Author’s note: This series skips the civil war period from after 1970-74. I have written several pieces already on this time period.

The Cambodian Civil War ended when Phnom Penh was finally overrun on April 17, 1975. Most contemporary accounts give credit to ‘Khmer Rouge’ forces, but the facts on the ground, as always, were much more complicated.

Several questions remain over the fall of Phnom Penh, and end of the Khmer Republic, which perhaps go against the usual narrative.

Lon Nol

On March 22, 1975, Deputy Premier Pan Sothi was one of about a dozen ministers and generals who signed a statement presented to the President of the Khmer Republic calling on him to stand aside for the good of the country.

On Tuesday April 1, Lon Nol, partly paralyzed from a stroke, walked slowly past a guard of honor and his top aides and general while a military band played. He boarded a helicopter that took him from his compound on to Ponchentong airport, where he took a plane to Bangkok and another to Jakarta.

Was this another bloodless ‘coup’? By getting rid of Lon Nol, were the instigators in the government of the republic trying to buy more time, either for further American aid, or for a diplomatic settlement with deposed Prince Sihanouk in Beijing?

The Khmer Rouge–

It’s easy to think of the ‘Khmer Rouge’ (a term coined by Sihanouk to cover all left-wing groups) as a singular force, but in reality, they were force split into factions of ideology, foreign patronage and loyalties to local commanders. Estimates for the number of combat troops active within the country range from 40,000 to 60,000.

Technically, what are referred to as the ‘Khmer Rouge’ of Pol Pot were only a faction within the National United Front of Kampuchea (FUNK), which had Prince Norodom Sihanouk as its leader.

For the sake of clarity, further uses of ‘Khmer Rouge’, Democratic Kampuchea and Angkar (center/organization) refer to the so-called Pol Pot/Communist Party of Kampuchea.

The Khmer Rumdo were more moderate communists, with links to Hanoi, and Sihanoukists. Mainly from the east of the country, during the early years of the civil war were the dominant military force fighting the FANK. In August 1971, the Khmer Republic official In Tam estimated the non-Vietnamese insurgents to number around 10,000: of these, he was forced to admit that only 4000 were true ‘Khmer Rouge’, the remainder being made up of Sihanoukists and Khmer fighting what they regarded as an “American occupation”. There were several cases, notably around Kampot, where the Khmer Rumdo turned on the more hard-line ‘center’ groups in disputes over rice crop requisitions.

Although many defected after observing the effects of communism in the liberated zones- 742 Khmer Rumdo surrendered en masse to the Lon Nol regime in March 1974- and others were sidelined, commanders still took part in the post-republic Democratic Kampuchea regime. Notable leaders included Hou Yuon (who disappeared in August 1975, presumed killed) and Hu Nim.

The Eastern Zone commanded by Chan Chakrey, who had links to the Khmer Rumdo, commanded the strongest force- Division 170. He was executed in Tuol Sleng Detention Centre in 1976, the first high-ranking official to be sent there. So Phim, the Eastern Zone Secretary, committed suicide.

There were also small elements of the old Thai-sponsored Khmer Issarak movement who had turned to Marxism and also had links to Vietnam. They too were mainly based in the east and had joined with the Khmer Rumdo.

As the ‘Khmer Rouge’ advanced on the city, some divisions began to turn on each other, sometimes out of mistaken identity, and other times due to rivalry between commanders, who had often been running ‘liberated zones’ for several years as fiefdoms.

A former cadre named Van Rith on the system shortly after the Khmer Rouge took power (spellings of commanders differ from usual Anglicized): “The Party enveloped everything, but through a system of fiefdoms, with usurper kinglets (sdech kranh) ruling over each Zone and over Phnom Penh: Mok in the Southwest, Pheum in the East, Koy Thuon in the North, Nheum in the Northwest, Si in the West, each overseeing the economy, politics and executions, “enjoying total delegated authority” (mean seut tâmleak teang âh).”

The most well-known ‘center’ commander was Ta Mok, who had previously used his position in the Southwestern Zone- from southern Koh Kong province to Takeo- to purge rivals, moderates and those thought to have ties with the Vietnamese. Fighters from the Eastern zone- under Chan Chakrey (aka Mean)- and Ta Mok’s Southwestern zone, for example, wore different uniforms (Chinese donated khaki in the east and the better known ‘black pajamas’ in the southwest). They had faced each other off across Phnom Chisor since 1973, following a territorial dispute.

The strangest and perhaps misunderstood were the mysterious Mouvement National ‘MONATIO’ group who appeared spontaneously on the streets of Phnom Penh. Dressed in the black peasant uniform of the ‘Khmer Rouge’ the student group led by Hem Keth Dara were the most photographed by western journalists during the last hours of the republic.

The origins of this sudden seemingly pro-communist group are mysterious- but some believe that they were a ploy by Lon Nol’s brother, Non, to buy favor with the soon-to-be victorious insurgents. Others see the hand of Sihanouk, who perhaps wanted to quietly disarm FANK forces before they could make a last stand, or even as a show of his popularity to his communist allies.

On April 17, Hem Keth Dara, a confessed former ‘playboy’, whose father had been Minister of Information under Lon Nol, ate breakfast with his French wife and two children. At 7 am, he left and met with around 200 followers, dressed ‘in a parody’ of Khmer Rouge fighters. The group moved through the streets encouraging FANK soldiers to give up the fight and lay down their arms, with considerable success. Within 2 hours, with the ‘real’ Khmer Rouge still outside the city, many soldiers, believing peace was at hand tore off their uniforms and the center of town took on what was described as a ‘carnival atmosphere’.

He took up position within the Ministry of Information building and made phone calls to the French Embassy, inviting journalists to interview the new self-proclaimed ‘Commander General of the liberation forces’. By noon the mood had soured as the true Khmer Rouge moved in. 10,000 hungry and tired young men, most no more than 20 years old, many no more that 15, entered the city- a stark contrast to the well fed, fresh faces of the student ‘petit-bourgeoise’ who had imitated their style of dress and made the takeover of the capital a walk in the park, rather than a fight to the death by the defenders.

Who was really behind this organized group, described as acting ‘like traffic police for the Khmer Rouge’ who managed to infiltrate the besieged city and disarm a large number of government soldiers with hardly a shot fired? The answer will almost certainly never be known, as Pol Pot denounced MONATIO as CIA spies. Members, along with the man who ‘liberated’ and ‘ruled’ the country for a few short hours, were swiftly rounded up and executed.

The population of Phnom Penh had swelled to around 2.5 million or more by 1975, as refugees poured into the city to escape fighting in the provinces.

The lack of manpower faced with controlling a huge population was most likely one of the main reasons behind the decision to ‘evacuate’ the major cities. Civilians were told of an impending American counter-attack, and that they were being moved for their own safety. Almost everyone inside the city was forced out into the brutal April heat (the hottest month in tropical Cambodia) and marched to the provinces. Tens of thousands died in the march.

The FANK

The republican army (FANK) were low on both morale and ammunition, and undoubtedly war-weary. Corruption in the higher ranks saw as much as 40% of military salaries being siphoned away, and rumors were rife of weapon and rice sales to the enemy. Desertions were common, with some men switching sides more than once.

A former Khmer Rouge cadre named Chann Sim described his desertions ““Because the Lon Nol soldiers were seriously attacking my division, I decided to work with the free division [he escaped the KR and went over to Lon Nol]. Later, I came back home and I wanted to work with my previous division. But I was arrested because I had worked for Lon Nol. I was starving, and only had watery porridge and sometimes, corn, to eat. I was to fit to that situation, so I escaped from there to another place. When I reached the other place, I was arrested again and accused of being a Lon Nol soldier. So I escaped again. Later on, I joined Division 12. The Khmer Rouge checked me for weapons to make sure that I wasn’t be a spy of Lon Nol’s. But they found nothing, so they believed me. They allowed me to work normally. From that day, I followed the Khmer Rouge guidelines when I worked.”

A peace offer had been cabled, at the behest of Henry Kissinger, to Sihanouk in China 3 days earlier. The deal allowed the unconditional surrender of the Khmer Republic and the invitation for the prince to return as head of state. As word of the offer spread, the was a lull in the fighting on the frontlines. Many FANK units took this to be the beginning of a ceasefire, throwing down their weapons and leaving their posts, further confusing the situation, as crowds thronged the streets chanting “Peace! Peace!” as MONATIO groups encouraged them on.

The offer was soon rejected by Sihanouk, who condemned the ‘traitors’ to death. Leading FANK commanders Sak Sutsakhan- who had been made leader of the republic 5 days earlier- and Air Force chief Ea Chhong left by helicopter for Thailand, and around an hour later General Mey Sichan addressed the nation and the troops in Sak’s name asking them to hoist the white flag as a sign of peace.

There are some accounts that say Lon Non (powerful brother of Lon Nol) had prepared his own division and was about to take advantage of the chaos to seize power, possibly with the aid of MONATIO. He was arrested at the Ministry of Information building and appeared to be quite calm at the time. Was he under the belief he would be spared, even though his name was on the death list? Did he have previous word or a secret deal with the enemy that stopped him from fleeing or putting up a fight?

The Committee for Wiping Out Enemies rounded up key figures within hours. Lon Non was probably executed at Cercle Sportif in Phnom Penh soon after arrest.

Did the commanders and politicians left behind expect to be reprieved by Sihanouk, who was known to change his mind on a whim?

Many of those with high positions within the ‘KR’ were formerly involved in politics, and were closely related to members of the FANK and republican officials. Was there any communication between some of the KR commanders and those of the FANK?

China

From 1970 to 1974, Chinese assistance to the Khmer Rouge was valued at 316 million Iyuan (approximately $632 million in today’s rates *not totally sure). In the same period, the value of Chinese assistance to North Vietnam was 5,041 million yuan (c. $1 billion), or 93.1% of all assistance to the three Indochina countries (North Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia).

Considering that the CCP had been sending aid to Hanoi since 1950, but its assistance to the Khmer Rouge started only from August 1970, it was somewhat ironic that when the Vietnam War finally ended in April, the CCP’s investment in North Vietnam had produced a somewhat troublesome ally with closer ties to the Soviet Union, who were the biggest threat to China. On the other hand, the relatively small assistance that China offered to the Khmer Rouge had created a close ally in Cambodia.

However, after funding various revolutions- Indochina being probably the greatest- and the economic catastrophe following the cultural revolution, China was near bankrupt.

In June 1975, Pol Pot and other Khmer Rouge officials met with Mao in Beijing, where Mao taught Pot his “Theory of Continuing Revolution under the Dictatorship of the Proletariat”, and sent him over 30 books by Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin During the meeting, Mao said to Pol Pot:

“We agree with you! Much of your experience is better than ours. China is not qualified to criticize you. We committed errors of the political routes for ten times in fifty years—some are national, some are local…Thus I say China has no qualification to criticize you but have to applaud you. You are basically correct…During the transition from the democratic revolution to adopting a socialist path, there exist two possibilities: one is socialism, the other is capitalism. Our situation now is like this. Fifty years from now, or one hundred years from now, the struggle between two lines will exist. Even ten thousand years from now, the struggle between two lines will still exist. When Communism is realized, the struggle between two lines will still be there. Otherwise, you are not a Marxist…… Our state now is, as Lenin said, a capitalist state without capitalists. This states protects capitalist rights, and the wages are not equal. Under the slogan of equality, a system of inequality has been introduced. There will exist a struggle between two lines, the struggle between the advanced and the backward, even when Communism is realized. Today we cannot explain it completely.”

Pol Pot is reported to have replied:

“The issue of lines of struggle raised by Chairman Mao is an important strategic issue. We will follow your words in the future. I have read and learned various works of Chairman Mao since I was young, especially the theory on people’s war. Your works have guided our entire party.”

Sihanouk wrote that in August 1975 he, Khieu Samphan, and Khieu Thirith went to visit Zhou Enlai, who was seriously ill. Zhou warned them not to attempt to achieve communism in a single step, as China had attempted in the late 1950s with the Great Leap Forward. Khieu Samphan and Khieu Thirith “just smiled an incredulous and superior smile.” Khieu Samphan and Son Sen later told to Sihanouk that “we will be the first nation to create a completely communist society without wasting time on intermediate steps.“

Following the immediate fall of Phnom Penh, China was one of 9 countries permitted to keep an embassy in the capital- the others being North Korea, Vietnam, Laos, Cuba, Romania, Yugoslavia, Albania, and Egypt. Foreign relations were also maintained with Thailand.

The only airlink to Cambodia was with Beijing, and in August 1975 the first team of experts from the Chinese Ministry of Defence arrived in Phnom Penh followed on 13 September 1975 by General Deng Kun-an, appointed Head of the Chinese Group of Experts. On 12 October 1975, the Deputy Chief of Staff of the People’s Liberation Army arrived in Cambodia. Around 15,000 experts would visit Cambodia over the next 4 years.

Chinese aid continued to flow, with an estimated $1 billion in today’s rates sent in 1975 alone.

Mao died in 1976, and China turned towards a less aggressive foreign policy. Sihanouk also rejected the Democratic Kampuchea government, formally resigning as head of state 5 months before Mao’s death.

The strong nationalism of Democratic Kampuchea meant that Chinese aid, both military and agricultural was mostly kept secret, and any notion that Cambodia would quietly become a vassal state were quickly quashed by the Democratic Kampuchean regime.

Chinese assistance did not help ethnic Chinese and Sino-Khmers during the Cambodian genocide. Labelled as ‘moneylenders’ and ‘capitalists’ the mostly urban dwelling Chinese-Khmer communities were targeted along with Chams and ethnic-Vietnamese. Between 200,000-300,000 were killed between 1975-79- another irony considering that much of the Khmer Rouge leadership were of Chinese ancestry.

Did Mao have plans for Cambodia which were cut short by his death and the internal political problems that came after? Or was he delighted that his infamous ‘cultural revolution’ had born fruit elsewhere?

Cambodia would have been a useful bulwark against Soviet-Vietnamese expansion, but was surrounded by Hanoi backed Laos and Vietnam to the north and east and strongly anti-communist Thailand to the west. Was China already considering an attack on Vietnam from the north – a Chinese navy and amphibious assault had previously seized the Paracel Islands from South Vietnam in early 1974, and an invasion of North Vietnam took place in 1979.

Did China already have plans to use Cambodia as a southern launching pad? The aid sent in 1975 alone was the largest sum to any single country in China’s history- what was in it for the PRC, and why did they not receive any noticeable benefits in return?

North Vietnam

As Chinese aid poured into Cambodia, relations between Hanoi and the Khmer communists began to sour, and by 1973, the North Vietnamese had all but abandoned their former protégé. There were clashes between the groups, around the border areas, but the relationship was, according to Pol Pot, one of ‘Friends with conflict’.

By the end of March 1973, the last American combat troops had been withdrawn from South Vietnam, and on August 15, the last US bomb struck Cambodia, released from a B-52.

The last major offensive undertaken by the south in the Vietnam War was fought between ARVN and PAVN troops in Svay Rieng, from March 27-May 2. and was considered a success for the Saigon government. However, as American support was cut, there were no more operations initiated by ARVN, and Saigon, like Phnom Penh looked doomed to falling from mid-1974.

Why did Vietnamese communists who had been in Cambodia since the end of World War II give up on the country so shortly before the whole of Indochina turned red? Understandably, the key objective was to seize Saigon and thus end the ’10,000 day war’, and so took all the manpower and logistics. Was the threat from China too strong if Hanoi started to meddle in Cambodian affairs before the main war was over?

An attack on the northern border would have had certainly stalled plans for the final ‘Spring Offensive’ of 1975. Had the North Vietnamese given up on Cambodia? This seem unlikely given the risk that the Chinese could be able to operate out of the country. Were the Vietnamese banking on the ‘Hanoi’ faction of the Khmer Rouge to become dominant after the dust had settled? Much of the more moderate member of the Khmer communist movement had received training and support from Hanoi since the 1950’s.

With memories of Kampuchea Krom still fresh, and the annexation of Champa in the still recent past, along with centuries of ‘Vietnamese aggression’, the overwhelming mindset of Cambodians was that Vietnam wanted to dominate the whole of Indochina. This became an obsession for those like Pol Pot and would prove to be a self-fulfilling prophecy, as undernourished, poorly trained and badly equipped Khmer Rouge soldiers- often little more than boys- began attacking Vietnamese civilians and battle hardened PAVN forces days after the fall of Phnom Penh.

A series of provocations against Vietnam would finally end Democratic Kampuchea. Was it these that saw the end of the Pol Pot’s rule, or were the Vietnamese, with their Confucian philosophy of patience and perseverance already planning to take over Cambodia, as was feared?

“To reap a return in ten years, plant trees. To reap a return in 100, cultivate the people.”- Ho Chi Minh.

Thailand

From 1963-73, Thailand had been ruled by Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn, a military dictator who was pro-American and staunchly anti-communist.

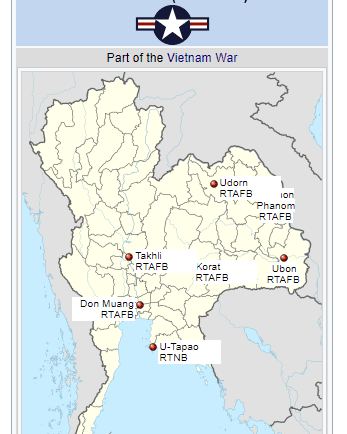

Thailand had committed troops to the Vietnam war, allowed USAF airbases and began the country’s foray into tourism with resorts such as Pattaya developed for off-duty US servicemen on ‘R&R’.

Anti-communist paramilitary organizations such as ‘Village Scouts’ ‘Red Gaurs’ and ‘Naraphon’ under the sponsorship of the royal family were used to fight against Cambodian, Chinese and Vietnamese sponsored Thai communists who had been permitted small bases inside the Cambodian border. They also took harsh reprisals against students.

Student activism, inspired by left-wing ideologies, saw a harsh crackdown by security forces led to the “Day of Great Sorrow” on 14 October 1973.

The popular uprising saw hundreds of thousands take to the streets, and left scores dead as the army fought to keep control.

The new Thai government of Judge Sanya Dharmasakti asked the United States to withdraw its combat forces from Thailand. In March 1975, 27,000 military personnel were authorized for six bases and other facilities throughout the country. By the following July these numbers had reduced to less than 250.

In ‘Operation Palace Lightning’, it was agreed that the former USAF bases, along with hundreds of millions of Dollars’ worth of equipment would be handed over to the Thais.

In April 1975, Thailand was the first country in Southeast Asia to recognize the new regime of the communist Khmer Rouge in Phnom Penh. In October the two countries agreed in principle to resume diplomatic and economic relations; the agreement was formalized in June 1976, when they also agreed to erect border markers in poorly defined border areas.

The subsequent years saw political turmoil, and as fears of a communist Indochina turned into reality, mass panic broke out and the country again switched to the right.

The first refugees from Cambodia began pouring across the border, by 1977 there were some 142,000, according to Lord Elton who raised the issue in the British House of Lords. Hundreds of thousands more would arrive in the early 1980’s.

How much were the Thais willing to turn a blind eye to the actions of Pol Pot’s Democratic Kampuchea, and how much intelligence did they have from across the border? Relations were improving with both China and Vietnam in the years following the American withdrawal, but behind the scenes did King Bhumibol really trust the old enemy of Vietnam, and with Pol Pot in power with the support of China, was it easy to ignore the politics and see Cambodia again as a buffer-zone between the two rival states?

Sihanouk

The man with the most to lose came out of the civil war as both victor and vanquished. He was appointed as Head of State, a ceremonial position in Democratic Kampuchea- a communist country with a monarchy was yet another Cambodian peculiarity. In September 1975, Sihanouk briefly returned to Cambodia to inter the ashes of his mother, before going abroad again to lobby for diplomatic recognition of Democratic Kampuchea.

He returned on 31 December and in February 1976, Khieu Samphan took him on a tour across the Cambodian countryside. Sihanouk saw evidence of forced labor and- no doubt heavily censored- examples of the new domestic regime, named Angkar (the organization), in action. In protest Sihanouk resigned as Head of State, which was initially refused and later accepted in mid-April 1976, retroactively backdated it to 2 April 1976.

Following his resignation Sihanouk was kept under house arrest at the royal palace and later moved to the suburbs. Throughout his confinement, Sihanouk made several requests to the Angkar to travel overseas, which were all denied.

When asked of his allegiance with the Khmer Rouge, Sihanouk told The Washington Post in a 1985 interview in Thailand: “I have only one nightmare about the future of Cambodia, that it could be ‘Vietnamized’ and lost to the Cambodians, that it could become a second South Vietnam.”

Why did Sihanouk repeatedly rebuff negotiations to end the civil war from at least 1973? Did the death of Mao, and his long-time friend Zhou Enlai in 1976 scupper a long-term plan, or had the prince been played?

Family Affairs

The Cambodian civil war was, in many ways, yet another case of ‘history repeating’. Time and time again, conflict in Cambodia had been waged between a small group of elite and blood relatives. Although not unique to Cambodia, such family feuds were certainly particular to the kingdom, examples of which regularly stretch back to the beginnings of recorded Khmer history.

For a hardline Marist group, many in the Khmer Rouge/Democratic Kampuchea leadership came from privileged backgrounds. Some of the better-known examples of this tangled web were:

Sisowath Sirik Matak, who was behind the ousting of Norodom Sihanouk was the Prince’s cousin, likewise Sak Sutsakhan was first cousin of Nuon Chea- aka Brother Number 2, Pol Pot’s right-hand man in the Democratic Kampuchea regime.

Saloth Sar, aka Pol Pot, spent some of his childhood in the Royal Palace with his cousin Meak, who was a ballet dancer and consort of King Monivong. It is also said that aged around 16, Sar gained his first sexual experiences with the palace concubines. There is even a story of the young Sar falling for a beauty queen and minor royal named Somaly/Son Maly, who later left him to become mistress to then Ambassador to Great Britain (and would be assassinator of Sihanouk) Sam Sary- father to opposition politician Sam Rainsy.

Three grandsons of First Minister Veang Thiounn- who served under Norodom, Sisowath and Sihanouk until his death in 1946, went on to hold top roles in Democratic Kampuchea; Thiounn Prasith was representative at the UN, Thiounn Thioeun was the DK Minister of Health, and Thiounn Mumm, a senior scientist at the Ministry of Industry.

Sisters Khieu Ponnary and Khieu Thirith were born into a wealthy Battambang family, with their father a top judge. They would later become leading female members of the communist movement and marry Pol Pot and Ieng Sary.

Prince Norodom Chantaraingsey, a grandson of Norodom and first cousin of Sihanouk’s father, Norodom Suramarit and married to Sisowath Samanvoraphong (one of Norodom’s many daughters, and therefore his own great aunt) was another stranger than fiction character.

As an anti-monarchist Issarak, he had carved out a personal fiefdom in Kampong Speu before being arrested and imprisoned for 3 years for plotting a coup, before being pardoned and given the state casino to manage. After 1970, he returned to his warlord past, controlling the Tiger Brigade in western Cambodia fighting against the communists. One of his chief aides was a man named Saloth Chhay, elder brother of Saloth Sar/Pol Pot.

The modern day Cambodian elite are still made up of closely linked family groups, joined in a complicated system of marriage and patronage.

Will history again repeat itself, or has the cycle of family feuds and internecine violence finally been put to rest after a millennia or more?

Submitted by History Steve (if you enjoy these pieces, get in touch for details on how to buy him a beer).

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own. Cover photo- Roland Neveu

PART 1: End of Angkor- 1800’s

PART 2: The Carved Kingdom

PART 3: French Indochina

PART 4: World War 2

PART 5: Independence to Civil War

PART 6: 1970, A Very Bad Year

Fascinating. Thank you for maintaining the archives.