Phnom Penh, or Krong Chaktomuk Serimongkul- City of the Four Faces (full title, according to Wikipedia: Krong Chaktomuk Mongkol Sakal Kampuchea Thipadei Serey Thereak Borvor Inthabot Borei Roth Reach Seima Maha Nokor- “The place of four rivers that gives the happiness and success of Khmer Kingdom, the highest leader as well as impregnable city of the God Indra of the great kingdom”).

The royal capital for 73 years, from 1432 to 1505, the city was later abandoned as a succession of civil wars broke out.

Even by Asian standards it is a young city, rising from the flood plans little more than 150 years ago. Today it is one of the region’s fastest growing cities- with every generation seeing such rapid development (and destruction) that it would be almost unrecognizable to the last.

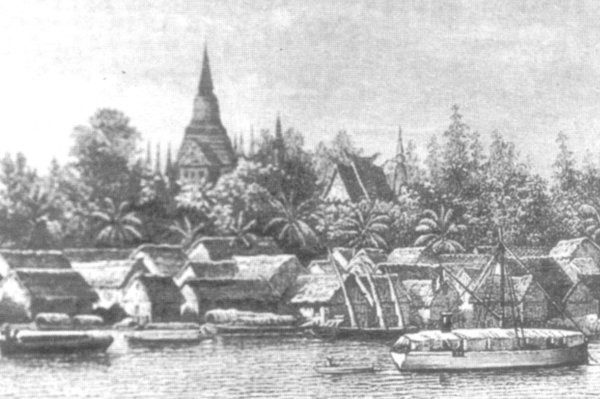

It was Norodom I (reigned 1860-1904) who, in 1865, moved the royal court (along with some 10,000 subjects) to the area where the rivers of the Tonle Sap, Bassac and Mekong converge and began work on the Royal Palace soon after.

The location was a swampy, waterlogged place, with the rivers- useful for trade and access- prone to seasonal flooding and the dry land formed from years of Mekong silt.

Historian Penny Edwards described 19th century Phnom Penh thus: “the city was best known for its vast tracts of mosquito-infested swampland, the stench of stagnant water and human waste, and frequent outbreaks of cholera. In the wet season, boat travel was necessary between different sections of Phnom Penh.”

It was in the 1870’s, with the French protectorate firmly established in Cambodia, that the colonial power, utilizing the latest technology and civil engineering techniques began transforming the “mosquito-infested swampland” into a modern city, which, within half a century would be known as “The Pearl of Asia”.

Henri Lamagat’s work “Memories of an old Indochinese journalist”, published in 1942, described the city under constant construction:

“[in 1906], the Cambodian protectorate, although dating back almost 40 years, was still in the ABCD of its organization. Pnom Penh represented a poor little village – lakeside village during the 6 months of the high season. waters – in which there were only about fifteen streets, European city and Cambodian city combined.

But how original and cheerful was already this hamlet, former capital of the richest and the most glorious of the kingdoms of South Asia!

About 400 Europeans then lived in Pnom Penh, in an islet, of a few hundred square meters, located all around the Pnom and where stood, in addition to the buildings housing public services, trading houses, and private homes. The city’s population, which numbered 12 to 15,000, was almost exclusively made up of Cambodians – then the most numerous – of Annamites and Chinese.

Farmers, breeders, fishermen, tobacco merchants and unrepentant smugglers, they lived on the banks of the rivers, from where their canoes, whose speed defied that of the canoes of the customs, transported successfully, to the nose and to the beards of tax officials, prodigious quantities of tobacco, without paying road tax.

It was only later, after the war of 14-18 that the use of suction dredgers allowed to drain and fill in the immense swamp that then represented PP. Even after the water receded, there were still many deep ponds that completely covered the new quarter on which the new market has just been built. “

Much less frequented by Saigonnais than at present, the capital of the neighboring protectorate, accessible only by river, then had, in all and for everything, only one hotel – Le Grand Hôtel, which has long since become, the Manolis hotel. This establishment, which belonged for ages to the Dumarest house, had been founded by it in the last decade of the 19th century. Its Owner entrusted the operation to tradesmen to whom it rented both the building, the furniture, and all the hotel equipment – silverware, linen and crockery included – necessary to ensure customer service. Despite this, despite the absence of any competition, especially in the early days, the two operators of the Grand Hotel, Burgundians of origin [.. ] had to request the termination of their contract. Both left there, in a few years, everything to them. “

Traditional law had stated that all land was the property the king, whose permission was needed for any construction. Therefore, apart from palaces, monasteries and other religious sites, most pre-French era dwellings and commerce were either lined up against the riverbanks in stilted buildings of wood, bamboo and thatch, or floating houses on the waters.

Earthworks, known as prek were used to control flooding and form reservoirs for dry season water supply. The word is still used in place names, especially to the north of the modern city center.

The French vision of a new, grand city saw the need to shift construction inland. At first the swampy marshland running alongside the Tonle Sap was reclaimed with sand and stone. A grid pattern was laid out, with streets either running parallel or perpendicular to the western banks of the rivers.

A system of drainage canals were dug during the 1890’s- the largest being the Grand Canal which ran was from Tonle Sap, and then ran through Quay Verneville (present-day St. 106), and then vertically through Monsignor Miche Boulevard (present-day Monivong Boulevard), and back east to Tonle Sap via Charles Thomson Boulevard (present-day St. 47).

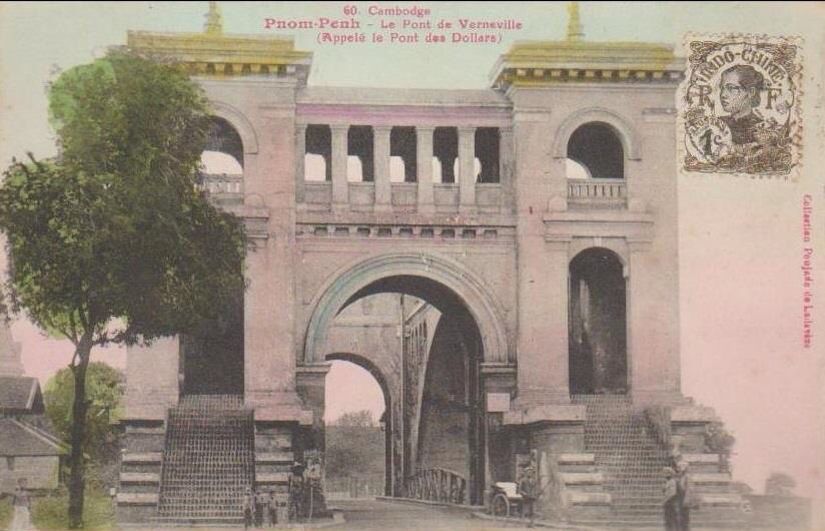

One of the more stunning constructions since lost to development was the Pont de Verneville which crossed the Grand Canal as it reached the Tonle Sap river, somewhere around where the Japanese Friendship bridge. The bridge was named after Monsieur Albert-Louis Huyn de Verneville, two time Résident-supérieur in Cambodia (July 1889-January 1894 and August 1894-May 1897). The bridge was also known as the Pont des Dollars.

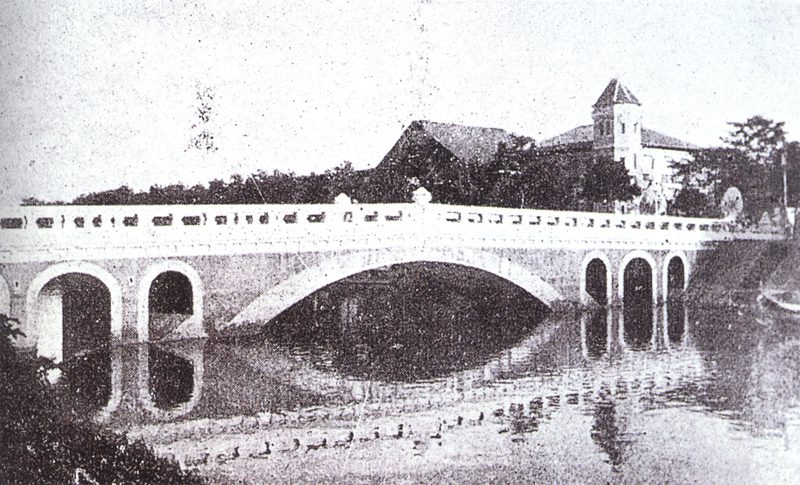

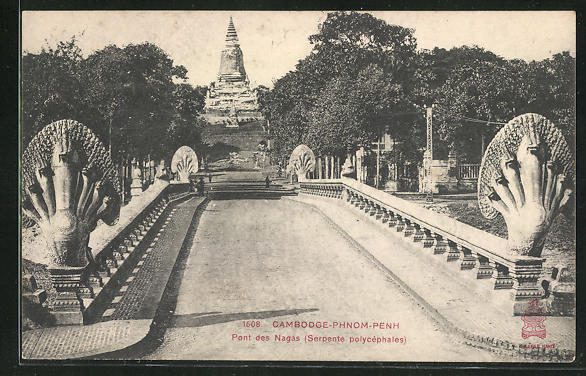

Part of the old canal, later filled in during the 1920’s, can be seen as the thin ‘Freedom Park’ which runs between Streets 106 and 108. Another once famous bridge- Pont des Nagas- was also demolished, and later rebuilt in its original location just south of Wat Phnom at the top of Norodom Boulevard. The bridge, credited by a French source to Daniel Fabre and completed in 1892, linked the Chinese and European quarters and was also known as Treasury Bridge due to the location next to another Fabre building- Trésor du Cambodge -the National Treasury (also built in 1892). The Bridge Tower Building was demolished around 2012.

Sources are unclear on when both Pont de Verneville and Pont des Nagas were demolished, but agree that after the canal was filled, they became obsolete and were most likely taken down in the 1930’s.

The area inside the canal became known as the Quartier Européen– European quarter, with separate districts: Quartier Cambodgienne, Quartier Annamite, and Quartier Chinoise.

The first European to make his mark on the capital was French architect Daniel Fabre (1850-1904), whose most famous work- the Central Post Office building, completed in 1895- still stands in the old Quartier Européen at the top of Street 13. He also was involved in the renovation of Wat Phnom, which by 1893 had the city zoo and surrounding landscape gardens.

Next to the Post Office was the Old Police station, “Le Commissariat”, built in 1892, and currently a crumbling ruin, no doubt awaiting demolition.

The turn of the century, and expanding city- CEEL, a French company built its first water plant at Chroy Changva in 1895, waterways were dredged and a port built- saw the population grow and trade and commerce began to flourish. in 1897, in little over 30 years, the population of Phnom Penh was around 50,000, out of a national population or perhaps 1,000,000. By 1950, it was over 330,000.

Evidence of such new found wealth can be seen in existing building such as the Villa Bodega (also know as the FCC mansion), built for a wealthy Cambodian trader in around 1917. Close by, and of a similar age but in much better shape, is another former private residence now used as the UNESCO office.

Sand dredging technology improved after World War I, and more of the cities lakes and marshes were filled in, and the city expanded to the west.

In the 1920’s Ernest Hébrard- made famous for redesigning the Greek city of Thessaloniki after the great fire of 1917- became involved with extending Phnom Penh. In 1925, the architect and town-planner, who was already working on projects in Hanoi and Saigon, drew up modernization plans, under the responsibility of Indochina Architecture and Town Planning Service (Service de l ‘architecture et de l’urbanisme de l’Indochine), of which he headed.

His best-known landmark which still stands is Le Royal, now run as Raffles Hotel Le Royal to the west of Wat Phnom, which opened in 1929. Other buildings of this period include Phnom Penh City Hall, circa 1925, which was originally a catholic seminary.

To the southwest of Wat Phnom, the Phnom Penh Railway Station was completed in 1932- after much battling with the marshy ground and Cambodian climate. The station had a grand esplanade along what would have been the site of the filled in Grand Canal. Part of this still exists as Freedom Park, the Vattanac and Canadia tower sites have now cut off the view.

A swampy district in the Quartier Annamite/Chinois burned down in 1920. A wealthy Chinese businessman named Tea Maj Yaw soon proposed redeveloping the area with a covered marketplace as centerpiece, but his plans were rejected by the colonial administration.

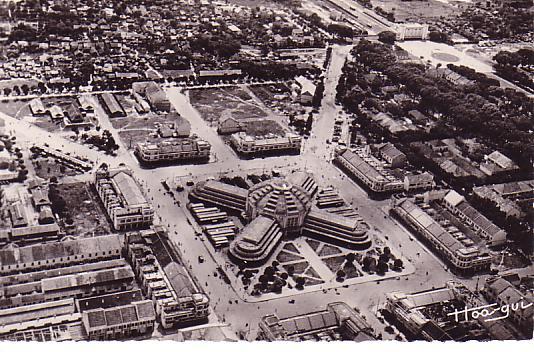

Later, as the area known as Beng Decho was drained, city architect Jean Desbois drew up plans for an art deco masterpiece. Work began in August 1935, supervised by Louis Chauchon and Wladimir Kandaouroff, and was completed in 22 months.

Psar Thmey ‘New Market’ was built- like the railway station- with reinforced concrete, an innovative new material at the time. Inaugurated by King Sisowath Monivong in September 1937, it was said at the time to be the largest market in Asia, and the famous central dome ‘was as large as the Basilica in Rome’.

World War II saw Japanese troops stationed in Cambodia, and following the surrender in 1945, Cambodia’s young king Norodom Sihanouk began a push for full independence.

It was the end of the ‘belle epoch’, and the beginning of the brief Cambodian ‘Golden Age’ of the 1950’s and 60’s. Sihanouk, who saw himself as a ‘traditional modernizer’ and patron of the arts, enacted a nationwide building program for his new kingdom, which had been dominated by foreign powers since the fall of the Angkorian empire.

The principle architect behind this ‘New Khmer’ style was the first Cambodian graduate of the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts in Paris- a man who in his 30’s and early 40’s completed almost 100 projects- Vann Molyvann.

More photos of other buildings can be found HERE

One thought on “The Making Of Phnom Penh: 1865-1940”