Conflict between Siam and Vietnamese lords raged over control Cambodia throughout the 18th Century before the kingdom agreed to become a French protectorate state. The following article is sourced from Catholic church records, a few old maps, Father François Ponchaud, Phnom Penh Post archives, previous articles from which the sources have been forgotten and the excellent King Norodom’s Head, by Steve Boswell (not this History Steve). Special thanks to the man B from Phnom Penh Past for clearing up a few of the trickier details.

I’ve tried to be as accurate as possible, but many of the sources disagree- but what is a year or three between this and that happening? Correspondence between Europe and Asia took several months each way. Most records before the printed word appeared-belatedly in comparison with most of the world at the time- were made on fragile handwritten palm leaf papers, and of course, the mass destruction of all forms of knowledge by the Khmer Rouge regime.

If anything is inaccurate, please get in touch via CNE and efforts will be made to rectify.

The Portuguese Remnants

In 1686, a Swiss missionary named Jean Genoud had founded a church and hospital on land granted by the king in Ponhea Leu- close to the capital of Oudong- where a Father Louis, a Portuguese Franciscan friar and doctor tended to the sick.

Both church and hospital were destroyed somewhere around the turn of the 17th century in a Vietnamese attack on Oudong. The buildings were razed and villagers massacred, with both the Europeans wounded and left for dead. Father Louis later died of his wounds, but Genoud managed to recover and escaped to Burma.

The remaining ‘Portuguese’ Catholics- whose numbers were now only in the hundreds- must have appeared a strange ethnic mix by this time after a century and a half of settling near Oudong. The Dutch had previously described how Europeans, Japanese, Filipinos and ‘black’ Portuguese from around the empire were living side by side close to Malay, Chinese and Khmer villages, so one can only imagine the features of children that must surely have been born from romantic trysts and inter-marriages.

This tiny religious minority suffered a major schism by the turn of the 18th century- between a clan known as the Soarez, who took religious orders from the church in Lisbon, and the smaller Diaz clan, who looked to Rome.

An example of how much these groups hated each other was recorded in 1718, after a Japanese Priest named Michel Donno was sent to Ponhea Leu to serve the congregation. To begin with he took the side of the Soarez group, but was ordered to join the Diaz clan on orders from the Vatican. To protest this ecumenical shift, members of the Soarez faction cut off the poor friar’s foot one night- he died from loss of blood soon after.

By 1734 the Soarez clan had moved to a new village nearer Oudong, but animosity between the rival sects continued for half a century until both communities were destroyed by another Vietnamese invasion in 1784.

L’église d’Indochine

As French influence over Southeast Asia grew by the middle of the 19th Century, the Catholic Church was at the forefront, even as ideas of secularism and separation of church and state grew back in the republic.

In Vietnam, the Catholic Church was all but obliterated during the Tây Sơn rebellion, French Vicar Apostolic Pigneaux de Behaine forged an alliance with the eventual victor of the long civil war, Nguyen Anh.

After Nguyen’s victory in 1802, he promised protection for missionary activities, but local officials quickly began to complain against Catholicism and the political role they had in Vietnamese afairs. Tolerance continued until the death of the emperor, when new emperor Minh Mang- a hardline Confucian- took the throne in 1820.

In 1831 the emperor passed new religious laws, with Catholicism officially prohibited. In 1832, a largely Catholic village near Hue, was uprooted, with the entire community being incarcerated and sent into exile in Cambodia.

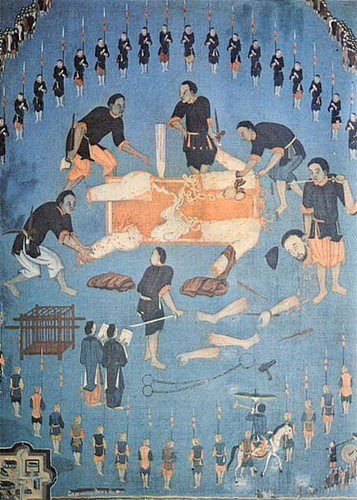

Over the next years, until Minh Mang’s death between 130,000 and 300,000 Vietnamese Catholics were killed, mostly from the south, in rebellions and purges. Among them were several prominent European missionaries- who suffered horrendous tortures and methods of execution, including being branded on the face with the words “tà đạo” (邪道, “Left (Sinister) religion”), having limbs removed one by one, and the Chinese practice of slicing, or ‘death by a thousand cuts’.

Of these, 117 were later canonized as ‘the Martyrs of Vietnam’, with their memorial day on November 24.

As between Siam and Vietnam wrestled over control of Cambodia, the Vietnamese catholic community grew in the less governable places- with semi-nomadic communities taking to the waters along the vast and sparsely populated swamps, lakes and tributaries of the lower Mekong river system. Some of these predominantly ethnic-Vietnamese ‘floating villages’ still survive.

In the west, missionary Jean-Baptiste Pallegoix had forged better relations with the Siamese monarch, and became became vicar apostolic of Eastern Siam (which included the ceded Cambodian territories of Siem Reap and Battambang) on 10 September 1841. He became a close friend of pro-western King Mongkut (Rama IV) and the pair were said to often engage in long discussions and debates.

In 1850 (another source says 1848), as the devastating wars calmed, the Holy See established the Apostolic Vicariate of Phnom Penh, covering all the Kingdom of Cambodia, entrusting it to the care of the priests of the Paris Foreign Missions Society.

This society, known by the French acronym MEP (Société des Missions étrangères de Paris) was also active in the Vietnamese provinces of what was then Cochinchina. Attacks on these missionaries by the local lords provided useful justifications for French military incursions, leading first to three southern provinces becoming the French colony of Cochinchina in 1864. The French quickly expanded to control the whole of what is now modern Vietnam, with the Protectorate of Cambodia (1863) being incorporated into the French Indochina Union (1887), and later Laos (which became a French protectorate in 1893).

The First Bishops

By 1790, a small number of Catholics had settled on the outskirts of Battambang town at around the same time that the Siamese rule of Phra Tabong began. The reasons for this move are not clear, but it is likely they were escaping the wars, persecution and the sectarian split in other parts of the kingdom- and sought the relative security and the protection offered by the newly installed governor Chaophraya Aphaiphubet (also known as Baen) in the Siamese dominated northwest. Other small groups of Catholics had also settled in the provinces of Siem Reap and Kompong Thom.

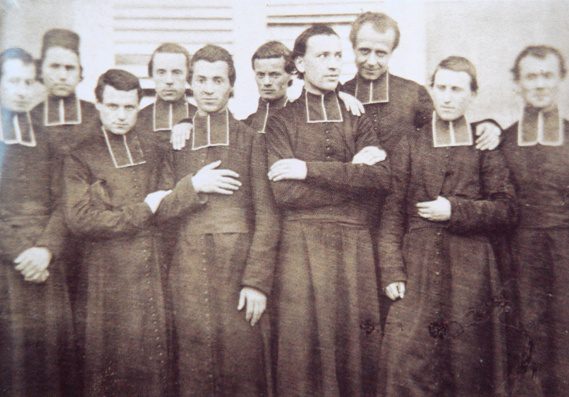

Jean-Claude Miche of the MEP left Paris on 27 February 1836 and later arrived in Bangkok after first visiting Cochinchina briefly. In Siam he studied the Khmer language under Cambodian Christians who had fled the wars across the border. In 1838, he moved into Cambodia, traveling with a fellow missionary, Pierre Duclos, to Paknam by boat and then through the jungle to Battambang on foot. They arrived in Battambang in time to celebrate Midnight Mass on 25 December 1838.

Miche and Duclos found a congregation of mostly Chinese merchants and mixed-race descendants of Portuguese, but the following year a rebellion headed by prince Ang Em caused the population to flee. The missionaries left Battambang on 7 January 1840 for Bangkok, arriving on 2 February 1841.

Miche then traveled by boat to central Vietnam, where he was captured and sentenced to death over his efforts to convert Montagnard tribespeople. After a petition from Louis Philippe I of France to Emperor Thiệu Trị, he was freed.

After his incarceration returned to Cambodia after the rebellion had cooled, moving to Ponhea Leu to attempt to rebuild the church there, He was appointed apostolic vicar of Cambodia in 1850 (the Cambodian mission being split from the Vietnamese regions), and was put in charge of evangelizing Laos. He attempted to visit a pair of French priests had been living among the hill tribes in Stung Treng province, but the journey proved too difficult. By 1853 he reached the Laotian areas along the border and found a people even less willing to convert than the stubbornly Buddhist Khmer.

Miche too became involved in politics and befriended King Ang Duong, failing to convince him to take up the offer of French protection. After Ang Duong’s death in 1860, he organized forces for the elected King Norodom in the civil war which followed. Having gained the trust of Norodom, the priest was involved in persuading the king to accept the French Protectorate.

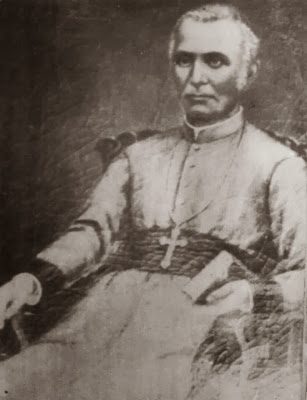

He left his position in 1869, after he authored a Latin-Cambodian dictionary and published a number of his letters in the Annales de la propagation de la foi (1863). He spent his remaining years as a missionary and died in Saigon on 1 December 1873. There were two successors before the end of the century; Marie-Laurent-François-Xavier Cordier, M.E.P., appointed in 1874 – until his death on 14 August 1895 (who despite over 20 years in the position, has very little written about him) and Jean-Baptiste Grosgeorge, appointed on 28 January 1896 and who died on 1 March 1902.

Grosgeorge arrived in Cambodia in 1870, and studied the Khmer language at the church in Russey Keo. After a long stint in Vietnam, he returned to Phnom Penh and encouraged his fellow missionaries to preach in Khmer, and worked on a new Cambodian-French dictionary. Finding that there were no Cambodian characters available for printing presses, he reportedly had them cast at the Mission’s own Nazareth printing press house in Hong Kong- therefore bringing the printed word to the kingdom. This initially caused concern for the conservative and literate Khmer elite, who believed that writing was best left to monks, who had transcribed mostly religious texts onto palm leaves, sasatra, for centuries.

A New Capital, Old Grounds

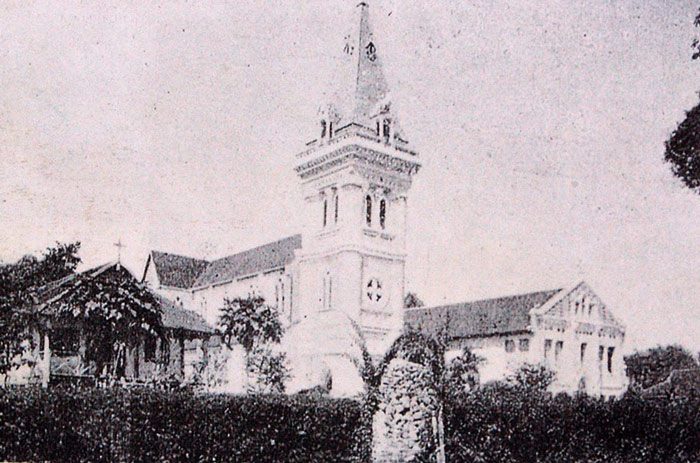

In 1865 or ‘66, Catholics, along with most of the population around Oudong, were ordered to leave and resettle in the new capital under development in Phnom Penh. They were given land Russey Keo, an area where a large number of Vietnamese refugees had also given granted rights to live. The community that stayed at Ponhea Leu soon joined them after the area was burned down in another rebellion. Sources say the church was built in 1863 (which would have been around the same time the Vietnamese were permitted to settle), but the records are not entirely accurate-another say the building was finished in 1866.

“Preah Meada” (loosely translated to ‘Holy Mother/Lady’) was situated in an area then known as Hoalang, or Hoalong-perhaps a reference to the Dutch settlement of the 1600’s- and became the center of Catholicism in Cambodia for the rest of the century. The church was later rebuilt in 1899, serving a mostly Vietnamese congregation with a few local converts and Chinese.

In 1881, the Sisters of Providence of Portieux- a devout sect of nuns sworn to poverty- opened a house in Phnom Penh on the Chroy Changvar peninsula from at least 1901, looking a map records. The Chroy Changvar site was later developed and became a Carmelite convent and church sometime around 1920- Carmel Notre-Dame d’Esperance. Around the same time a church was built south of Kralanh (cover photo) on what is now the border of Banteay Meanchey and Siem Reap provinces-one of the handful of 19th century church buildings that still survive.

In 1905, two Sisters of Providence of Portieux went to Battambang and opened an orphanage and a hospital on the outskirts of the town. A church was built at around that time- later destroyed by the Khmer Rouge.

A Question of Converts?

The French preferred to use Vietnamese as their functionaries and administrative bureaucrats- much in part due to better education from the larger urban populations compared with the Cambodians- most of whom had, at best a short schooling in Pali by local monks (boys only). The growing number of Vietnamese Catholics would be given the best positions, in both Vietnam and Cambodia, and so the Vietnamese Christian community grew even larger, and politically powerful, at the beginning of the 20th century.

After half a century of French rule, the Catholic Church- which held a Christian monopoly over Indochina- had failed to make any real inroads when converting the predominantly Buddhist population.

French missionary and historian François Ponchaud, author of La cathedrale de la riziere: 450 ans d’histoire de l’eglise au Cambodge, estimates that shortly before the First World War there were 36,000 Catholics in Cambodia: 32,500 Vietnamese, 3,000 Khmers and 500 Chinese from a total population of around 1.5 million.

One reason for this could be the Vietnamese and Chinese Buddhist devotion to Quan Âm (in Vietnamese) or Guanyin in Chinese- the Chinese goddess of mercy and the Chinese form of the Indian bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.

The similarities between the goddess and the virgin Mary were certainly noted by early missionaries across eastern Asia, and iconography even began to change more towards the European ideals when trade between the east and west flourished from the 17th century.

The Goddess is unknown in Theravada Buddhism, although neak ta Ma Sar– a form of ancient Hindu goddess of war and protector of the weak Durga Devi Mahisasuramardini, was worshipped until recently in Cambodia, but with offerings of blood sacrifice, rather than compassion.

By the turn of the 20th century, French power seemed firmly rooted in her Asian colonies. The city of Phnom Penh, no more than a small settlement on the Mekong floodplains, had grown to around 50,000 inhabitants in only 30 years. The first iconic buildings of ‘Paris of the Orient’ had already been completed, and grandiose plans for more development in the new age of science and technology were underway. And, although the church had failed to make any real progress in evangelizing the Cambodian people, seemed likely to continue to have an important role in the affairs of the state.

Wars, both in Europe and Asia, rising nationalism and anti-colonialist sentiments, along with a radical philosophy learned in Paris and adapted for Indochina, would have a devastating impact in the next century to follow.