often measured by the number of betel-nuts that are usually chewed on a journey.

They are not addicted usually to the use of opium or other intoxicating drugs. They are, however, hard drinkers, and consume large quantities of spirit distilled from rice or millet. Rice beer is also manufactured; this is used not only as a beverage, but also for ceremonial purposes. Spirit drinking is confined more to the inhabitants of the high plateaux and to the people of the Wár country, the Bhois and Lynngams being content to partake of rice beer.”

Gurdon writes of an earlier hypothesis that the Mon-Khmer may originally have come from India and were driven east by Indo-Aryan tribes. However, the story of ‘the 12-year journey – khad ar snem pynthiah/kynthih’ (with 12 being an abstract number, simply meaning ‘many’), and the Himalayas being called ‘ki lum Makashang’- translating to ‘the mountain we walked around’, suggests otherwise.

He also talks of a Reverend H. Roberts, a missionary and a Mr. Shadwell:

“The origin of the Khasis is a very vexed question. Although it is probable that the Khasis have inhabited their present abode for at any rate a considerable period, there seems to be a fairly general belief amongst them that they originally came from elsewhere.

The Rev. H. Roberts, in the introduction to his Khasi Grammar, states that “tradition, such as it is, connects them politically with the Burmese, to whose king they were up to a comparatively recent date rendering homage, by sending him an annual tribute in the shape of an axe, as an emblem merely of submission.”

Another tradition points out the north as the direction from which they migrated, and Sylhet as the terminus of their wanderings, from which they were ultimately driven back into their present hill fastnesses by a great flood, after a more or less peaceful occupation of that district. It was on the occasion of this great flood, the legend runs, that the Khasi lost the art of writing, the Khasi losing his book whilst he was swimming at the time of this flood, whereas the Bengali managed to preserve his.

Owing to the Khasis having possessed no written character before the advent of the Welsh missionaries there are no histories as is the case with the Ahoms of the Assam Valley, and therefore no record of their journeys. Mr. Shadwell, the oldest living authority we have on the Khasis, and one who has been in close touch with the people for more than half a century, mentions a tradition amongst them that they originally came into Assam from Burma via the Patkoi range, having followed the route of one of the Burmese invasions. Mr. Shadwell has heard them mention the name Patkoi as a hill they met with on their journey. All this sort of thing is, however, inexpressibly vague.”

Tony Joseph, an Indian journalist also writes on the same questions, and suggests ancient rifts between the tribe in the best-selling book Early Indians: The Story of Our Ancestors and Where We Came From

“Tradition amongst the Pnars of Jañtia hills also has a story of u Sajar Ñangli who rebelled against the king of his time and left his land for good. It is believed that he led an exodus of his followers and walked towards the east.”

Khasi folklore has its own creation myth, where mankind originated in the ‘Ki Hynñiewtrep (“The Seven Huts”).According to mythology, U Blei Trai Kynrad (God, the Lord Master) had originally distributed the human race into 16 heavenly families (Khadhynriew Trep). However, seven out of these 16 families were stuck on earth while the other 9 are stuck in heaven. According to the myth, a heavenly ladder resting on the sacred Lum Sohpetbneng Peak (located in the present-day Ri-Bhoi district) enabled people to go freely and frequently to heaven whenever they pleased until one day they were tricked into cutting a divine tree which was situated at Lum Diengiei Peak (also in present-day Ri-Bhoi district), an error which prevented those on the ground access to heavens and trapped those in heaven forever.

These ‘Children of the Seven Huts’ are believed to have been the various geographically settled clans of the group; Khynriam, Pnar, Bhoi, War, Maram, Lyngngam and Diko- who share similar roots and culture, but whose dialects are almost unintelligible the others.

The Khynriam (or Nongphlang) inhabit the uplands of the East Khasi Hills District; the Pnar or Synteng live in the uplands of the Jaintia Hills. The Bhoi live in the lower hills to the north and north-east of the Khasi Hills. and Jaintia Hills towards the Brahmaputra valley, a vast area now under Ri Bhoi District. The War, usually divided into War-Jaintia and War-Khynriam in the south of the Khasi Hills, live on the steep southern slopes leading to Bangladesh. The Maram inhabit the uplands of the central parts of West Khasi Hills Districts. The Lyngngam people who inhabit the western parts of the West Khasi Hills bordering the Garo Hills display linguistic and cultural characteristics which show influences from both the Khasis to their east and the Garo people to the west. The last sub-group completing the “seven huts”, are the Diko, an extinct group who once inhabited the lowlands of the West Khasi Hills.

Language

The Khasi language shows connection to the Mon-Khmer of Southeast Asia, along with Tibeto-Burman, Palaung, and even some words similar to modern day Vietnamese and Thai- suggesting an ancient link between these groups.

Some examples are given (others comparing various Mon-Khmer languages were also recorded in Gurdon’s book):

| English | Khasi | Khmer | Viet |

| Tiger | Khla | Khla | |

| To fly | Her | Haer | |

| Belly | kpoh | Poh | |

| New | Thymme / thymmai | Thmei /thmai | |

| Year | Snem | Chnem | |

| Far | Jngai | Chngay | |

| Leaf | Sla / ‘la | Slaek | La |

| Fingers | Preamti (Pnar dialect) | Mreamdai | |

| Toes | Preamjat (Pnar dialect) | Mreamcheung | |

| Children | Khun,khon,kon | Kaun, kon | |

| Birds | Sim | Chim | |

| Eyes | Khmat/’mat | Mat | |

| Fish | Kha | Ca | |

| To weep | Iam | Yom | |

| Mother | Mei | Mdai | Me |

The Khasis live by nature, in one of the wettest environment on earth (the state capital Shillong is known as ‘Scotland of the East’). Traditionally they adopted the lunar month, u bynai, twelve of which go to the year ka snem. The following are the names of the months, the source is P. R. T. Gurdon, written at the beginning of the 20th century:

They have no system of reckoning cycles, as is the custom with some of the Shan tribes.

U kylla-lyngkot, corresponding to January. This month in the Khasi Hills is the coldest in the year. The Khasis turn (kylla) the fire brand (lyngkot) in order to keep themselves warm in this month, hence its name kylla-lyngkot.

U Rymphang, the windy month, corresponding with February.

U Lyber, March. In this month the hills are again clothed with verdure, and the grass sprouts up (lyber), hence the name of the month, u Lyber.

U Iaiong, April. This name may possibly be a corruption of u bynai-iong, i.e. the black moon, the changeable weather month.

U Jymmang, May. This is the month when the plant called by the Khasis ut’ieu jymmang, or snake-plant, blooms, hence the name.

U Jyllieu. The deep-water month, the word jyllieu meaning deep. This corresponds to June.

U náitung. The evil-smelling month; when the vegetation rots owing to excessive moisture. This corresponds with July.

U Jyllieu. The deep-water month, the word jyllieu meaning deep. This corresponds to June.

U náitung. The evil-smelling month; when the vegetation rots owing to excessive moisture. This corresponds with July.

U’náilar. The month when the weather is supposed to become clear, synlar, and when the plant called ja’nailar blooms. This is August.

U’nái-lur. September. The month for weeding the ground.

U Ri-sáw. The month when the Autumn tints first appear, literally, when the country, ri, becomes red, saw. This is October.

U’nái wieng. The month when cultivators fry the produce of their fields in wieng or earthen pots, corresponding with November.

U Noh-práh. The month when the práh or baskets for carrying the crops are put away (buh noh). Another interpretation given by Bivar is “the month of the fall of the leaf.” December.

The Khasi week has the peculiarity that it almost universally consists of eight days. The reason of the eight-day week is because the markets are usually held every eighth day. The names of the days of the week are not those of planets, but of places where the principal markets are held, or used to be held, in the Khasi and Jaintia Hills. The following are the names of the days of the week and of the principal markets in the district.

Khasi is also unique among Mon-Khmer language groups, as it has a pervasive gender system. There are four genders in this language:

u masculine

ka feminine

i diminutive

ki plural

Humans and domestic animals have their natural gender:

ka kmie `mother’

u kpa `father’

ka syiar `hen’

u syiar `rooster’

Rabel (1961) writes: “the structure of a noun gives no indication of its gender, nor does its meaning, but Khasi natives are of the impression that nice, small creatures and things are feminine while big, ugly creatures and things are masculine….This impression is not born out by the facts. There are countless examples of desirable and lovely creatures with masculine gender as well as of unpleasant or ugly creatures with feminine gender“

Though there are several counterexamples, Rabel says that there is some semantic regularity in the assignment of gender for the following semantic classes:

| Feminine | Masculine |

| times, seasons | |

| clothes | reptiles, insects, flora, trees |

| physical features of nature | heavenly bodies |

| manufactured articles | edible raw material |

| tools for polishing | tools for hammering, digging |

| trees of soft fibre | trees of hard fibre |

The matrilineal aspect of the society can also be seen in the general gender assignment; all central and primary resources associated with day-to-day activities are signified as Feminine; whereas Masculine signifies the secondary, the dependent or the insignificant.

| Feminine | Masculine |

| Sun (Ka Sngi) | Moon (U Bnai) |

| Wood (Ka Dieng) | Tree (U Dieng) |

| Honey (Ka Ngap) | Bee (U Ngap) |

| House (Ka Ïing) | Column (U Rishot) |

| Cooked rice (Ka Ja) | Uncooked rice (U Khaw) |

Culture

Khasi culture is matrilineal- with woman inheriting land and property- in common with other, smaller Mon-Khmer tribes, such as the Tampuan of Northeastern Cambodia and the neighboring ethnic group in Megahalaya- the Tibeto-Burman Garo people.

There has been considerable debate among historians and anthropologists over whether- or to how much of a degree- lowland ‘Cambodian’ Khmers have in the past been matrilineal.

A Khasi heiress is known as a Ka Khadduh, and any man marrying her must go to live his wife’s mother until her death.

To quote Gurdon again: The Khasi saying is, “long jaid na loa kynthei” (from the woman sprang the clan). The Khasis, when reckoning descent; count from the mother only; they speak of a family of brothers and sisters, who are the great grandchildren of one great grandmother, as shi kpoh, which, being literally translated, is one womb; i.e. the issue of one womb. The man is nobody. If he is a brother, u kur, a brother being taken to mean an uterine brother, or a cousin-german, he will be lost to the family or clan directly he marries. If he be a husband, he is looked upon merely as a u shong kha, a begetter.

The Khasi inhabited regions are also famous for their monoliths, remarkably similar to the ancient standing stone sites found around the British Isles and areas of France. Like their western counterparts, these sacred stones were quarried far from the site and took considerable labor to move and erect. Unlike Stonehenge and other European Neolithic sites, these are mostly dated in the hundreds of years, rather than by the thousands.

These sites are believed to be commemoration points, rather than gravestones- with upright ‘menhirs’ representing male spirits and ‘dolmen’ table stones laid flat representing females.

There are numerous designs and uses, which are explained in more detail by Major Gurdon. Although they are still a popular sight around Megahalaya, many more were knocked down in the great earthquake of 1897.

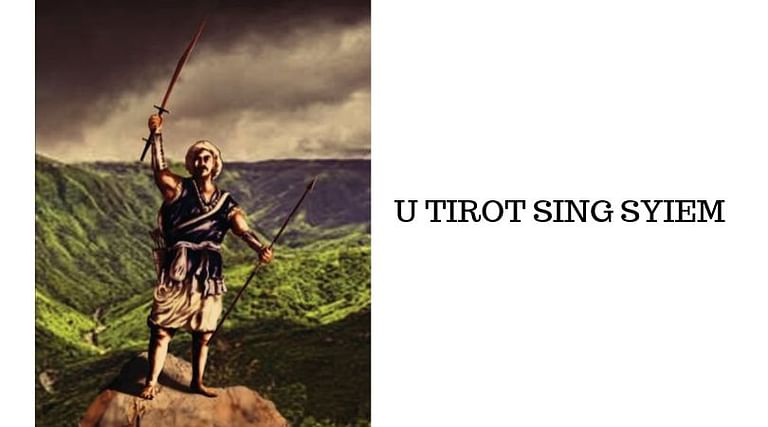

The British

The British East India Company had knowledge of the tribes in by the late 18th Century, and came into direct contact with the Khasi in 1823, after capture of Assam. A guerrilla war lasting 4 years was fought between the British and a Khasi tribal leader U Tiroth Sing between 1829-33.

The British used the typical colonial mix of sepoys, technology, brutality and bribery, bringing the area inhabited by the Khasis into part of the Assam province, after the Khasi Hill States (which numbered around 25 kingdoms) entered into a subsidiary alliance with the British.

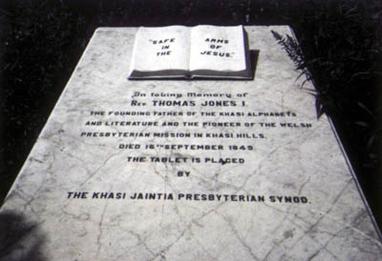

A Welsh missionary named Thomas Jones (24 January 1810 – 16 September 1849) worked among the Khasi people in Meghalaya and Assam in India and of Bangladesh. As a carpenter, he learned the language while training local men and began preaching the Bible in Khasi with was said to be incredible fluency during the 1830’s. He also translated books from Welsh into Khasi and recorded the Khasi language in Roman script .

The inscription on his gravestone calls him “The founding father of the Khasi alphabets and literature”.

In 2018, the state government announced that June 22, the date of Jones’s arrival at Sohra, would be celebrated as “Thomas Jones Day” every year in the state of Meghalaya.

Modern Times

The Khasi people form the majority of the population of the eastern part of Meghalaya, numbering around 1.5 million- the state’s largest ethnic community, with around 48% of the population of the state. Smaller populations are found in Assam state and in Bangladesh.

Around 85% of the Khasi people identify as Christians, with around 2% following Islam. Others still continue the traditional beliefs of Khasi culture.

The preservation of Khasi culture, along with the linguistic studies into its evolution from old Mon-Khmer gives us an incredible look into the peoples of Southeast Asia. The Khasi people have the status of a ‘Scheduled Tribe) under the Constitution of India.

Sources include: Wikipedia, Major Gurdun, The Shillong Times, Dr Valentine B Sohtun, Tony Joseph, James’ Khasi friend in Singapore, Meghalaya State records, The People of Northeast India

Mei (Mother): In Khmer we call Mday or Me or Mae or Mak.

Sla / ‘la (Leaf): In Khmer, some people tend to omit sound “s”, for example: Sleuk (leaf), they can say “leuk”