After seizing power in April 1975, the newly installed Khmer Rouge regime- known locally as the ‘Angkar’ and internationally as Democratic Kampuchea- was quick to live up to its ambitions of reclaiming land lost over the centuries to Vietnam. With the Vietnam war almost over, Southern Vietnam in mid-April was in chaos- a situation which the Cambodian communists seemed eager to exploit.

Just two days after the fall of Phnom Penh the Vietnamese island of Phu Quoc (known as Koh Tral to Cambodians), 15 km off the coast of Kampot, was shelled by forces under the command of Ta Mok’s son-in-law Khe Muth.

Early in May 1975 a Khmer Rouge raiding party briefly held parts of the island, reportedly raising the plain red flag of revolution on the beach. The Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam (the country would not officially unify for over a year after the fall of Saigon) sent helicopters to strafe the beach. The Cambodians were finally forced off when a contingent of North Vietnamese Army troops arrived to clear them from the island.

On May 10, 1975, Khmer Rouge forces occupied Thổ Chu Island, 120 km south of Phu Quoc and took around five hundred Vietnamese civilians to Cambodia where they were all killed. From May 24 to May 27, 1975, Vietnamese forces attacked and recaptured the island. The Khmer Rouge raided Thổ Chu Island again in 1977, but were repelled.

Cambodian claims to Phu Quoc were dropped in 1976, but border skirmishes continued, culminating in what is remembered in Vietnam as the Ba Chúc massacre.

Vietnamese Retaliation

Khmer Rogue shelling of border villages in September 1977 led to the deaths of around 1,000 civilians in Đồng Tháp province. On 16 December 1977, an estimated 60,000 troops from the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) assembled on the border and launched an attack, which overran the Cambodians and came to within 30 km of Phnom Penh before withdrawing on January 6, 1978.

Despite being delivered a humiliating defeat and being heavily outnumbered, Cambodian attacks across the border continued, including the overrunning of border posts in Ha Tien the same month. Another large Vietnamese force was then assembled all along the border, which infuriated the Khmer Rouge. The Vietnamese air force began targeting bombing raids on KR forces inside Cambodia, further raising tensions.

Instead, Pol Pot’s government boasted that the Vietnamese withdrawal was a major victory for Democratic Kampuchea, comparing it to the “defeat of U.S. imperialism” on 17 April 1975.

“our 6 January victory over the annexationist, Vietnamese aggressor enemy has given all of us greater confidence in the forces of our people and nation, in our Kampuchean Communist Party and our Kampuchean Revolutionary Army, and in our Party’s line of people’s war“.

Soldiers were told that a single man was equal to 30 Vietnamese soldiers. Two million soldiers from a population of eight million were said to be able to defeat Vietnam’s population of some 50 million. The fact that a disastrous agricultural policy, and genocide of hundreds of thousands, had left those still alive starving was conveniently ignored.

The Vietnamese, not long out of decades of war, were among the poorest people in the world. However, the communist takeover of the south had been completed without the killings and upheaval experienced in Cambodia. And, although poor, the country was undergoing reconstruction, with Soviet economic aid alone between $0.7 billion and $1 billion in 1978 (around $4 billion in today’s rates). And, while undoubtably living under a repressive regime, the Vietnamese population were generally in far better physical shape than those in Cambodia, who were being worked to death, suffering from starvation and disease.

Perhaps just as crucially, the sponsors of the Democratic Kampuchea regime, China, were also in a weaker position than ever. The Cultural Revolution, led by Mao, had been a driving inspiration behind Pol Pot’s ‘Year Zero’ ideology in Cambodia. Mao was now dead, but so too were hundreds of thousands of peasants, intellectuals and those in the political and military classes. This loss would show itself in early 1979, when Chinese People’s Liberation Army troops invaded northern Vietnam and were fought to a standstill by Vietnamese militia units..

In early 1978, Vietnamese Deputy Foreign Minister Phan Hien made several trips to Beijing to hold discussions with representatives of the Kampuchean government, with little success. On 18 January 1978, China attempted to mediate between Kampuchea and Vietnam, but when Vice Premier Deng Yingchao travelled to Phnom Penh, she was met with strong resistance by Kampuchean leaders.

Purges of Khmer Rouge cadres across the country, especially those who had previously had training and support from Hanoi saw many fighters and commanders, most notably from the Eastern Zone- labelled ‘a nest of traitors’ by Pol Pot- defect across the border in 1977-78. Among these were Heng Samrin, Chea Sim and current Prime Minister Hun Sen. The purge of the Eastern Zone was carried out by cadres from Ta Mok’s Southwestern Zone. At the same time, Vietnamese government officials began conducting secret meetings with So Phim, the commander of the Eastern Zone, to plan a military uprising backed by Vietnam.

A ceasefire to last for 7 months was requested by Cambodia on April 12, 1978, which was rejected by the Vietnamese. On April 17, 1978, a speech by Pol Pot was broadcast across Cambodia to celebrate the 3rd anniversary of Democratic Kampuchea. It was filled with vitriol against ‘the youn’ (a term used in Cambodia for Vietnamese). Three days later the most brutal assault against civilians in Vietnam since the war ended occurred. Khmer Rouge from the Southwestern Zone crossed the border into An Giang province and unleashed a terrible wave of violence upon the civilian population of the village of Ba Chúc. At least 3,157 civilians were butchered, leaving just a handful of survivors.

Accounts say that many of the attackers lacked guns, and instead stabbed or bludgeoned men, women and children with knives and clubs. 40 died when grenades were thrown into a local temple where they had been sheltering.

After 12 days of bloodshed, Vietnamese forces finally responded, killing several Khmer Rouge as they retreated. Other reports say that the fleeing Khmer Rouge placed random landmines behind them, which may have killed up to 200 more in the weeks and months after the attack.

Ba Chúc massacre memorial

Invasion and Occupation

Enough was enough for the Vietnamese and a plan was hatched to remove Pol Pot and his deputies from power. Another Vietnamese incursion took place in June 1978 in the Eastern Zone, once again KR artillery was moved back and returned to the border and resumed shelling after the PAVN withdrew.

Vietnam signing a treaty with the Soviet Union guaranteeing military aid on 3 November 1978, earlier that year on June 29, Vietnam became the 10th member of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON)- a Soviet led communist trading bloc.

A home grown resistance force to overthrow the Pol Pot regime, The Khmer United Front for National Salvation (FUNSK), was formed in Kratie province on December 2, 1978. Ta Mok’s long-time rival Heng Samrin was elected leader of the movement, which gave an air of legitimacy to the planned invasion and overthrow of Pol Pot by the government in Hanoi. Soon 350,000 Vietnamese troops had been drafted and placed along the border.

As the threat of Vietnamese invasion loomed, Democratic Kampuchea had an estimated 73,000 soldiers in the Eastern Zone bordering Vietnam. Chinese-made military equipment was also rushed into place, which included fighter aircraft, patrol boats, heavy artillery, anti-aircraft guns, trucks and tanks. There were also between 10,000 and 20,000 Chinese advisers, both military and civilian in the country.

On December 21, 1978, two Vietnamese divisions crossed the border and headed for the town of Kratie, supporting divisions moved in to cut off Kampuchean army logistics. The defenders were overwhelmingly crushed.

Four days later, o December 25, 1978, Hanoi launched the offensive with twelve to fourteen divisions and three Khmer regiments with a total invasion force comprising of between 100,000-150,000. Five spearheads were launched simultaneously.

In the face of such an onslaught, heavy fighting was localized. A major engagement was fought around Tani, near Angkor Chey, but with few experienced commanders following the purges, and an underfed army, the Khmer Rouge scattered after heavy artillery and airstrikes pounded their positions. Some retreated to the west to regroup, while others melted into the countryside and mountainous jungles.

On January 6, 1979, the Việt Nam People’s Navy launched a naval landing, with the aim of capturing Kampong Som Port and Ream military base, to prevent the Khmer Rouge being resupplied by the sea. They faced the Khmer Navy Division 164 and Border Guard Regiment 17 who held the southern defensive line.

In five days of fierce fighting on both sea and land, Vietnamese forces succeeded in wiping out Navy Division 164 and Border Guard Regiment 17 and took control of Kampong Som Town and the Ream Military Port, thus securing access to the coastal southeastern part of the country.

In Phnom Penh, PAVN troops, along with members of the FUNSK entered the empty Phnom Penh virtually unopposed. Much of the Democratic Kampuchea/Khmer Rouge leadership fled to the Thai border, where they were permitted to make a camp at Khao Larn.

Thailand’s Cambodian Conundrum (1973-78)

Bangkok, which had for the most part been diplomatic with Pol Pot regime, was suddenly faced with two overwhelming problems.

First, the ancient enemy of Vietnam now had regular troops stationed along the Thai border, less than 300 km from Bangkok. Worse still, this was a communist Vietnamese army. Thailand had long feared communism, and President Eisenhower’s ‘Domino Theory’ of collapse of neighboring nations touted since the late 1940’s suddenly became a revived in the minds of the fragile Thai political classes who had 11 coups or attempted coups since the 1930’s.

The second problem was humanitarian. As many as 750,000 Cambodians had fled to the border, some fleeing the fighting, others used as human shields and forced labor by retreating Khmer Rogue fighters. There were also cases of civilian massacres committed by troops from Ta Mok’s Southwestern Zone as they withdrew through the countryside.

Following the overthrow of pro-American military dictator Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn in 1973, Thai foreign policy towards neighbors in the region softened and American forces were withdrawn. At the same time the communist insurrection in the north was intensifying, and following 1975, Khmer Rouge forces frequently attacked Thai villages and border posts.

Another military coup in Bangkok in 1976, led to General Kriangsak Chomanan (Secretary-General of the National Administrative Reform Council and shortly after Thai Prime Minister) to declare “We want good relations with Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia” and “our policy towards China has not changed.“

The government of General Kriangsak saw the biggest threat to Democratic Kampuchea’s survival came from Vietnam, and that the Khmer Rouge would eventually come to terms with Thailand.

Following more border raids following his ascension to Prime Minister, Kriangsak played down incidents, suggesting confusion, poor communication or even inaccurate maps may have caused the incidents.

Thai Foreign Minister Upadit Pachariyangkun’s made a “goodwill visit” to Phnom Penh in late January 1978, which resulted in an agreement to exchange ambassadors, but border raids into Thai territory continued in February. Even after Thais were killed, “reports” rather than “protests” were lodged because “Cambodian leaders might not know what is happening on the border.”

The Border Warlords

In ways this was probably true. Khlong Yai District is a long sliver of land wedged between the Gulf of Siam and Koh Kong province. Its very existence as an odd Thai outpost owes itself to the 1907 agreement between the French and Siamese, which involved horsetrading of territory ranging from Trat to Siem Reap.

The local Khmer Rouge commander, a Comrade Veun, safely isolated from the ‘all seeing’ Angkar, took up position as a modern day feudal warlord and set about running a smuggling racket, with the help of Thai officials and businessmen across the border.

In order to keep up appearances- and possibility to make sure the business ran smoothly- Veun’s troop would fire the odd shell across the border at the outnumbered detachment of Thai Marines, who knew they could not hold the strip in the face of a serious assault.

The arrangement worked well up until February 1978. With the eastern border clashes heating up, Comrade Veun discovered there were plans to redeploy his unit to Kampot. Reluctant to lose his fiefdom and face certain death fighting the Vietnamese, Veun decided to show how much he was needed in the west by shelling the border, hitting Thai military and border guards, who responded in kind.

Around 3000 of the 4000 inhabitants fled by boat, as the single road to Trat came under attack. Having ‘’accidentally escalated” the situation, the Cambodian side, apparently realizing shooting the neighbors was bad for business, suddenly “de-escalated” according to Thai authorities, and life returned to the status quo in southern Trat province.

Illicit trade had flourished along the mountainous 800 km border for as long as it had been there. Away from the hard-line party centers, local commanders, such as Comrade Veun could obtain luxuries from across the border while millions of their countryman starved. Limited legal trade was also rarely permitted on occasions, and as late as 1978, trade negotiations were still being held between Phnom Penh and Bangkok.

The border attacks were mutually blamed on each other by both sides but unlike the Vietnamese who responded with military force, such incidents were isolated, downplayed and rarely escalated further than a few exchanges of fire.

Thai Border Problems 1975-78

Khmer Rouge paranoia also extended to Thailand, as the border was regarded as a possible entry point for “CIA agents” and “Khmer traitors” – former Lon Nol troops who had fled at the end of the civil war.

An internal communique from February 7th, 1977, apparently justified boarder raids, stating: “The Thai government has maintained, helped, protected and organized these traitors so that they continuously carry out provocative activities against Democratic Kampuchea”.

Former Prime Minister Im Tam, who had managed to escape from his farm in Poipet at the end of the civil war, did attempt to raise a resistance movement, but was deported from Thailand in 1976. His shadow still apparently loomed over the regime, with In Tam becoming synonymous with any resistance on the western frontier.

An internal telegram of April 11th, 1978, reports that “the Thai enemy encouraged the In Tam troops to launch activities to disturb us along the border by organizing their troops into small groups to intrude into our territory in order to launch hit-and-run attacks and to spy on us as well. […] These traitors are based along the Dangrek Mountains and we have plans to find their bases to crush them”

Purges of cadres were carried out in the Western and Northwestern Zones too. Khmer Rouge ‘confessions’ from the Tuol Sleng archives include the former secretary of Democratic Kampuchea’s Western Zone, Chou Chet (alias ‘Sy’) told his interrogators on May 20th, 1978, that he was part of an alleged 1977 coup plot with cooperation of defected KR forces and the Thai army to invade Democratic Kampuchea from Preah Vihear towards Kampong Thom.

Former Northern Zone secretary Koy Thuon’s ‘confession’ includes plans to “to assemble Thai, American, and Vietnamese patronage and support”. Another Thai-supported coup attempt is mentioned by S-21 inmate Prum Ky, a former KR village chief and army leader. He said that a “plan to be implemented in April 1976 will be to capture Koh Kong as our base, from which we will achieve victory over all targets. When we win, we, in cooperation with Thai troops, will break through national road 4 to Phnom Penh”.

Other such ‘confessions’ of former North-Western Zone cadres, purged in 1977, admit to a range of counterrevolutionary cooperation between Thailand and local groups, with accusations made of “allowing others to flee the country, offering Cambodian territory to the Thais, plotting with Cambodian exiles, and trading rice to Thailand”.

Khmer In Thailand

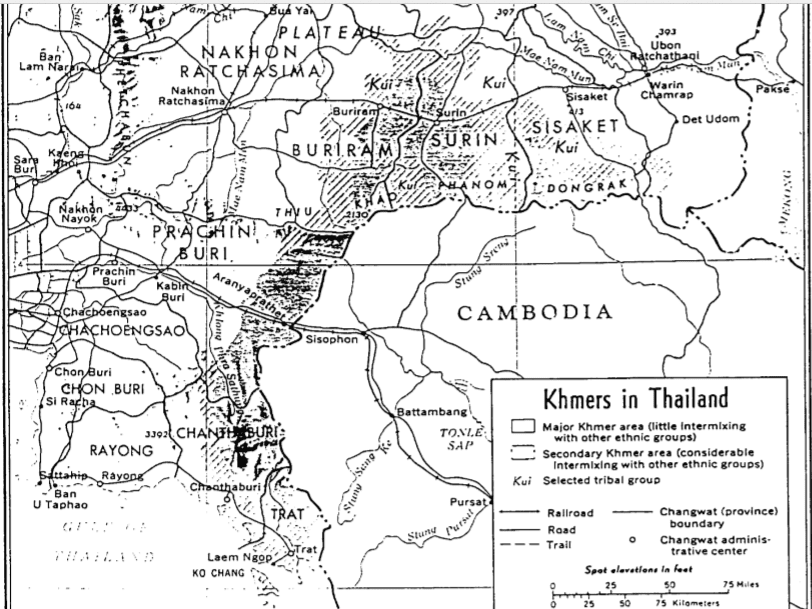

Khmer communities had flourished in Isaan region of north east Thailand and along the border provinces. A CIA intelligence document gathered information from 1960-70 and estimated there were 600-800,000 ethnic Khmers living in Thailand, described as “an impoverished but peaceful minority”. Only a few thousand had been born in Cambodia, and many communities had been there since the time of Angkor.

The report noted the similarities in appearance of both Khmer and Thai peoples, their Buddhist beliefs and agricultural methods- but kept their language- with men and the young often being bi-lingual, women less so. In some rural ‘Khmer’ areas 78% of the population could not communicate in even basic Thai. It was also noted that Thai-Khmer spoke with a different accent and sometimes had difficulty understanding Khmer language radio broadcasts from Phnom Penh.

During the civil war, several thousand Cambodians took refuge in Thailand, but only as a fraction of what would come after the fall of Democratic Kampuchea. Some managed to escape or defect across the Thai border during the Democratic Kampuchea period, as seen in the video above. During the refugee crisis that would begin in late 1978 and last over a decade, these ‘old Khmer’ were treated differently to the new arrivals.

A New Alliance

As the new government consolidated power with the aid of at least 200,000 Vietnamese troops, the new republic quickly found itself isolated from much of the non-communist Warsaw Pact world.

While the new regime was eager to cast itself as liberators, while those who had been defeated in the wars of the 1970’s- Sihanouk, Khmer Republicans, and now the Chinese and Khmer Rouge denounced the ‘puppet regime’- headed mostly by KR defectors- and the Vietnamese as occupiers. In yet another display of Cambodian cynicism, these former bitter enemies put aside old feuds and another lose alliance was formed. All of the Cambodian factions, along with the Thais now had to face up to the reality that their biggest fear- a Vietnamese army inside Cambodia- was now a reality.

China and Thailand, who had long been at odds over the Thai communist insurgency, restored relations. The insurgency in the north was ended, supposedly through a series of amnesties granted. Prime Minister Kriangsak Chomanan denied reports in British media claiming a secret deal ended the insurgency in return for allowing Chinese weapons to be shipped to the Khmer Rouge.

Western nations viewed the invasion/liberation as Soviet aggression. The United States’ relationship with China also thawed, and supported the anti-PRK alliance.

For the people of Cambodia, who had lost as many as 2 million of their countrymen under the Khmer Rouge, along with the hundreds of thousands killed in the civil war, the next decade would also prove to be a difficult time. As many as 700,000 would soon be living in refugee camps over or along the Thai border, and those who remained in the People’s Republic of Kampuchea would face even more years of hardship, famine and yet another long and brutal war.

Sources used include: Henry Kamm- New York Times/AP, CIA archives, East German Diplomatic Archives (translated by Christian Oesterheld), The Economist- ‘Obituary of Kriangsak Chomanan’, VietnamExpress, Wikipedia

Cover image: Thai border guards watch for refugees and Khmer Rouge attacks, Aranyaprathet, 1977 (NBC)

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and not CNE.

PART 1: End of Angkor- 1800’s

PART 2: The Carved Kingdom

PART 3: French Indochina

PART 4: World War 2

PART 5: Independence to Civil War

PART 6: 1970, A Very Bad Year

PART 7: Questions, April 1975