On January 11, 1979 the Kampuchean People’s Revolutionary Council (KPRC) proclaimed the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK). The same week, the PRK notified the United Nations Security Council that it was now the sole legitimate government of the Cambodian people.

Hanoi was the first state to recognize the new government, and diplomatic relations with Phnom Penh were swiftly restored. For three days from February 16 to February 19, the PRK and Vietnam held a summit meeting in Phnom Penh and a twenty- five-year Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation was signed. The treaty declared that the “peace and security of the two countries are closely interrelated and that the two Parties are duty-bound to help each other….” Article 2 stated the nations would defend each other against “all schemes and acts of sabotage by the imperialist and international reactionary forces.“

Agreements for cooperation on economic, cultural, educational, public health, and scientific and technological issues were also signed.

The UN Debates January 1979

While 29, mostly Soviet-friendly countries soon recognized the PRK, around 80 took the side of Sihanouk, who, despite objections from the Soviet and Czechoslovakian delegations- who were outvoted 13-2- was allowed to address the UN in New York on January 11, 1979.

Dressed in what Malcolm W. Browne described in the New York Times as wearing “dark gray Chinese‐style clothing” the exiled monarch- who had until two weeks previously been a prisoner of the ousted Khmer Rouge regime- addressed the chamber in both English and French for 40 minutes, to defend it.

Before the session he had told reporters, when questioned on his new links with the Khmer Rouge “It is no longer a question of political differences or human rights, but a question of whether Cambodia shall disappear from the map, to become a province of the Vietnamese imperialists and their Soviet masters.”

He spoke before the United Nations of “flagrant aggression” carried out by the Vietnamese in a “Rommel‐style blitzkrieg” against the Cambodian communists who had been a “brother and comrade‐in‐arms during the war against imperialism.”

Calling on a Security Council resolution, but stopping short of asking for a condemnation of Hanoi, he asked that the PRK remain unrecognized by the UN, and that all aid and assistance from Security Council member states be withheld.

The Prince claimed that forces of the ousted regime were still holding “several towns in the vicinity of the Thai border,” that “our leaders are still inside our country” and that “we will fight to the death.”

He ended with demanding that “Vietnam withdraw from Cambodia totally’”.

The Nazi analogies didn’t end with Sihanouk. After the monarch finished, Chen Chu, the Chinese representative took the floor.

He described the Vietnamese regime as “Hitlerite” blaming Soviet built tanks and planes for massive loss of life, destruction and suffering, and claimed Vietnamese troops had systematically looted Cambodian towns and villages.

Chen then formally introduced the resolution that Prince Sihanouk had proposed. He added that Chinese security was also threatened by the Vietnamese troops massed along China’s southern border. The Chinese would invade Vietnam across the same border less than 5 weeks later and move up to 1.5 million troops up to the northern border with the Soviet Union.

Ha Van Lau, the Vietnamese representative was next to speak. He accused the Security Council of violating the United Nations Charter by even allowing the Prince to be heard, as he represented a government no longer in power.

He said that Vietnam was acting in defense against the border incursions carried out by the ‘Pol Pot-Ieng Sary clique’ and that Vietnam had a ‘sacred right’ to protect her security.

Speaking of atrocities committed by the Democratic Kampuchean regime, which were ‘condemned by the entire world’, he ended his speech by saying that Cambodia had entered a new, better era.

Backing up the Vietnamese position, Cuba’s Raul Roa launched a somewhat personal attack on Prince Sihanouk, whom he labelled an “opera prince” and a “Chinese pawn” under “a senile leader” – a reference to the late Mao.

“When did the Prince speak out against the family separations, the forced moves to the country, the two million people slain, all by the Pol Pot regime? Perhaps when he took strolls with Pol Pot?” Roa asked.

Prince Sihanouk responded in the next day’s debate by calling Fidel Castro, the Cuban leader, an “opera premier….speaking Soviet…never speaking Cuban.” The Cuban delegate, according to Browne “his voice quivering with rage, then called Prince Sihanouk a “pipsqueak.”

The USA, which had not recognized the Democratic Kampuchean regime stated their case through delegate, Andrew Young. He diplomatically noted that, as the United Nations had previously recognized government of Pol Pot as the legal authority in Kampuchea, its representative had the right to speak, even if that government had been overthrown.

Efforts were made by Russian diplomat Oleg Troyanovsky to postpone the talks until the PRK Foreign Minister- a young former soldier named Hun Sen- had chance to arrive in New York. These were overruled and the debate began for a second day.

Ivor Richard, the British delegate, demanded that the Security Council take swift action on the Kampuchean issue, saying ‘it is already clear what the conclusions are that have been reached by the overwhelming majority of United Nations members.’

T.T.B. Koh of Singapore accused Vietnam of lying to the then member states of the Association of South East Asian Nations, citing a ‘good will’ trip made less than three months by Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Van Dong to Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand.

According to Koh, Dong told ASEAN leaders that “Vietnam will respect ‘the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries and that Vietnam will not subvert the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of other countries in Southeast Asia”.

Koh added that “The leaders of Singapore said at the time that we expect Vietnam’s deeds to match its words. We regret to say that after Vietnam’s armed intervention in the internal affairs of Cambodia, my country as well as other countries in Southeast Asia will have serious doubts about the credibility of Vietnam’s words and about its intentions.”

Later in the 1980s, Singapore Foreign Minister Kishore Mahbubani wrote that the Vietnamese Ambassador to the United Nations told him as early as January 1979 that “In two weeks the world will forget about Cambodia“.

Speakers from Zambia, Gabon, Portugal, Malaysia and New Zealand also called for a Vietnamese withdrawal.

Andrew Young reminded Vietnam of its legal obligations under theUnited Nations Charter, prohibiting the intervention of one state in the internal affairs of another, particularly by armed force.

Ha Van Lau of Vietnam reiterated the position that the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge was from a “mass uprising by the entire Cambodian people” in which Vietnam had no part, other than border security.

Lau touched on the subject of the appalling human rights atrocities that had been carried out under Democratic Kampuchea, but stopped short of claiming that any Vietnamese intervention had been done on humanitarian grounds.

The following responses to the debate are quoted from the BBC Vietnamese Service:

The US acknowledges human rights abuses in Cambodia, and also acknowledges that Vietnam has legitimate security concerns when Cambodia attacks the border. But, “border disputes do not allow one nation the right to impose a government on behalf of another with force.”

“No matter what human rights in Cambodia are, it cannot be forgiven for Vietnam, which has human rights, too, it deserves to be condemned when violating the Democratic Republic of Cambodia,” the UK said.

The French ambassador even rejected humanitarian reasons: “The notion that because of an embarrassing government, that can justify foreign intervention and subversion, it’s dangerous.”

The Norwegian ambassador said that Norway “strongly opposed” Pol Pot’s human rights violations, but that human rights violations “could not justify Vietnam’s actions“.

Portugal said Vietnam’s actions “clearly violated the principle of non-intervention” despite the “lousy” human rights record in Cambodia.

New Zealand acknowledged Pol Pot’s Democratic Kampuchea had done many bad things, but “the bad deeds of one country does not justify the territorial aggression of another“.

Australia pointed out that it had no diplomatic relations with Pol Pot but “fully supports the right of the Democratic Kampuchea to be independent, sovereign and territorial“.

Singapore stated: “No country has the right to overthrow the government of Cambodia, no matter how cruel it is to the people. Going against this principle means admitting that the foreign government has the right to intervene and to overthrow. government of another country.”

Following the debate, the fifteen-member UN Security Council, failed to adopt a resolution on Cambodia. Seven nonaligned members on the council submitted a draft resolution- endorsed by Britain, China, France, Norway, Portugal, and the United States- calling for a cease-fire in Cambodia and for the withdrawal of all foreign forces from that country. Objections from the Soviet Union and from Czechoslovakia managed to prevent any official action.

Translated speeches from the debate available HERE

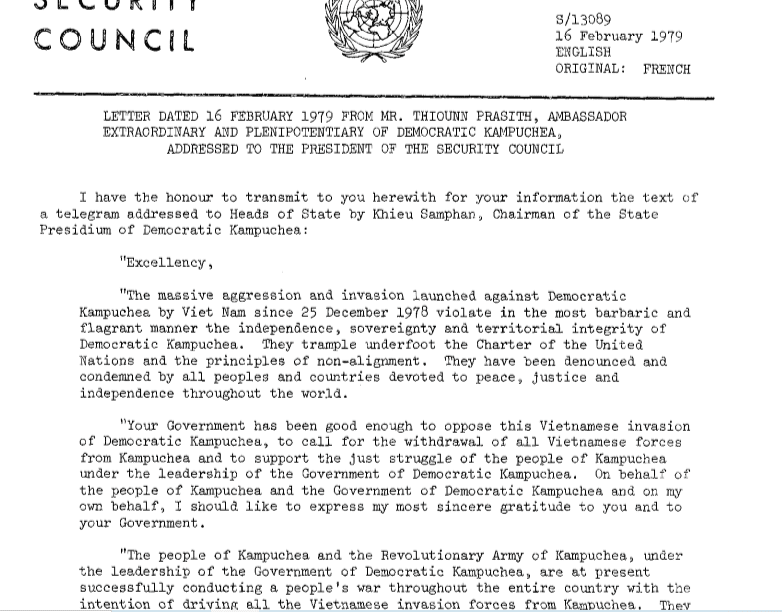

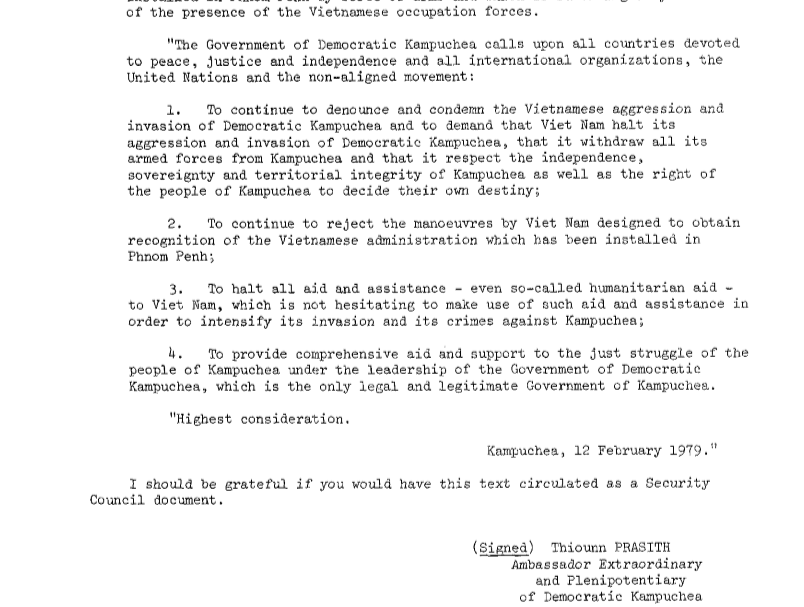

The Cambodian issue looked like it might, as Vietnamese reportedly hoped, be forgotten about. The following month, the Democratic Kampuchea ambassador Thiounn Prasith wrote a letter to the Security Council.

The Sino-Vietnamese War February-March

A few days later, on February 17 1979, Chinese forces invaded Vietnam- seemingly with Washington’s knowledge- if not direct approval.

On January 1, 1979, Chinese Vice-premier Deng Xiaoping visited the United States for the first time, and told American president Jimmy Carter: “The little child is getting naughty, it’s time he get spanked.“

A UN Security Council session was convened on February 23 to discuss the hostilities along the Vietnamese-Chinese border and in Cambodia. China demanded that the UN Security Council censure Vietnam for its invasion of Cambodia, and the Soviet Union asked that the council condemn China for its “aggression” against Vietnam. The United States called for the withdrawal of Chinese forces from Vietnam and of Vietnamese forces from Cambodia.

Tensions rose further as Soviet support began airlifting troops from Cambodia to the frontlines in Northern Vietnam.

Deng warned Moscow that China was prepared for a full-scale war against the Soviet Union and had amassed as many as 1.5 million troops along the Sino-Soviet and Mongolian borders.

When Moscow refrained from reigniting the war along the long, mutually disputed border, Beijing declared that the Soviets had ‘broken their promise to defend Vietnam’. In reality, Deng had already assured both Washington and Moscow that the incursion was to be limited.

The Chinese People’s Liberation Army had not seen active combat since the Korean War and had suffered a series of purges of the officer class during Mao’s Cultural Revolution. The Vietnamese on the other hand were battle hardened and well equipped- the PAVN had seized military hardware left behind by the Americans in 1975.

The Vietnamese had some of the most advanced and well-trained anti-aircraft systems in the world, causing the the Chinese to refrain from using their air force. Vietnamese commando units were able to infiltrate behind the Chinese lines, sabotaging ammunition and logistics equipment.

Weeks of fierce fighting ensued, with heavy losses on both sides. By March 6, China declared that “the road to Hanoi was opened” and began pulling troops back- with large scale looting and destruction of Vietnamese towns and villages as they did so.

On March 16, both sides had claimed victory with areas around Cao Bằng and Lạng Sơn occupied by the Chinese, and the Vietnamese army remained in Cambodia. True casualty rates have never been released, but most estimates believe that a similar number (20-30,000) of combat troops were killed on both sides.

Following the invasion, ASEAN drafted another Security Council resolution expressing “regret’” over “the armed intervention in the internal affairs of Kampuchea, and the armed attack against the Socialist Republic of Vietnam”. The Soviets, once again used veto powers against the resolution.

The Chinese campaign won over several former enemies, with thanks to the new foreign policy and charisma of Deng Xiaoping. ASEAN- especially Thailand and Malaysia who had faced Chinese sponsored communist insurgencies and tension with their own ethnic Chinese populations- now looked favorably on Beijing.

Chinese-American relations were restored, as those with Moscow soured. The ‘détente’ between the US and Soviets, in place since 1969 finally crumbled with the invasion of Afghanistan later in 1979.

Cambodian Credentials

A permanent mission was established- likely with Chinese funding- for the DK near the UN headquarters in New York in March, headed by Thiounn Prasith. The PRK government was still unable to travel much further than Phnom Penh.

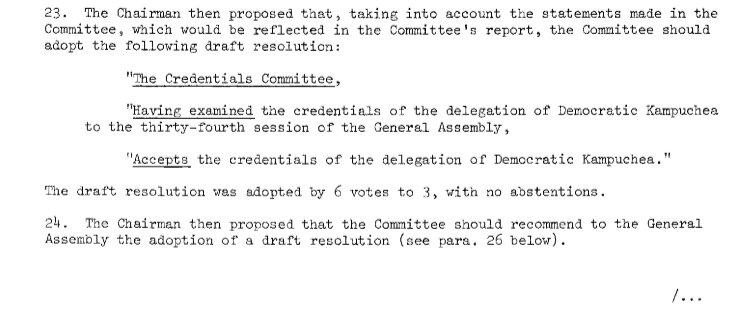

By September, both the exiled Democratic Kampuchea government and the People’s Republic of Kampuchea had both petitioned the General Assembly Credential Committee of the UN with credentials to install the Cambodian UN Ambassador in time for the 34th session in November.

Both sides called for their respective delegations to sit at the session, with Congo proposing the seat be left vacant until the “delicate matter’” had been resolved.

The results are shown here in the original UN letter:

A later vote on the proposals from the Credentials Committee by the General Assembly was less favorable to the DK cause: 71-35-34 in support, but the ousted government of Pol Pot now had the seat at the UN, which they would retain throughout the 1980’s. The Cuban ambassador decried the vote as an action ‘based on letters from a non-existent government which does not control a single inch of territory of Kampuchea’.

The 34th General Assembly, November 1979

The ASEAN sponsored Resolution 34/22 ‘The Situation in Kampuchea’ was heard on November 14 at the 34th Session in New York.

United Nations officials said it was the first time that the organization had censured Vietnam, although did not name the country in the documents. During the debate, however several speakers let it be known that the only foreign power in Cambodia was Vietnam.

The vote, after three days of debate, was cast 91 to 21, with 29 abstentions.

Although little was expected from the outcome, it was hoped that more diplomatic pressure might force Hanoi to come to some terms regarding Cambodia. The five ASEAN states continued to maintain embassies in Hanoi.

Kampuchea Enters The 1980’s

The 1979 dry season offensive began in October 1979, with attempts to crush Khmer Rouge remnants along the Thai border areas. It was clear at the time that the objectives must be made before the start of the 1980 monsoon season in April.

“By April, if they are bogged down in a guerrilla war, which is not unlikely, this will be another pressure on them to rethink their policy,” T. T. B. Koh of Singapore said, prophetically, in an interview during the UN debates.

Behind the diplomatic bluster from the international community, the Khmer Rouge were being rearmed and tacitly allowed safe havens inside Thai territory.

By the end of the year Vietnam had around 200,000 troops inside Cambodia with no plans to leave and let the Khmer Rouge return.

The PRK government under Heng Samrin had inherited a broken country in economic and social ruin. A population had been uprooted, and between 1-2 million died under the DK regime between 1975-79. There was next to no infrastructure remaining and little governance, or those with the ability to lead remaining.

With the world outside the Soviet bloc now against the PRK, and fearful of a Khmer Rouge return, military security took precedence, and famine loomed.

More and more civilians from the northwest-mostly Sino-Khmer who had survived the Pol Pot regime and were fearful of further persecutions- took their chances and fled to the Thai border, creating yet more crisis and instability.

Read the whole series so far:

PART 1: End of Angkor- 1800’s

PART 2: The Carved Kingdom

PART 3: French Indochina

PART 4: World War 2

PART 5: Independence to Civil War

PART 6: 1970, A Very Bad Year

PART 7: Questions, April 1975

PART 8: 1979: The Fall of DK

Sources: UN Library, New York Times (Browne- Jan 12-14 1979, Schumacher Nov 15 1979), Cambodia Confounds the Peacemakers- MacAlister Brown, Joseph J. Zasloff, BBC Vietnamese