With the Khmer Rogue leadership at the UN and Cold War rivalries competing, the situation for Cambodian civilians at the beginning of the 1980’s was looking bleak.

One of the first Soviet teams to arrive in the country wrote to Victor Samoilenko- then in the Foreign Ministry and later Ambassador to Cambodia (1999-2004) “Cambodia needs everything; from plates to pencils. The medical system, the municipal system, the sewage system, water supply, electricity, everything had been destroyed during Pol Pot”

Other socialist countries, including Poland and Cuba sent aid and advisors, and despite the embargo from Western nations, charitable groups such as Oxfam and World Vision, to American Friends Service Committee, Save the Children Australia and Church World Service also sent donations.

Western aid was limited to ‘humanitarian’ rather than ‘development’, which, according to aid worker Eva Mysliwiec was like “giving people fish but not a fishnet”.

On example of this was in 1980, when UNICEF sent sawmill equipment to rebuild schools. However, the organization could not send a technician to help assemble the machinery, nor a representative to assess the project, she said.

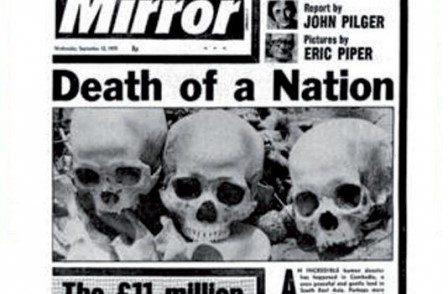

With politicians from across the Cold War divide at loggerheads over Kampuchea, western media was bringing the situation into homes, especially in the UK.

Australian journalist John Pilger, photographer Eric Piper, camera operator Gerry Pinches, sound recordist Steve Phillips and film maker David Monro entered Cambodia, first reporting back in The Daily Mirror, and later in 1979 releasing the documentary Year Zero: The Silent Death of Cambodia

The film, which exposed the brutality of the Khmer Rouge and the hypocrisy of the west, caused a storm on its release.

From John Pilger’s website:

Near the end of the film, he (narrator) refers to a starving boy whose screams can be heard rising and falling in agony. ‘Of course,’ he says directly to the camera, ‘if you’re in Geneva or New York or London, you can’t hear the screams of [this] little boy.’

Year Zero’s broadcast in Britain had a phenomenal public response. Forty sacks of post arrived at the ATV studios in Birmingham, with £1 million in the first few days. ‘This is for Cambodia,’ wrote an anonymous Bristol bus driver, enclosing his week’s wage. An elderly woman sent her pension for two months. A single parent sent her savings of £50.

Screened in 50 countries and seen by 150 million viewers, Year Zero was credited with raising more than $45 million in unsolicited aid for Cambodia, which helped rescue normal life: it restored a clean water supply in Phnom Penh, stocked hospitals and schools, supported orphanages and reopened a desperately needed clothing factory, allowing people to discard the black uniforms the Khmer Rouge had forced them to wear.

Year Zero won many awards, including the Broadcasting Press Guild’s Best Documentary and the International Critics Prize at the Monte Carlo International Television Festival. Pilger himself won the 1980 United Nations Media Peace Prize for ‘having done so much to ease the suffering of the Cambodian people’.

Border Camps

A combination of fear, fighting, famine and propaganda had sent hundreds of thousands to flee to the Thai border.

In what was widely seen as a message from the Thai government, 30-40,000 Cambodian refugees were forced back over the border into a no-man’s land of landmines and booby-traps near Preah Vihear in June 1979.

An international outcry then led to the formation of the notorious border camps- the best known being Khao-I-Dang near Aranyaprathet.

For a brief period following the Preah Vihear expulsions, the Thai government granted an ‘open door’ policy, allowing around 150,000 Cambodian refugees to cross the border into camps. An estimated 500,000 remained on the Cambodian side of the border. The open door was closed again in early 1980.

Prime Minister Kriangsak Chamanan resigned in February 1980, and succeeded by General Prem Tinnasulanon.

The new Thai government, reacting to public opinion, took a harder line on the refugee issue. Most of the camps in the central area of the border were being managed either by UNHCR, UNICEF or ICRC, where as some in the north and south were administered by the Thai military.

In his first foreign-policy speech on March 18 to the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, General Prem reiterated the Thai policy of caring for Cambodian refugees until it is safe for them to return home. But he said Thailand needed more international help and asked for a new conference to deal with the problem.

The general’s comments were compatible with a policy of moving refugees from Thailand’s interior. Cambodian refugees should be placed in “a safe haven along the border” until condition permit a return to their country, he said.

Far from safe havens, these camps were often subject to extortion, smuggling, sexual violence, gangsterism, along with fierce military attacks from all sides.

Internal squabbles between armed Khmer resistance groups active in the camps flared up, such as one case between rivals in the anti-communist National Liberation Movement of Cambodia in Camp 204 (Non Mak Mun) that left at least 46 dead in March 1980.

Thai forces would also fire on the camps- on November 8, 1979 a Thai soldier was accused of raping a Khmer woman and was shot to death. The Thai military commander Colonel Prachak Sawaengchit ordered his troops to shell Camp 511 (Nong Chan). The operation ended with the deaths of around 100 refugees.

The same camps saw incursions by Vietnamese troops. On June 23, 1980, around 200 Vietnamese soldiers crossed the border at 02:00 into the Ban Non Mak Mun area.

The battle that followed lasted 3 days and battle left hundreds of dead, including Thai and Vietnamese soldiers, and scores of refugees who were hit by heavy shelling or caught in the crossfire.

Vietnamese troops then seized Ban Non Mak Mun and shelled other villages. Two Thai air force planes were also shot down.

On June 26 the Vietnamese began withdrawing, taking with them in a somewhat bizarre hostage situation Dr. Pierre Perrin, the ICRC medical coordinator for the border, two American photographers- George Lienemann and Richard Franken- along with a British aid worker, responsible for a controversial aid program that arguably saved Cambodia from a famine that year- Robert Ashe MBE.

The Land Bridge

As diplomats in New York argued over who should be recognized as the legitimate government of Cambodia, fighting intensified around the ‘rice bowl’ regions in the northwest.

Farmers who had survived the Khmer Rogue regime fled towards the Thai border, others who stayed had little in the way of seed, fertilizer or even basic farming tools following the disastrous collectivization of agriculture from 1975-79.

With aid agencies estimating that 2.5 million people were facing starvation at the beginning of 1980, the question of food distribution also became political.

The Heng Samrin led government insisted that all humanitarian aid should be sent directly to Phnom Penh for distribution by the local authorities. While some agencies agreed, there were fears that food and other aid could be withheld from some areas of the population as punishment for supporting rebel groups. There was also the possibility of food either ending up on the black market or used to feed Vietnamese and Cambodian armed forces.

In August 1979, a former naval officer named Kong Sileah formed the Movement for the National Liberation of Kampuchea (MOULINAKA), a pro-Sihanouk resistance force, mostly made up of French-Khmer exiles at Nong Chan (Camp 511). Kong became known for keeping good order inside the camp, although it was the scene for the previously mentioned Thai attack on November 8, 1979.

Following the shelling of the camp in November, Kong met with a 26-year old British humanitarian worker Robert Ashe, who had been involved with Southeast Asian relief efforts for 5 years.

In mid-December, Ashe and Kong Sileah began organizing direct distributions of between 10- 30 kilograms of rice to people who arrived outside the camp from within Cambodia. The word spread and by Christmas 1979 over 6,000 people were visiting daily to collect rice and take back to Cambodian villages.

The rival commander of Site 211- Van Saren, was allegedly running a smuggling operation from Nak Mun and controlled rice sales that had been distributed by aid agencies.

As the ‘land bridge’ became more successful, the price of rice plummeted. On December 30, purportedly with the aid of the Thai army, forces loyal to Van attacked Nong Chan, burning down the hospital built earlier in the year by the ICRC.

Food distribution was only disrupted for a short period following the attack, and by mid-January around 10,000 people a day were again receiving rice. Kong Sileah later left the camp with his soldiers into the jungles of Kampuchea, where he died of malaria on August 16, 1980. The camp at Nong Chan came under the control of Chea Chhut, soon to become a commander of the Khmer People’s National Liberation Front (KPNLF), described by some as a warlord with fewer scruples than his predecessor.

It was not only the privateers and profiteers who had concerns over the land bridge and the direct distribution of food.

In February 1980 CARE (Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere)- an international aid organization- proposed the idea of giving rice seed to Cambodians in order to stimulate a planting drive for the upcoming wet season. Initially, larger organizations such as UNICEF, ICRC and World Food Program were against the idea- worried that it would lead to more refugees wishing to cross the border, and wary of the reaction from Phnom Penh.

Although the official line of the PRK was that all aid be sent to the government, officials did not prevent farmers from traveling to the border to collect seed. After a trial distribution of 220 tons of rice seeds out of Nong Chan on March 21, World Relief and CARE each distributed 2000 tons of rice seed to over 68,000 farmers in early April.

After hearing complaints from the farmers that they did not have tools to work the land, World Relief, Christian Outreach and Oxfam began distributing hoe heads, plow tips, rope, fishnets, and fishhooks, as well as oxcarts in May. During that month an estimated 340,000 people received food and seeds at Nong Chan and returned to their villages to sow.

The land bridge operation came to an end on June 20, 1980. Around 25,520 tons of seed, along with tools and fertilizer had been given out, along with approximately 50,000 ton of food rice to as many as 700,000 Cambodians.

While critics claimed much of the rice had been siphoned and sold to various armed factions, the 1980 rice harvest, although low, was sufficient to prevent the famine predicted in 1979.

The Seizing of Robert Ashe

In the midst of the Vietnamese attack on Nong Chan in late June 1980, Robert Ashe, Dr. Pierre Perrin of the ICRC, and two American photographers- George Lienemann and Richard Franken were taken by armed Vietnamese over the border to Nimit, east of Poipet in Banteay Meanchey.

Told they were considered as prisoners of war, the four were well treated, and after being chastised by PRK officials and Vietnamese minders, they were returned to Thailand a few days later.

Ashe, who was made an MBE in August 1980 for his actions, had what he described as “a memorable experience and one that I would not have missed”

An excerpt from his excellent account of his capture, interrogation and release shows how thrilled he was to see the results of the land bridge inside the PRK.

As we entered the village, we noticed about five large artillery guns positioned in the field to our right and what seemed like a military camp to our left with tents in the fields.

Entering the village, the Khmers began to come out of their houses. It was an amazing experience, as they called back to others still inside the houses: “Robert’s here.” It seemed that nearly everyone had been to Nong Chan at some time or other to collect rice.

We went to one house and sat down to rest for five minutes. The Khmers gathered round, especially the children, and they explained to the Vietnamese leader who I was. He translated it for me, saying that he already knew who I was before he met me because everyone had spoken about me.

I looked round the houses in the village and was surprised to see several things. There were many Vietnamese soldiers living in the village and they had taken over houses interspersed with the Khmers. In and under the Khmer houses were sacks of rice and rice seed. This surprised me because it was clear that it had all come from Nong Chan, and yet firstly, it had not been confiscated by the Vietnamese, and secondly, it had not been confiscated by the village commune. Each individual had been allowed to keep his own stock of rice and seed.

In each garden there were vegetables growing and on the high ground of the village maize was growing. As we continued our walk towards Nimit, a village on the main Poipet – Sisophon highway only one kilometre away, rice paddy fields came into view, and it was lovely to be able to see rice growing in some of them. Later I estimated that 30 to 40 per cent of the paddy fields in sight were already planted with rice.

Results

Famine, for the year had been averted, but, with the Western embargo in place, between 1979 and the end of 1981, UN organizations spent about eight times more on each Cambodian refugee on the Thai border than on Cambodians who had stayed inside the country.

Meanwhile, the disparate factions of rebels along the border began rearming and coordinating better organized operations against the PRK forces and PAVN. The latest war- in a country which had seen little peace for decades was heating up.

Read the whole series so far:

PART 1: End of Angkor- 1800’s

PART 2: The Carved Kingdom

PART 3: French Indochina

PART 4: World War 2

PART 5: Independence to Civil War

PART 6: 1970, A Very Bad Year

PART 7: Questions, April 1975

PART 8: 1979: The Fall of DK

PART 9: The United Nations question

Cover photo: Khao-I-Drang, early 1980’s.

One thought on “Elephant And Dragon 10: Attacks, Aid, And Avoiding Famine In 1980”