King Norodom (1860-1904) did not owe his kingship to an accident of birth, as his European counterparts might, but to his karma, the universal law which decrees that actions in this life determine rebirth in the next, and the next, and the next. Through aeons of reincarnation he had accumulated immense stores of merit, “bon” in Khmer, making him the preeminent “neak mean bon,” man possessing merit, in the kingdom. The proof of this was self-evident: he had been born to a mother who was herself of superior merit (Queen Pen had, after all, married one king and given birth to another), and it was to his merit that he owed his election to the throne, his victory over wicked rivals, and his friendship with the Emperor of the French who had kindly offered him protection. It followed that his opponents — Sivotha, the younger brother who had rebelled against him, for example — were guilty of attacking not merely a king but the order of the universe.

Norodom’s merit had an architectural expression, for he built his palace between the two monasteries of Wat Unnalom and Wat Botum, two of six royal monasteries founded by King Ponhea Yat in the 15th century. Both had great cosmological significance in their own right, Wat Unnalom for a “lom” (a hair) from the “unna” (the whorl of such hairs between the eyebrows of the Buddha) in a stupa behind the main prayer hall, while Wat Botum, the Monastery of the Lotus, possessed the srah srang, a sacred lake filled with symbolic lotus blooms.

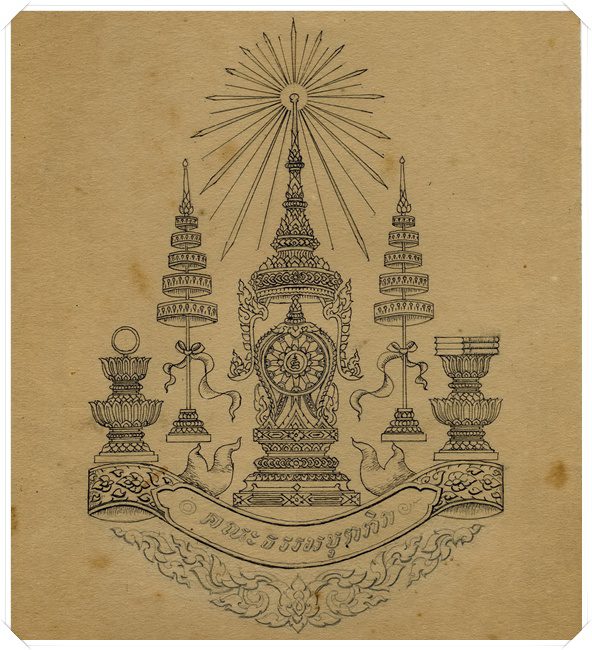

Norodom made Unnalom the seat of the traditional Mahanikay order of the monkhood, and at Wat Botum he established the reform movement called the Thommayut (Thammayuttika Nikai), which originated in Bangkok; his support of the Mahanikay signalled his protection of the Cambodian monkhood as a whole, and of the Thommayut his commitment to its purity.

The differences between Mahanikay and Thommayut bemused and mystified the French, for what was at stake was not the theological questions but matters such as the correct way to wear one’s robe or perform ritual chants (the Mahanikay run phrases together, the Thommayut introduce pauses). It hardly seemed like religion at all. As for Norodom, with his huge harem his personal life seemed quite lacking in any kind of virtue, and in conversation he openly mocked the Buddha. His support of the Thommayut, with its connections to the Siamese court, therefore caused them much concern, and they suspected a secret political agenda in the constant interchange of monks and scholars between Phnom Penh and Bangkok.

In this they understood neither Norodom nor Buddhism. He was in fact extremely religious, but it was a form of religion that put the emphasis not on faith, but on the ritual performance of merit-bringing acts, for it was merit that determined kamma, even for kings.

The sacred hair relic of Wat Unalom, after many adventures, is now housed in a stupa outside the Phnom Penh railway station; the mer sacré outside Wat Botum has been filled in to become a public park with a memorial to Vietnamese-Cambodian friendship, but still has a handsome water feature.

Submitted by P.J. Coggan, Esq.

More reading on the times of King Monivong:

- The Making of Phnom Penh

- French Indochina 1886-1936

- Norodom in Saigon, 1888

- Brau in Cambodia, 1885

- Kennedy & Thomson 1866

- Human Sacrifice 1877

Long lives the King