Around the Cambodian-Thai border areas between November 1979 and April 1989, there were over 50 direct attacks and battles on land, air and sea between Vietnamese and PRK troops, Cambodian ‘rebel’ groups fighting for the exiled regime and Royal Thai armed forces. By the mid 1980’s Vietnamese army forces under General Lê Đức Anh had reduced from around 200,000 to 140,000 ‘volunteers’ inside Cambodia- which was proving costly for both the Vietnamese economy and international status.

Yet the armed groups operating across the border posed an ever-present threat to the security of the regime in Phnom Penh, and the possible return of the Khmer Rouge to power was in no way acceptable to Hanoi.

Conditions and morale among the PAVN troops were also deteriorating- suffering more from malaria and other tropical diseases than battle injuries. A mid-1980’s Hanoi radio broadcast described infantrymen in western Cambodia as “dressed in rags, puritanically fed, mostly disease-ridden….”

READ: Vietnam’s Forgotten Cambodian War

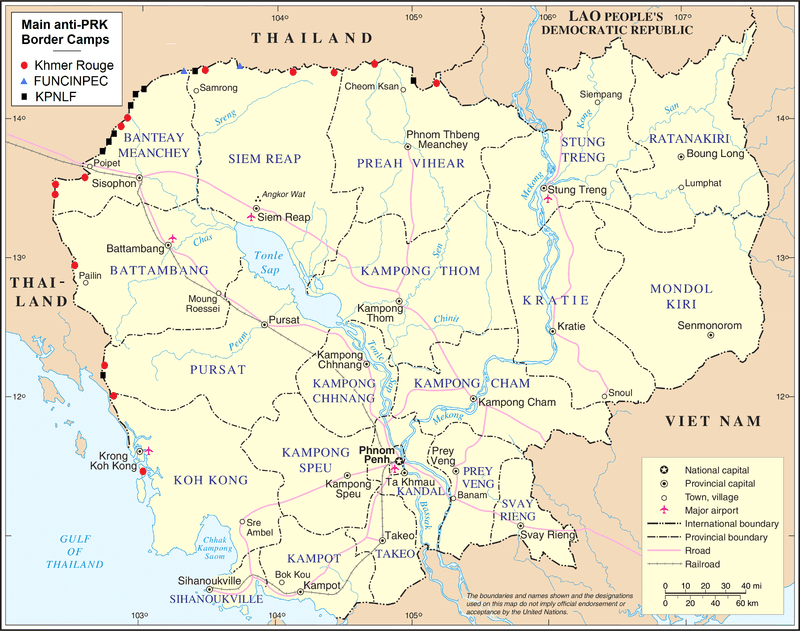

It was decided by General Lê Đức Anh that a 700 km guarded and heavily mined strip along the length of the Thai border, known as the K5 or bamboo curtain, would prevent rebel groups from infiltrating and cut off logistics to camps operating in the mountains and jungles.

With the border secure it was hoped that further Vietnamese withdrawals could be made, and a Khmer manned defense force could take more control with security issues.

Politically, the relationship between the Soviet Union, China and the west was also beginning to thaw as reformer Mikhail Gorbachev rose through the Politburo, officially becoming Party Secretary in March 1985 after essentially controlling behind the scenes of his two terminally ill predecessors.

Before the K5 plan could be put into operation, it was vital to smash the rebel groups based along the border and in Thai refugee camps. Until 1984 a familiar pattern had emerged, with conventional forces of the PAVN taking control of rural areas during the dry season, and being pushed back by irregular fighters during the monsoons when supplies and reinforcements were hampered by the weather.

Therefore the 1984-85 Dry Season Offensive was vital in order to deal a crippling blow to the factions of the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea- an alliance between nationalist, royalist and communist groups formed on 22 June 1982 in Kuala Lumpur, and prop up the PRK’s position in any upcoming peace negotiations.

The chronology of the events of 1984-85 from Wikipedia:

1984

- 25 March-early April: Hanoi launched a 12-day cross-border operation into Thai territory in pursuit Khmer Rouge rebels, using Soviet-made T-54 tanks, 130-mm artillery, and some 400–600 troops. As a result, Thai artillery and air power had to be called into action, resulting in dozens of casualties on both sides and the downing of another Thai military aeroplane. Vietnam’s cross-border raid, along with Thai military and civilian casualties, was reviewed as seriously undermining Thailand’s security. Minor clashes occurred in the area of the Khmer Rouge camp, the Chong Phra Palai Pass linking Cambodia and Thailand.

- 15 April: Six hundred Vietnamese troops of the 5th Division and the 8th Border Defense Regiment first shelled, then entered Ampil Camp, a guerrilla base on the border, killing 85 and wounding about 60 Cambodian civilians. The dawn attack was supported by tanks and artillery. About 50 artillery shells landed on Thai territory near the base of KPNLF guerrillas. In a broadcast monitored in Bangkok, guerrillas loyal to Prince Sihanouk said Vietnam had eight battalions within striking distance of their stronghold at Tatum, a settlement just inside Cambodia’s northern border. Thai troops had been put on full alert to prevent a spillover of the fighting.

- Late May-early June: the Vietnamese Navy repeatedly attacked Thai fishing trawlers off the Vietnamese coast, resulting in the deaths of three Thai fishermen.

- 10 August: Vietnamese infantry, APCs and artillery stationed north of Ampil Camp shelled(?)Nong Chan and Ampil, forcing 10,000 KPNLF troops and civilian refugees to flee into Thailand. Since the 15 April battle for Ampil, the KPNLF had regained control of the camp.

- 28 October: Thai Border Patrol Police capture 5 unarmed Vietnamese infantry regulars who had entered Thailand near Ban Wang Mon southeast of Aranyaprathet, reportedly looking for food.

- 6 November: Vietnamese troops attacked a lightly manned Thai Border Patrol outpost near Surin on the border. Two Thai soldiers were killed, 25 wounded and 5 missing in fighting for control of Hill 424 at Traveng, 180 miles northeast of Bangkok. About 100 soldiers from the PAVN 73rd Regiment pushed about a mile into Thai territory but were later forced back into Cambodia by Thai forces. A Thai military source said the Vietnamese crossed the border in pursuit of Khmer Rouge guerrillas.

- 18–26 November: Nong Chan Refugee Camp was attacked by over 2,000 soldiers of the PAVN 9th Division and fell after a week of fighting, during which 3 Vietnamese captains and 66 Cambodian soldiers of the KPRAF were killed. 30,000 civilians were moved to evacuation Site 3 (Ang Sila) then to Site 6 (Prey Chan).

- 8 December: Nam Yuen, a small camp in eastern Thailand near the border with Laos, was shelled and evacuated.

- 11 December: Sok San was shelled and evacuated.

- 25 December: Nong Samet Refugee Camp was attacked at dawn. The entire Vietnamese 9th Infantry Division (over 4000 men) plus 18 artillery pieces and 27 T-54 tanks and armoured personnel carriers participated in this assault. The Vietnamese deployed both 105mm and 130mm howitzers, Soviet-built M-46 field guns with a range of up to 27 kilometres. KPNLAF guerrillas claimed that 14 Vietnamese tanks and APCs were destroyed during the fighting. An estimated 55 resistance fighters and 63 civilians died in the assaultand 60,000 civilians were evacuated to Red Hill. Approximately 200 war wounded were evacuated to Khao-I-Dang. Numerous KPNLAF soldiers and officers, including General Dien Del, reported that during fighting at Nong Samet on 27 December the Vietnamese used a green-coloured”nonlethal but powerful battlefield gaswhich stunned its victims and caused nausea and frothing at the mouth. Over 3,500 KPNLAF troops held portions of the camp for about a week after this, but in the end it was abandoned.

- 31 December: Vietnamese troops ambushed two Thai Ranger units in Buriram Province, wounding six and pinning them down with small arms fire for over 24 hours.

1985

- January–February: A powerful Vietnamese offensive overruns virtually all key bases of the Cambodian guerrillas along the frontier, putting the Thais and Vietnamese in direct confrontation along many stretches.

- 5 January: Paet Um attacked and evacuated.

- 7–8 January: Five to six thousand Vietnamese troops, backed by artillery and 15 T-54 tanks and 5 APCs, attacked Ampil (Ban Sangae). Vietnamese troops were supported by 400–500 Cambodian KPRAF troops. The attack was preceded by heavy artillery bombardment, with between 7,000 and 20,000shells falling over a 24-hour period. Nong Chan and Nong Samet were also shelled. Ampil camp fell to the Vietnamese after a few hours of fighting in spite of General Dien Del’s predictions. KPNLAF troops disabled 6 or 7 tanks but reportedly lost 103 men in combat.San Ro civilian population evacuated to Site 1. A Thai A-37 Dragonfly ground attack plane, was shot down over Buriram Province during the fighting, killing one of the two crew members. During the assault on Ampil, Thai troops defending Hill 37 near Ban Sangae sustained 11 killed and 19 injured.

- 23–27 January: Dong Ruk and San Ro camps shelled, 18 civilians were killed. Population of 23,000 fled to Site A.

- 28–30 January: Vietnamese artillery fired about one hundred 130mm shells, mortars and rockets at positions of the Khmer Rouge’s 320th Division near the Khao Din Refugee Camp about 34 miles south of Aranyaprathet. This was followed by an infantry assault on Khao Ta-ngoc.

- 13 February: Nong Pru, O’Shallac and Taprik (South of Aranyaprathet) attacked and evacuated to Site 8.

- 16 February: In a skirmish with non-communist rebel forces near Ta Phraya, four Vietnamese rockets containing toxic gas were fired, causing Thai villagers in the area to complain of dizziness and vomiting. A Thai Army laboratory confirmed that the rockets contained phosgene gas.

- 18 February: 300 Vietnamese troops assaulted Khmer Rouge positions near Khlong Nam Sai, 19 miles southeast of Aranyaprathet. Fighting began with small arms exchanges and escalated into a Vietnamese barrage with heavy artillery and mortars. Thai troops fired warning shots at Vietnamese soldiers as they crossed the border in pursuit of fleeing Khmer Rouge guerrillas. One Thai villager was killed.

- 20 February: Vietnamese and Thai soldiers fought on Hill 347, about half a mile inside Thailand’s northeastern province of Buriram. A Thai officer was killed and two soldiers were wounded in the fighting, which included an artillery duel across the border.

- 5 March: Tatum attacked. Green Hill population evacuated to Site B. Dong Ruk, San Ro, Ban Sangae, and Vietnamese Land Refugees are all moved to Site 2. Some 1,000 Vietnamese troops were regularly intruding into Thai territory in attempts to outflank units of the Cambodian resistance groups.

- 6 March: Thai troops and aircraft forced Vietnamese troops to retreat from one of three hills on Thai territory which the Vietnamese had captured during preceding days. Royal Thai Air Force fighter-bombers flew missions against about 1,000 Vietnamese who crossed the Thai-Cambodian border in two places. Some 60 Vietnamese troops were killed in the Thai counterattack.

- 7 March: Thai army troops supported by artillery and A-37 Dragonfly aircraft recaptured three hills seized by intruding Vietnamese soldiers. Hundreds of Vietnamese were said to have been driven back across the border into Cambodia. However, the Vietnamese counterattacked against Hill 361 on Thai soil behind the besieged Cambodian guerrilla base at Tatum, and the results of the battle were not immediately clear. 14 Thai soldiers and 15 Thai civilians had been killed.

- 4 April: A clash occurred at Laem Nong Ian, after five Vietnamese intruded about 875 yards into Thailand.

- 6 April: Thai Border policemen killed a Vietnamese soldier in Thailand during a 10-minute fight near the border.

- 20 April: At southeastern Thailand’s Trat Province, some 1,200 Vietnamese troops attacked Thai positions situated 3 to 4 km from the Gulf of Thailand. Instead of withdrawing the Vietnamese set up a permanent base on a hill in Thailand, about a half-mile from the border, where they laid mines and built bunkers. Later, escalating Thai attacks had pushed some of the Vietnamese back into Cambodia, but the Vietnamese dispatched a fresh battalion of 600 to 800 men to reinforce the hilltop.

- 10 May: A Thai soldier was killed after stepping on a land mine while on patrol.

- 11 May: Thai jet fighters and heavy artillery pounded Vietnamese troops occupying a hill half a mile inside Thailand, and Thai soldiers poised for an assault on the heavily mined position. The Thais bombed and shelled the Vietnamese before an infantry operation was to be launched in the Banthad Mountain range, 170 miles southeast of Bangkok. The Vietnamese were dug in along the hill and had laid a string of mines to counter any Thai ground assaults. Seven Thai soldiers were killed and at least 16 injured. Radio Hanoi reported a Vietnamese Foreign Ministry statement denying the latest reported incursion into Thailand. Thailand accused Vietnam of at least 40 cross-border forays in search of Cambodian guerrillas since November 1984, but the Vietnamese government had denied the charges.

- 15 May: Vietnamese and Thai soldiers clashed for about eight hours with mortars, antitank cannons and machine guns.

- 17 May: Thai soldiers drove intruding Vietnamese soldiers back into Cambodia in intense fighting along Thailand’s southeastern border. After more than a week of fighting, Thai rangers and marines seized part of a Vietnamese-occupied hill just inside the Thai border the previous days.

- May: An approximate 230,000 Khmer civilians were in temporary evacuations in Thailand after a very successful Vietnamese dry season offensive.

- 26 May: Vietnamese soldiers crossed into the Thai province of Ubon Ratchathani from northern Cambodia, apparently searching for Cambodian guerrillas. A Vietnamese force killed five Thai soldiers and a civilian in a one-hour clash with Thai border patrols in northeast Thailand. The fighting prompted Thai provincial authorities to evacuate about 600 civilians from two border villages to safer areas in the Nam Yuen district.

- 13 June: Thai forces battled 400 Vietnamese troops who crossed into Thailand.

Belligerents:

Kampuchean People’s Revolutionary Armed Forces (KPRAF) was officially written into the constitution in 1981, formed from the Kampuchea United Front for National Salvation (FUNSK)- who had crossed the border with PAVN troops in 1979.

Raising and training an army from a country so utterly obliterated by war and the Khmer Rouge regime a difficult task. Recruitment was made initially through KR defectors and local militia units.

Trained and equipped by Vietnamese and Soviet advisors, very little is known about the actual numbers of KPRAF troops- estimates say around 50,000-70,000 regular troops, and another more irregular militia, but are unreliable.

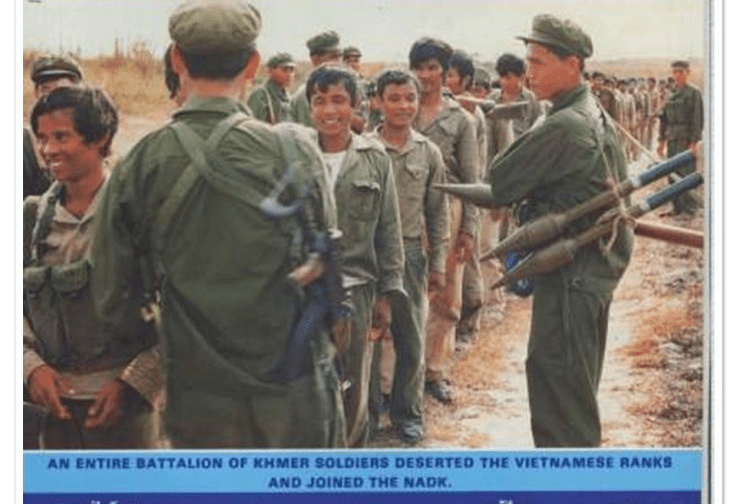

Pay from the state budget was low- around $4-5 a month, plus a rice ration, and desertions were common- some 1,200 defected to the rebel groups between January-September 1986, according to Radio Phnom Penh- but, in the same period around 3,000 resistance fighters also defected to the KPRAF.

Conscription was compulsory, with all Cambodian males between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five having an obligation to serve for five years, increased from three years in 1985, due to shortages. Early reports from refugees in the 1980’s suggested that a ‘press-gang’ system had been implemented, with eligible youths rounded up and forced into service. By the mid-1980’s that appeared to have changed to a more bureaucratic procedure, but dodging military service was reported as being widespread.

Women were also involved in local forces activities, according to PRK official reports, which stated that in 1987 more than 28,000 were enrolled in militia units and that more than 1,200 had participated in the construction of frontier fortifications on the Thai-Cambodian border.

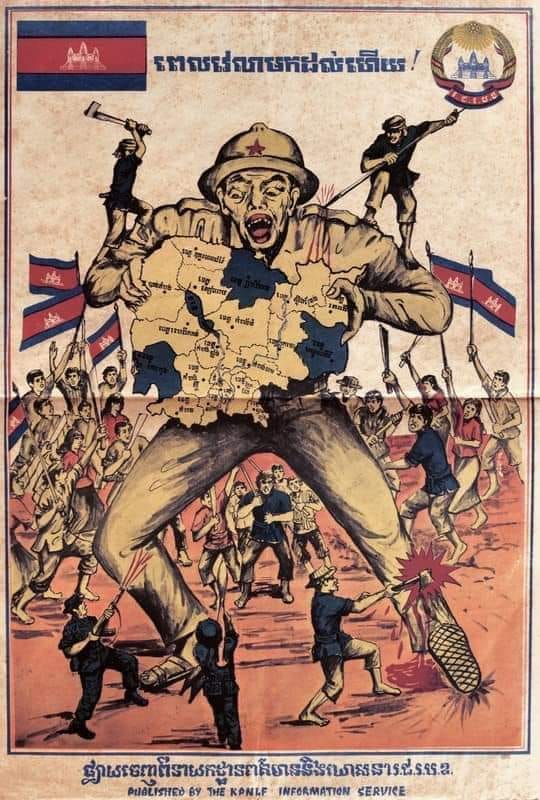

Resistance propaganda played on poor morale, urging Khmer soldiers not to take arms against their ‘brother Khmer’, and cast the Vietnamese as the true enemy. PRK were also involved in psychological campaigns to encourage defections, such as these songs from 1981 and 1983.

Following the Dry Season Offensive, the KPRAF were slowly built up into more of a viable security force, still under the command of Vietnamese ‘advisors’. However, as the Vietnamese army withdrew in 1989, the relative ineffectiveness of the KPRAF, renamed Cambodian People’s Armed Forces (CPAF) the same year, is seen as one factor that brought the Phnom Penh government to the negotiating table, culminating in the signing of the Paris Peace Accords of 1991.

Members of the KPRAF went on to dominate the new Royal Cambodian Armed Forces, which was formed by a merger between the former rebel groups- including FUNCINPEC and some KR units.

National Army of Democratic Kampuchea (NADK) – better known as the Khmer Rouge.

The leaders of the former regime which controlled Cambodia from 1975-79 had mostly fled across the Thai border, or to remote locations along it. With funding and supplies secretly funneled from China into Thailand and onto troops in the field (numbering somewhere between 40-50,000), the NADK were by far the most effective anti-Vietnamese group active inside the country during the 1980’s.

As foreigners were permitted into the PRK, and stories of Khmer Rouge atrocities began to surface on western TV screens and newspapers, the former Democratic Kampuchean went on a rebranding exercise, with the renaming of the Revolutionary Army of Kampuchea to NADK in 1979, and the Communist Party of Kampuchea to the Party of Democratic Kampuchea in 1981.

By the mid 1980’s Pol Pot had relinquished party leadership to Khieu Samphan- although he still remained a large influence- and the movement abandoned its Marxist-Leninist doctrine in favor of self-declared ‘democratic socialism’.

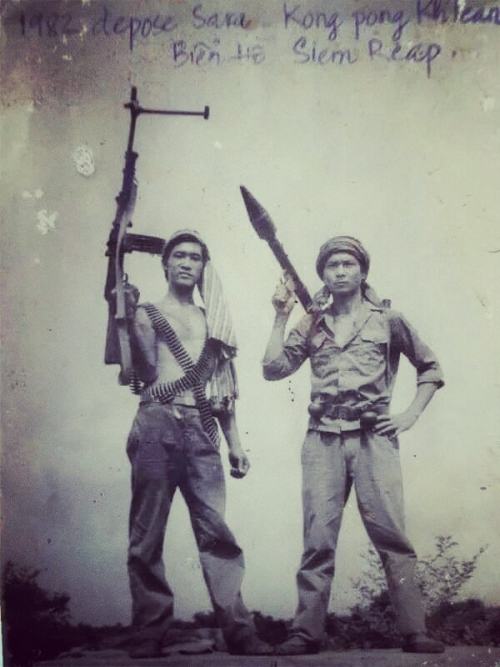

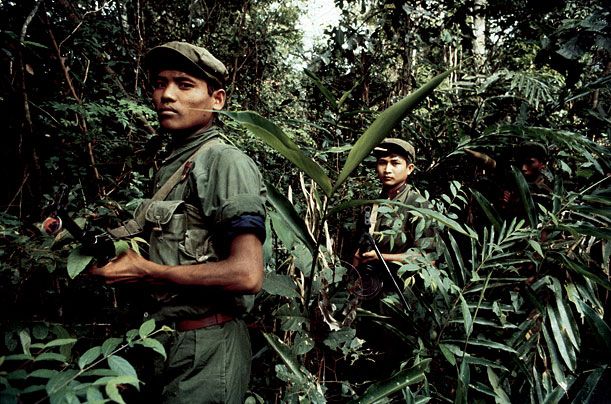

To begin with NADK troops were often involved in a more conventional campaign to recapture and control the border provinces and the strategic Tonle Sap lake. Following the Vietnamese led Dry Season Offensive of 1984-85, the NADK switched to guerilla operations in small groups operating from border camps and remote hideouts within the Cambodian interior.

Supplied with AK-47 assault rifles, RPD light machine guns, RPG launchers, recoilless rifles, and anti-personnel mines the NADK became specialized in harassment and disruption across the country- especially on the roads. Heavily armed convoys were soon needed to transport anything between the urban centers and especially along the route between Phnom Penh and the port of Kampong Som.

The battle for the border had become a battle for the countryside, with whole areas outside the city becoming under de-facto Khmer Rouge administration. Arms and other supplies came mainly through routes across the Dangrek mountains and the Thai port in Trat.

For example, Koh Sla, around 40km north of Kampot town, became the key supply and operational base for Khmer Rouge in Kampot, Takeo and Kampong Speu provinces from the early 1980’s. Setting up an alternative administration in the area, civilians grew crops such as rice which was distributed among rebel groups in the area. Among the commanders who would later rise to prominence were Nuon Paet at Phnom Voar and, in Koh Sla, Sam Bith, who had been Ta Mok’s deputy during the Democratic Kampuchea regime.

From these centers, hit and run raids were carried out, with RPG’s being deployed against armored convoys along the major road links. Booby traps and landmines were then set as they retreated, killing and wounding more PAVN and KPRAF forces as they counterattacked. Fighting was heavier in the north and west of the country, as arms were smuggled across the Dangrek Mountains and from Trat, with the Khmer Rouge still using the Thai border as a semi-autonomous headquarters.

Civilians living in PRK controlled areas were also subject to attacks, kidnap and killings. Despite the new calls for democratic socialism, those living inside the Khmer Rouge zones were still subjected to terrors, not so dissimilar to those experienced under Democratic Kampuchea.

‘Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 1988’, East Asia and Pacific

The emphasis by the Khmer Rouge on the establishment of control over rural Cambodian villages (their “liberation”) exposed increasing number of Cambodian civilians in 1988 to Khmer Rouge tactics which range from bribery through armed intimidation to the summary execution of village leaders and other representatives of the Phnom Penh regime. As in previous years, there are many reports to indicate that disobedience of the authority’s encampments often draws severe punishment, sometimes including execution. This is most often the case in the smaller, less accessible Khmer Rouge camps, but there were instances reported during 1988 in the large, relatively open Khmer Rouge camp of Site 8 as well. In one case, the circumstances strongly suggest that a Khmer Rouge soldier who had resisted returning to the front after visiting his wife in camp was summarily executed.

Khmer Rouge defectors report that civilians and prisoners from Khmer Rouge jails have been killed by mines while performing forced labour, such as transporting supplies for guerilla forces in Cambodia. Prisoners allege that some of these deaths are deliberate, with those accused of serious offenses sent to work in areas where the Khmer Rouge have planted landmines. One former prisoner of the Khmer Rouge said this punishment was called “being sent to cut a tree” — with the tree having mines planted around the base. Such deaths are described by Khmer Rouge authorities to outsiders as accidental. Attempts to flee Khmer Rouge-operated camps for those run by the NCR can also be dangerous, with the risk of being shot by Khmer Rouge guards.

Despite these abuses, the ‘new’ Khmer Rouge were keen to legitimize themselves among the local population, while stoking fears of the encroachment onto Cambodian territory of the old Vietnamese enemy.

Cross border smuggling- food, medicine and luxury goods into Cambodia, valuable timber and gemstones taken into Thailand- was worth millions. As many non-communist warlords carved out fiefdoms in their areas of control, the KR carefully crafted an image of sharing the spoils with those who gave support- building up a patron-client system to boost popularity and recruit new fighters.

Refugees inside Thailand were selected and coerced into so called ‘voluntary repatriations’ into KR controlled zones inside Cambodia. Although promoted as humanitarian, the true objectives were obvious. Singapore’s Foreign Minister even exhorted refugees to “go back and fight.”

Author and academic Kelvin Rowley in Second Life, Second Death: The Khmer Rouge After 1978 wrote

“By 1981, when I visited the Khmer Rouge base at Phnom Malai, the Khmer Rouge were overseeing a functioning society. The area appeared quite peaceful, and under an effective administration, although we were within earshot of fighting with the Vietnamese. The cadres, presumably seeking to counter the image of the Khmer Rouge as “Year Zero” primitivists, made special show of the school and dispensary they had built. But food, housing and other resources were allocated by officials, who had organized the whole population of the area in support of their burgeoning war effort. On the whole, it appeared to be a functioning example of war-communism, not unlike what was reported from the “good” zones in the DK period. But Phnom Malai was not self-sufficient. The uniforms and guns came from China, and the food from markets in Thailand.”

The leadership also remained with the people. While senior figures in the anti-communist resistance groups preferred more comfortable lives to direct operations from Bangkok or Paris, the KR leadership remained in the camps or Cambodian controlled zones- even Brother Number One Pol Pot spend most of his time in refugee camps, especially Bo Rai, just across the border from Battambang province.

As Vietnamese counter operations stepped up in the mid 1980’s, and the conscripted Kampuchean People’s Revolutionary Armed Forces (KPRAF) began to improve in training and morale, the KR found it difficult to hold on to any significant areas and logistics were all but cut off.

Attacks continued after the Dry Season Offensive of 1984-85, such as razing the market in Kampong Speu, and in their first coordinated operation with noncommunist units, attacking a suburb of Battambang.

Isolated pockets of resistance remained inside Cambodia well into the 1990’s- notably Pailin and Anlong Veng, where Pol Pot died as a prisoner of Ta Mok on 15 April 1998.

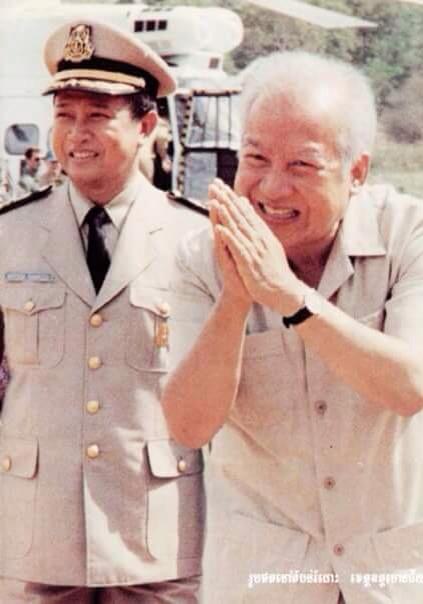

In an US published in May 1987, Norodom Sihanouk reportedly said, “without the Khmer Rouge, we have no credibility on the battlefield… [they are]… the only credible military force.”

Khmer People’s National Liberation Armed Forces (KPNLAF)

The KPNLF was formed from a range of anti-communist and anti-monarchist groups. Many of these groups had formally been little more than armed racketeers, who were more interested in running border smuggling operations and fighting each other than taking up arms against the Vietnamese.

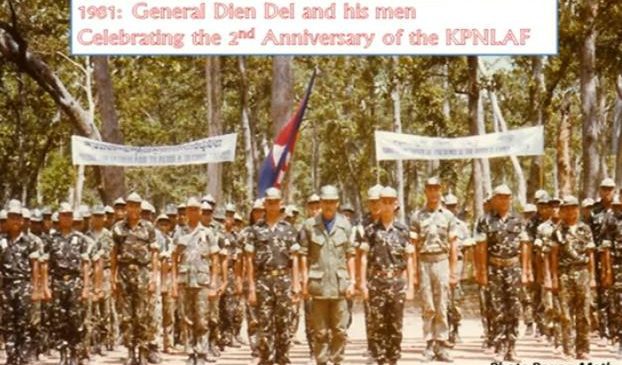

They were united by former Prime Minister Son Sann and former Khmer Republic General Dien Del on 9 October 1979, with around 1600 men. In 1981, former Minister of Defense under Sihanouk and the last Head of State of the Khmer Republic Sak Sutsakhan became the leader. As a respected political leader and military commander, he brought legitimacy and better discipline to the movement, which grew to between 12-15,000 strong by 1984, with other recruits still unarmed.

By mid-1981, with about 7,000 armed members, it was able to protect its refugee camp bases (Nong Chan, Nong Samet and Ampil being the largest) and occasionally cross the border to engage with PAVN and KPRAF troops inside Cambodia.

The Vietnamese Dry Season Offensive of 1984-85 effectively ended the KPNLAF as an effective fighting force.

In April 1984 the Vietnamese, preparing the border long line of defense known as the K5 Plan, began clearing areas of resistance. An assault was launched on Ampil Camp to the northeast of Nong Samet. KPNLAF troops managed to hold off the attack, and after reinforcements arrived from elsewhere, heavy casualties were inflicted on the Vietnamese, who left some 200 of their wounded men to die on the slopes around the camp.

Ampil Camp was destroyed in the fighting, and the KPNLF relocated its headquarters to Nong Chan Camp, which was attacked on November. Two days later the camp was all but destroyed with sporadic fighting continuing until the 30th when the KPNLAF withdrew to Prey Chan (Site 6).

Nong Samet Camp was attacked and destroyed by the Vietnamese on Christmas Day, 1984. KPNLAF troops held portions of the camp for about a week after this, but in the end it was abandoned. 55 resistance fighters and 63 civilians were killed.

It was reported that the entire Vietnamese 9th Division plus part of another totaling over 4,000 men, 18 artillery pieces and 27 T-54 tanks and armored personnel carriers participated in the assault.

Several KPNLAF soldiers and officers claimed that on December 27 the Vietnamese used a green-colored “nonlethal but powerful battlefield gas” which incapacitated and caused nausea and frothing at the mouth.

Following these attacks KPNLAF troops were moved away from civilian camps under pressure from international aid agencies and Thai authorities. Relocation inside Thailand made border crossings difficult, and led to a split between the political movement of Son Sann’s KPNLF and the military commanders, which weren’t resolved until late 1986.

Allegations made by journalist John Pilger caused great debate in the British parliament after Cambodia – The Betrayal, a documentary on clandestine UK government training for the KPNLAF was broadcast in 1990.

It was reported that in 1983 the elite Special Air Service (SAS) secretly provided training to a 250-man KPNLAF commando battalion. Six-man units were taught how to attack infrastructure using small group tactics, booby-traps, landmines and improvised explosive devices, along with battlefield tactics, weapons, navigation, first aid, radio communications, and unarmed combat.

At least six training courses of six to ten weeks were said to have been conducted at a Thai military facility near the Burmese border, and in Singapore between 1986 and 1989.

Two men- Sir Christopher Geidt (now Baron Geidt and Private Secretary to Queen Elizabeth II from 2007 to 2017) and Anthony de Normann- who were linked to British army intelligence- successfully sued Pilger and Central Television for libel after being implicated in the training of Khmer Rouge fighters.

Pilger said the defense case collapsed after the UK government issued a gagging order, citing national security, and prevented three government ministers and two former heads of the SAS from appearing in court. The film received a British Academy of Film and Television Award nomination in 1991.

In March 2009 former SAS soldier and author Colin Armstrong- known under the pen name Chris Ryan -admitted that “when John Pilger, the foreign correspondent, discovered we were training the Khmer Rouge [we] were sent home and I had to return the £10,000 we’d been given for food and accommodation.”

READ: How Thatcher Gave Pol Pot A Hand

READ: Combat Operations with KPNLAF

KPNLAF actions ended in 1989, and the remaining military units were eventually demobilized by General Dien Del in February 1992.

Armee Nationale Sihanoukiste (ANS)– Better known as FUNCINPEC

The ANS was the armed wing of the National United Front for an Independent, Neutral, Peaceful and Cooperative Cambodia (FUNCINPEC) royalist group.

The ANS was formed on 4 September 1982 by uniting of several armed resistance movements that pledged alliance to Sihanouk such as Movement for the National Liberation of Kampuchea (MOULINAKA) and groups in Kleang Moeung, Oddar Tus and Khmer Angkor, giving the ANS a combined strength of around 7,000 troops.

In Tam, a former Prime Minister of the Khmer Republic and MOULINAKA commander was appointed as the Commander-in-chief of the ANS. The ANS received weapons and equipment from China, as well as medical supplies and combat training for its troops from Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand.

Despite officially being allied with the Khmer Rouge in the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK)- the government in exile headed by Sihanouk since 1982- the two groups often clashed.

Top Khmer Rouge commander Ta Mok, was among those who continued to refuse to cooperate with the non-communists. In an interview with Indian journalist Nayan Chanda in New York in October 1986, Prince Norodom Sihanouk said that Khmer Rouge commanders only allowed his ANS to move freely in three provinces, and even then, there were clashes over matters such as wearing the Sihanouk badge, something that Ta Mok’s men objected to.

“Ta Mok can’t bear to see Sihanouk’s face even on a badge. How do you expect the coalition to work?” the Prince said.

There were also tensions with the other coalition partner, Son Sann’s KPNLF, with claims that KPNLAF had become “pirates, smugglers and bandits” who were reportedly selling off arms.

In March 1985, Sihanouk appointed one of his sons, Norodom Chakrapong as the deputy chief-of-staff of ANS, and the following January, another son, Norodom Ranariddh was made the Commander-in-chief of the ANS, replacing In Tam.

Following the near collapse of the KPNLAF due to casualties from the 1984-85 Dry Season Offensive and the infighting that followed, the ANS became the second largest anti-Vietnamese/PRK force. Although some operations were carried out inside Cambodia alongside the Khmer Rouge, restrictions placed on the group by their allies, and diplomatic maneuverings between Beijing, Moscow, Hanoi and beyond, left for little more than political propaganda being spread.

The ANS ranks continued to swell, no doubt a sign of confidence that FUNCINPEC would take control once the war ended, and by the time the Paris Peace Accords were signed in 1991, had a total of 17,500 troops under its command.

The offensive of 1984-85 was a major turning point in the modern history of Cambodia. The threat from outside the country was severely diminished, and the tide had turned to the favor of the PRK and Vietnamese. However, the conflict was far from over, and a guerrilla war continued, mostly waged by KR forces for years to come. Civilians would continue to bear the brunt, either through military activity, forced labor on border defense projects or accidental victims of landmines, which still kill and maim to this day.

Read the whole series so far:

PART 1: End of Angkor- 1800’s

PART 2: The Carved Kingdom

PART 3: French Indochina

PART 4: World War 2

PART 5: Independence to Civil War

PART 6: 1970, A Very Bad Year

PART 7: Questions, April 1975

PART 8: 1979: The Fall of DK

PART 9: The United Nations question

PART 10: Avoiding Famine in 1980

One thought on “Elephant & Dragon 11: The 1984-85 Dry Season Offensive”