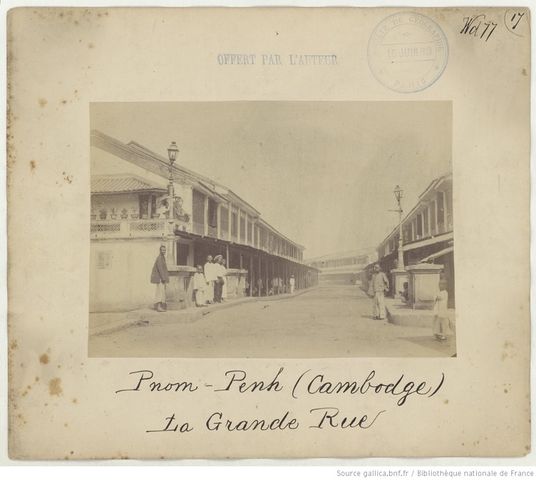

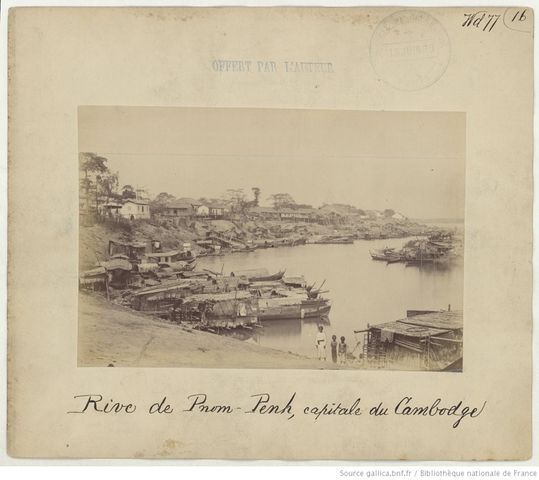

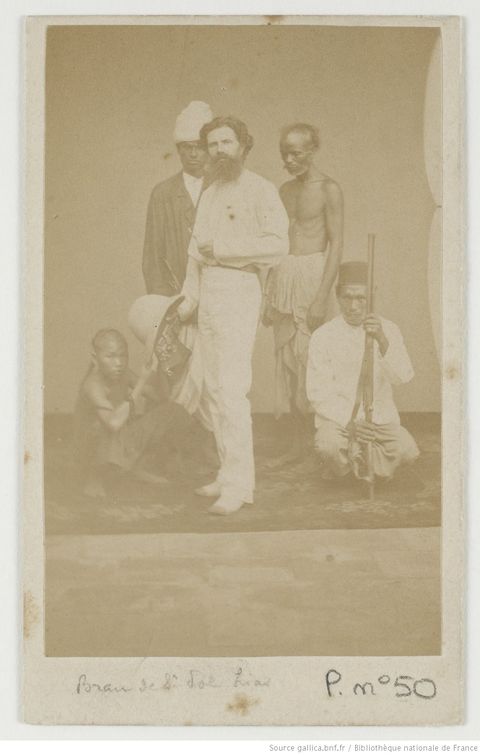

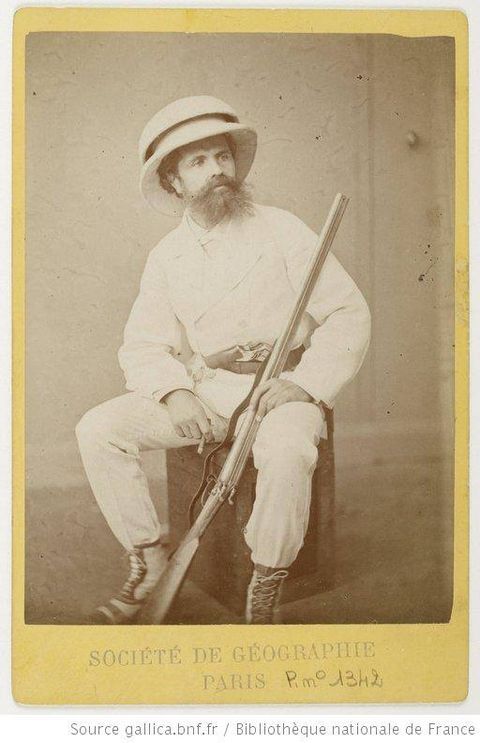

Marie François Xavier Joseph Jean Honoré Brau de Saint-Pol Lias arrived in Phnom Penh from Saigon onboard the steamer Mouhot on Sunday 8 February 1885, en route to Angkor.

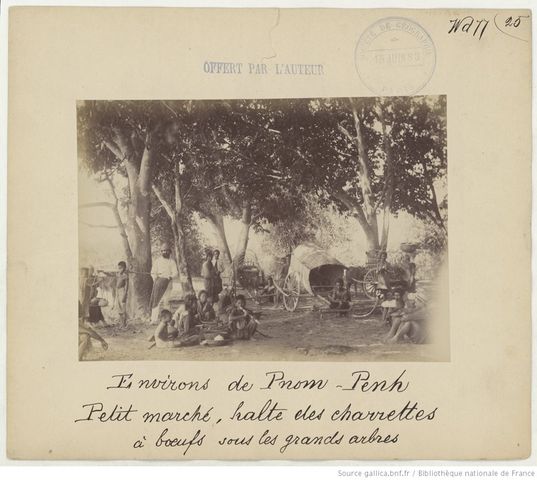

He found the countryside in the midst of an uprising led by Prince Sivotha, a disaffected and intensely anti-French brother of the king, and French civilians had been advised to move into the Residency where they could be guarded by Vietnamese riflemen. After a sudden outbreak of noises in the night; shouts, explosions, barking dogs; Brau grabbed a revolver in each hand and rushed out. It was a false alarm, just the Chinese celebrating New Year with fireworks.

But the Chinese were thought to be in league with the rebels, certainly the Queen Mother was supporting them, and Norodom was behind it all.

A thousand rebels were reported just three hours march from Phnom Penh; French troops and volunteers, and a hundred of Norodom’s men led by a mandarin left to fight them off……

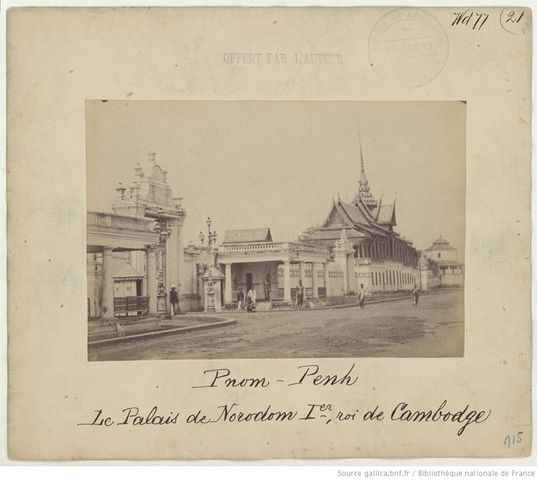

News arrives of further French victories; the emergency passes, and Brau goes to see the palace with Father Joseph Guesdon, a Jesuit missionary who had been trying and failing for several years to convince King Norodom to give up his harem and convert to the true faith. The main gate reminded Brau of Versailles, but its stone was cracked and crumbling. It gave entry to the public courtyard, which Brau finds disappointing:

“You should not, for example, look here, any more than outside, for the least harmony!”

To left and right are the barracks, currently occupied by French soldiers, and the quarters of the princes. Further off are several buildings in European style which Brau rates as attractive, and immediately in front is a walled inner courtyard gold where gold gleams beneath vast curved roofs. This is the throne hall, the centre of the palace.

The doors of the throne hall are closed, but they open for Father Guesdon as if by magic — which is to say that Brau mentions no human hand opening them. Glass tesserae set in the pillars reflect gilded European mirrors and side-tables – Brau expresses no opinion on the décor, but Jean Moura, a contemporary, pronounced it “furnished at great expense in the European style, but quite without taste.”

The polished parquetry floor shimmers under petrol lamps high overhead, and the vault is painted in European style with mythological scenes. Deep within the hall are two thrones, one behind the other, the nearer surmounted by a tower of white parasols, the further nested on a pile of writhing dragons: Above this pile of sculptures and gilding rises a sort of open tabernacle, very high, the dome supported by four small columns touching the vault, where the king sits, Buddha-fashion, with a sanctuary lamp overhead.

A staircase … as on a pulpit gives access to a platform behind the throne, from where a ramp, with many steps, allows one to climb to the tabernacle. Brau climbs, “but mounting the steps of this throne, having seen the powdery and badly-jointed carpentry beneath the opera-set gilding, I feared that it would crumble beneath my feet, and made haste to descend.”

Brau and his guide return to the public courtyard. On the southern side of the throne hall is a vast open shed where “the high mandarins, the ministers, take audiences and give justice.” A little further off is a large pavilion with an iron belvedere “which figured at the Exposition of 1878 and where the king receives European callers and their ladies.” Brau gives it no name, but there can be no doubt that this is the Napoleon Pavilion, today one of the favourite photo-opportunities in the palace.

Beyond the hall of justice and the Napoleon Pavilion lie the gardens and apartments of the women’s courtyard, but a Tagal (Filipino – King Norodom employed Filipinos for his personal guard) at the gate permits no one to pass. As Brau and Father Guesdon are leaving they meet by chance with the eldest son of the king, who presses them join him in beer and cigarettes.

His quarters next to the royal elephant mount, and somewhat apart from those of his brothers. Brau is impressed by the respect with which the prince is treated by the Cambodians: an old servant crawls in on all fours, a courier kneels to deliver a message and does not rise until he is dismissed: and yet there is nothing in the room resembling a throne, and any country schoolmaster in France would be better housed than this heir to the throne of Cambodia.

Later they call on an unnamed brother of the king in a crumbling, smoke-blackened hut apparently outside the palace compound. The floor of split bamboo creaks and bends underfoot and the prince is dressed in a loincloth. Brau marvels at this contempt for show, and his admiration seems genuine.

They also visit the Second King, Norodom’s detested half-brother Sisowath, who has his own palace in the north of the town. “Sisowath come[s] towards us across the courtyard with athletic step, showing us his eagerness. He is extremely gracious and gives us the warmest protestations of his devotion to France.”

He wears his sampot with elegance, he is well shod, his torso is covered, and his comfortable home is totally French. The uprising shows no sign of ending, the trip to Angkor is aborted, and on the 17th of February, 1885, Brau re-boards the Mouhot bound back to Saigon. On the pier he crosses paths with a party of Annamite sharpshooters and their European sergeant, flat caps on their heads and rifles on their shoulders; news has arrived that a hundred and thirty rebels have been killed in a battle: Nous pouvons dormir tranquilles ¬ “we can sleep easy.” Brau wrote these words to welcome the end of the firecracker-torn, dog-tormented Chinese New Year, but he could have been speaking of the peace he believed would return to Cambodia as it fell once more into the arms of France.

Rejoicing was premature. Sivotha managed to reduce French control in Cambodia to the capital and a few military outposts, and on 6 May 1885 a body of insurgents, their number given variously as 500 or 5,000, managed to enter Phnom Penh before being driven off. Things improved only when the French agreed to moderate the demands which had sparked the uprising, and in return Norodom called on his people to put down their arms.

Sisowath took to the field against those who refused to obey, but allowed Sivotha to escape; the irreconcilable prince died in the jungles on the last day of December 1891, abandoned by all. The French were never able to prove Norodom’s complicity, but a tradition current in the royal family up to the 1960s held that he had been in close contact with Sivotha, and the crown prince acted as go-between.

More photos taken by Brau on his Asian adventures can be seen HERE

Brau’s book Phnom Penh HEUREUX QUI COM (French)

Submitted by Philip Coggan (author, historian and all-round good egg)

Further reading:

One thought on “Early Travels: Monsieur Brau At The Royal Palace, 1885”