Whilst enjoying a coffee and minding my own business recently, a youngish Cambodian man struck up a conversation. He asked me a question that has come up before- “Are you Christian?”. I answered in the negative, and tried to explain as a keen amateur follower of history, it would be difficult to adopt a doctrine that has, for a fact, been altered so many times to suit social and political agendas of the ages. This went over his head, so I asked his question back to him. He replied “50 percent” – meaning he still carries out his Buddhist duties, but also sometimes attends a local church meeting.

This got me thinking- Cambodia- at least up until the mid-20th century- has been known for religious tolerance and mishmash of belief systems. The animism of the ancient kingdoms can still be seen in spirit houses, Nek Ta statues, the occasional ‘magic tree’ and dark rituals. Hinduism and Buddhism lived side by side for centuries, until amalgamating into the Theravada sect.

Likewise, mass Chinese emigration into Cambodia brought the philosophy of ‘the three teachings’- combining Taoism, Confucianism and Buddhism.

An average Cambodian (with distant Chinese ancestry) home will have a spirit house outside, a Buddhist mural or image on a wall inside and a small Chinese Taoist alter/shrine in the main room.

Christianity- despite half a millennia of missionary efforts still remains the ‘Barang’ religion. With a plethora of church organizations active in the Kingdom, Christianity is slowly becoming more popular among the young and moving away from its more traditional congregations of ethnic-Vietnamese.

So, deep into old notes and Google research I headed, to look into the history of Christianity in the region- trying to steer clear of theological debates-but admittingly subjective at times. Steve

The Early Missionaries- And Siamese Legend?

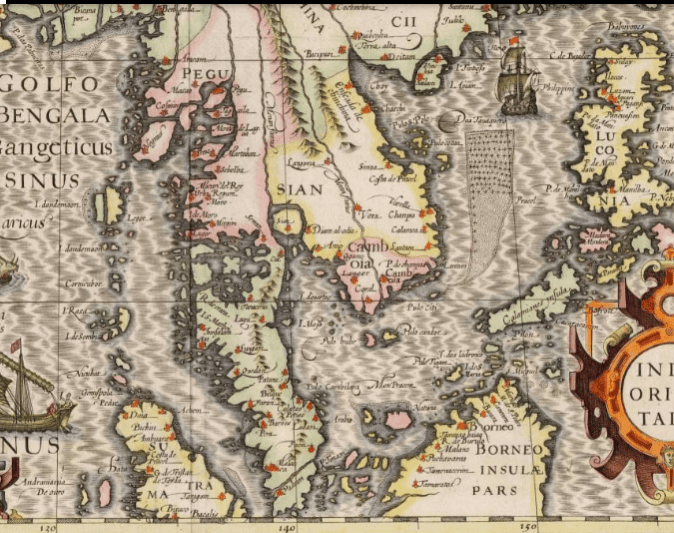

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to arrive in Cambodia in 1511, with messengers from Admiral Afonso de Albuquerque, one of the greatest naval strategists of the age. De Alberquerque had recently taken Goa and Malacca for the Portuguese crown and followed the 3-fold strategy of spreading Christianity, combatting Islam and forging a Portuguese-Asian empire to dominate the spice trade.

Yet, in around 1510, Ludovico di Varthema, an Italian merchant visited the Siamese kingdom of Ayutthaya (reaching the upper part of the Malay Peninsula, now modern day Myanmar). There he was met by two Chinese-Christian guides who said they were from Sarnau (which some believe is Shahr-i Naw, the Persian name for Ayutthaya- translated in both Persian and Siamese languages as ‘The New City’).

They told him that there were many Christians in Sarnau, even “great lords”, that they were white men and that they owed their allegiance to the Great Khan of Cathay. Varthema also recorded that the King of Pegu (Burma) employed 1,000 Christians soldiers recruited from the Ayutthaya Kingdom and that they wrote their script from right to left. These accounts were most likely exaggerated to impress the Europeans, but it is possible that these first Christians in Thailand, and likely some in Cambodia, given the overlapping borders, were the descendants of near-Eastern Nestorians who fled China after the fall of the Yuan Dynasty in 1368. They would have most likely used the Syriac script.

Although no evidence can be given of this group other than what was related to di Varthema, reports of Nestorian missionaries visiting the kingdom of Annam, Northern Vietnam in the 10th Century exist- and the Nestorians did travel east along the Silk Route from the 7th to 9th centuries- the first being a monk Alopen, who arrived in the Chinese capital of Chang’an in 635. Senior members of the church later held high positions in 13th and 14th century Mongol Courts- so it would not take a great leap of faith to presume that there was some early Christian presence in the sprawling territories of the Angkorian Empire, and perhaps it’s huge and cosmopolitan capital.

Trade certainly existed between the Mediterranean and the pre-Angkor kingdoms of Funan and Chenla, with archeological finds discovering Greek earthenware and Roman coins dating back to the 2nd Century- giving another possible route these mysterious group- described to the Italian as ‘white as he’.

Readers forgive me while I have a minor, and uncharacteristic, ‘Graham Hancock’ moment: The first Europeans to view the ruins of Angkor in the early 17th Century theorized that the great moments were built by Alexander the Great, or the ‘Chinese Jews’. Was this simply a case of early colonial attitudes in the disbelief that the Khmer people (viewed as primitive) could have built the impressive temple complexes? Or had they too heard about these ‘white soldiers’ with their strange writing style? Syriac- the alphabet of the Nestorian church- is closely related to Hebrew. Okay, back to more realistic accounts-at least no mention of aliens was made.

The first Christian missionary to begin work in Cambodia was Dominican Friar Gaspar da Cruz, who landed in 1555. The Friar, although promised that the region would be a favorable place to preach the word of God, quickly found out his work was little more than a ruse to attract more Portuguese ships.

After a year the missionary gave up, according to Jesuit missionary Luís Fróis. “he wasn’t able to spread the word of God and he was seriously ill… he quickly left the region without doing much and not baptizing more than a heathen that [he left] in the grave”.

In the decades that followed, it was the Spanish that became the dominant power in Southeast Asia.

Commerce, Conflict & Christianity- The Spanish Protectorate

Miguel López de Legazpi’s expedition arrived in the Philippines on February 13, 1565, from Mexico. He established the first permanent settlement in Cebu, and the islands- named after King Phillip II- quickly became under the control of the Spanish crown and Catholic church.

Phillip, son of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, was a staunch Catholic whose religious fervor was intertwined with his territorial ambitions across his huge empire

Phillip, who became king of Portugal, allowed a force of Spanish and Portuguese, along with Filipino and Japanese mercenaries and missionary priests to become involved in a succession of wars with Khmer factions and the Siamese. The Spanish-Cambodian war of 1593-1597 intended to Christianize Cambodia and install a puppet king on the throne.

Pivotal to these efforts were a pair of adventurers/rogues; a Spaniard named Blas Ruiz de Hernán González and a Portuguese explorer Diogo Veloso, who had befriended Satha I, a king who abdicated in favor of his son Chey Chettha in 1584.

READ ABOUT THEIR INCREDIBLE TALE HERE

Following the fall of Longvek to Ayutthaya in 1594, a Thai prince named Preah Ram I was installed as the new monarch of Cambodia, and the former royal family fled north.

Seemingly unperturbed, the Spanish once again returned from their Philippine colony, along with missionary monks and mercenaries, with the offer to resolve issues over the Cambodian successions and opening trade.

There were several outbreaks of violence involving the ethnically and religiously diverse merchant classes- made up of Chinese, Malays, Chams and others from far flung shores who had set up business in Longvek.

Some sort of uprising against the European presence began, which ended with the killing of hundreds of Chinese merchants and the usurper king Preah Ram I at the hands of the Spanish.

The young son of the now dead former king, who had been living in exiled in Laos, was returned and put on the throne by the Europeans, who were granted a protectorate in the areas of Takeo and Prey Veng.

Trouble continued to brew, and in 1598 the Spanish fleet was ambushed by a well-organized group of Malay, Cham and Chinese on the Mekong, and all but annihilated.

The Philippines Governor Pérez Dasmariñas refused to send reinforcements, but authorized a group of volunteers to travel to Cambodia in a donated ship. A Dominican friar Alonso Jiménez, was also sent to Longvek with a contingent of merchants interested in establishing the church and business.

Not to be outdone, Blas Ruiz took advantage of the situation and went to court with a forged letter from the governor in Manila, demanding that the Cambodian king paid for the losses and to give over a tract of land for the construction of a fortress.

The boy king, who had from a young age become fond of European wine, was drunk and remorseful and authorized the construction of the fort.

While the new Spanish contingent were on the ground finalizing the preparations to begin the construction of the new fort, Malaysian mercenaries assaulted their camp. The boy king was also killed by rebellious Khmers.

The Spaniards fought back, and in reprisal assaulted the capital, butchering the civilian population of Malays, Chinese, Khmer, Siamese and Laotians in cosmopolitan Longvek.

Fearing the construction of a Spanish fortress, which would make the Europeans near invincible behind stone walls and artillery, a coalition of the Asian communities formed together, armed themselves and killed all the Westerners in the city, both military and religious, along with the Japanese Christian and Filipino allies.

Accounts say only one Spaniard and a handful of Filipinos survived the slaughter.

The Spanish protectorate in Cambodia was formally abolished in 1600, by which time Phillip II was dead and his former empire shrinking and bankrupt from decades of wars across every continent known at the time.

In Europe, breakaway provinces had rebelled against the Spanish crown and formed the Dutch Republic. The Dutch Calvinists of post-reformation northern Europe valued science and technology-and vitally hard-earned wealth- over the hierarchical dogma and forced conversions of the inquisition-era Roman Catholic church states.

Profits Before Proselytizing- Enter The Dutch East India Company

Formed in 1602, the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOA), known in English as the Dutch East India Company, began to both trade with Asia and wage war against the Spanish and Portuguese in the region, while the Wars of the Spanish Succession raged back in Europe.

The Dutch established trading bases with Japan, who after experiencing Portuguese and Spanish missionaries, and seeing the mass conversion of the Philippines to Catholicism, had banned Christianity and foreign powers from the islands. Many Japanese Christians were forced underground, or exiled and forbidden from returning.

More interested in capital than Christ, the Dutch were granted limited, but exclusive trading rights with Japan- the only other merchants allowed to do business were Chinese.

Japan had precious metals-silver and copper- but lacked natural resources such as timber and had a taste for luxury items such as ivory and animal hides.

With the Spanish firmly embedded in the Philippines and Malacca (until seized by the VOA in 1641) under Portuguese control, the Dutch headed to Cambodia. There, along the Mekong, they found communities of Portuguese and ‘black’ Portuguese- subjects from across the vast empire- Brazil, Angola, Goa and other places- and villages inhabited by exiled Japanese Christians who had fled the anti-Christian purges in Japan and across other parts of Asia.

In Vietnam, Jesuit missionaries had converted over 6,000 people between 1627-30. The missionaries, including Francisco de Pina, Gaspar do Amaral, Antonio Barbosa, and de Rhodes developed the alphabet for the Vietnamese language, using the Latin script with added diacritic marks which is used today- known as the chữ Quốc ngữ (literally “national language script”).

The power of the Jesuits worried the local lord Trịnh Tráng of Tonkin, who expelled them in 1630- with some no doubt crossing over into Cambodia where there was more tolerance. The Japanese Christian community were also expelled from Hoi An in 1639, after a revolt against the local lords, increasing their numbers along the Cambodian Mekong.

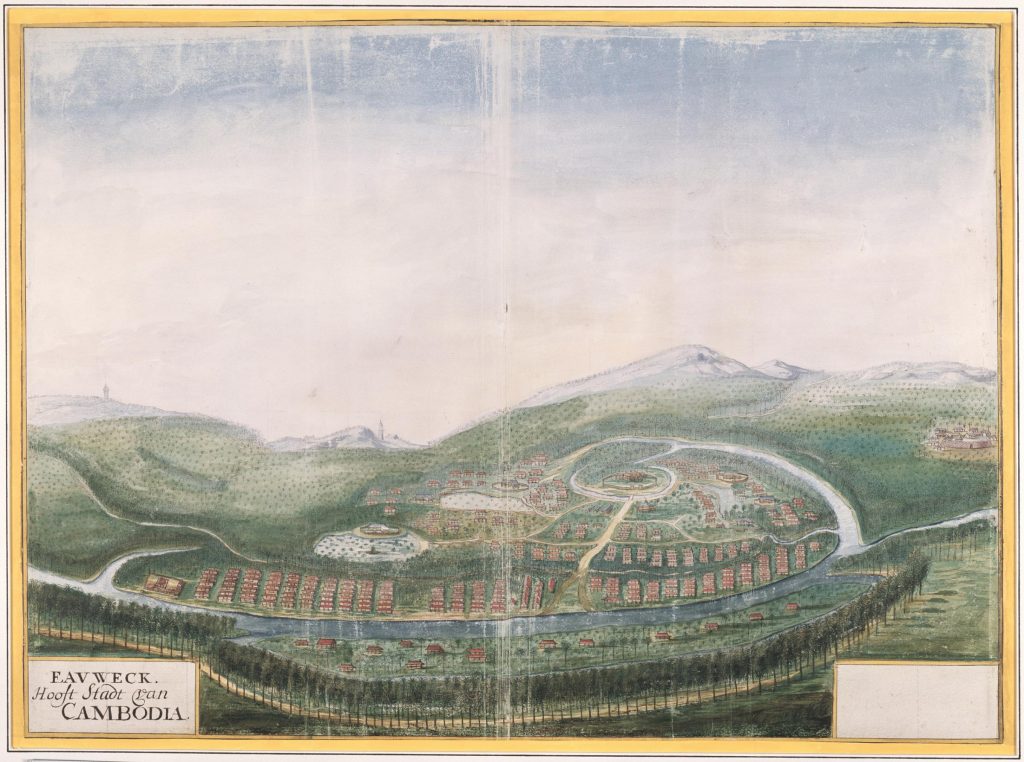

By 1637 the VOA, based in Batavia (Jakarta), had established a sizeable trading post around 20 km south of the new royal capital at Oudong, in the same area as the Portuguese and Japanese. To begin with, relations between the communities were, on the surface at least, peaceable.

The Dutch would have had some church presence with either pastors or lay clergy performing certain rites, such as worship and funeral services for their own brethren, but, like the VOC in Batavia, had little interest in upsetting their business over religious ideals. The theology of the Dutch Reformed church at the time was opposed to the mass baptism adopted by Catholic missionaries, and during the 17th century the church had very little impact on the local Muslim, Hindu and Buddhist cultures they encountered.

The peace was broken between all the major ethnic and religious groups in Cambodia- Buddhist, Islamic, Catholic and Protestant- in 1642.

A palace coup erupted when Ponhea Chan (also known as Ramathipadi I) murdered his brother-in-law Ang Non I and seized the throne with the help of Malay mercenaries. He then converted to Islam and took the name Sultan Ibrahim.

Records do not record how unpopular this was among the Buddhist population, but in turn, the Portuguese and Japanese Catholics- no doubt serving their own interests, put aside centuries of animosity toward the Islamic faith and gave support to the new King to drive the Dutch out of Cambodia.

The turning point seems to be after the Dutch found that Portuguese traders, with the consent of the new court, had been using Chinese junks to smuggle goods to Japan- in contravention to the trade deal the VOA had, and breaking the embargo placed by the Japanese.

This led to the Cambodian-Dutch war of 1643-44, which resulted in the Dutch being expelled from the kingdom.

Troubles With The Neighbors

The Muslim king’s reign lasted for some 15 years- a respectable length of time on the throne for a monarch during Cambodia’s ‘dark ages’- before a Vietnamese army invaded Cambodia, deposed him, and imprisoned him Quảng Bình in 1658. He died in the next year, probably killed by Vietnamese or died of disease.

The 18th century was devastating for Cambodia as wars raged between the Siamese and Vietnamese across the kingdom. The communities of Portuguese and Japanese Catholics most likely suffered during this period, along with the rest of the population, or gradually assimilated as links to their own national heritage became more distant.

However, the main parties in the long conflicts were also opening up to foreigners and Catholic missionaries.

The first French arrived in Siam in 1662. They had arrived overland from the middle east to avoid the Portuguese at sea, as the Portuguese had the ‘Padroado’, an agreement from the Vatican granting the kings of Spain and Portugal the right to send missionaries abroad.

In Ayutthaya they found a small band of Portuguese and Spanish settled in “Campo Portugués” on the banks of the river. The French were shocked to see the religious leaders, many among them Jesuits, being active in the court of Siam and doing business, which was contrary to the Papal agreement.

They quickly found themselves at loggerheads with their religious brethren and at one point Bishop Lambert de la Motte, the leader of the mission was forced to seek shelter with Dutch protestants after an assassination attempt.

At first the Siamese allowed the French to practice- as long as they did not use either the local language or the sacred Buddhist Pali- and were seen by the royal court as a useful countenance to the increasingly powerful Dutch.

After becoming involved with politics, going so far as to try to convert the Siamese King Narai, the French were expelled from the kingdom in the late 1680’s, and all diplomatic relations stop until 1856.

Bishop Laneau and all the missionaries and seminarians were thrown into cages and held hostage for 21 months and all Christian preaching was forbidden. Six French missionaries who remained in Siam were allowed a small measure of autonomy again in 1690 after swearing an oath to stay out of politics.

By the late 17th century, French missionaries of the Foreign Missions Society and Spanish missionaries of the Dominican Order were gradually taking the role of evangelisation in Vietnam. Other missionaries active in pre-modern Vietnam were Franciscans (in Cochinchina), Italian Dominicans & Discalced Augustinians (in Eastern Tonkin), and those sent by the Propaganda Fide– founded in 1622 by Pope Gregory XV and charged with fostering the spread of Catholicism and with the regulation of Catholic ecclesiastical affairs in non-Catholic countries.

As French power grew in the region in the 19th century, the Catholic church followed, with martyrs plenty, and religious strife in Vietnam became embroiled in colonial age politics and warfare for the next century.

An excellent article – perhaps we can look forward to a collection?

The Nestorian Christian missionaries today known as the Holy Apostolic Assyrian Church of the East spread the new faith of Jesus Christ to all nations spreading faith without any contempt up until the Europeans took over and diluted the faith of Jesus enhancing the religion their political superiority thus tweaking the work of the early Christian Assyrian Nestorian missionaries.

Indeed. It’s on record that regional representatives from the Mekong delta region attended a Nestorian Church conference in 450 AD. They were required to represent at least 70,000 Christians in order to attend. So, over a millennium before the Europeans “introduced” Christianity to the region, there were tens of thousands of Christians active in the region. European historians tend to minimize the extent of this peaceful branch of Christianity – even though it was the largest community of Christian believers for centuries – perhaps because it highlights their culture’s misuse and abuse of religion as a tool of colonization and domination. Much like European colonizers in North America who – in the name of Christ – brutally oppressed and destroyed indigenous Christian communities who had converted. Christianity was just a facade to cover the Colonizers’ racism, greed, and political agenda.