The turning point for modern Cambodia came in the first half of 1970. A chain of events in Phnom Penh, Beijing, Hanoi, Saigon and Washington had consequences still felt 50 years later.

The Cambodian Coup

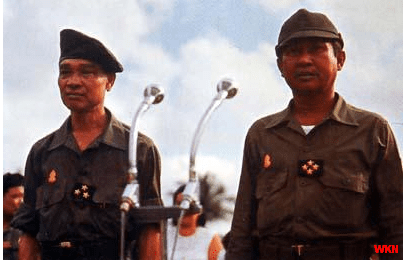

In March 1970, Prince Sihanouk left on a trip to France, the Soviet Union and China. Around halfway through his trip he was removed from office by the National Assembly in Phnom Penh. Later the same year the Khmer Republic was declared.

The motives behind the Cambodian coup of 1970 are still debated. The key plotter Sirik Matak was sent a secret recording of Sihanouk from Europe, on which he said he planned to have him and Prime Minister Lon Nol executed on his return to Cambodia. The prince was ordered to cut his trip short by Sirik Matak, and when he refused, it is said that Matak went to Lon Nol and threatened to shoot him if he didn’t agree to sign papers necessary to begin the process of deposing the monarch.

Lon Nol’s hesitation is seen by some as less than a mere power grab, but an attempt at a wake-up call for Sihanouk to step out of politics. The prince had become unpopular among the middle classes and urban citizens- the country was on the brink of economic ruin, corruption rampant and not only had Vietnamese communists taken over much of the countryside, but American bombing was driving them deeper into Cambodia and even into the larger towns in the provinces.

Nor could the ‘coup d’état’ really be defined as such. With the exception of member Kim Phon, who walked out of the proceedings in protest, the National Assembly voted unanimously to invoke Article 122 of the Cambodian constitution, which withdrew confidence in Sihanouk. Lon Nol took over the powers of the Head of State on an emergency basis. Although the military stood on guard around the capital, there was no army involvement in the vote, nor any violence, and the process undertaken was all done legally following the constitution.

The Queen Mother was forced to leave the royal palace by the new government, and before she was permitted to leave for Beijing in 1973, Lon Nol prostrated himself at her feet and begged her forgiveness.

The Beijing Pact

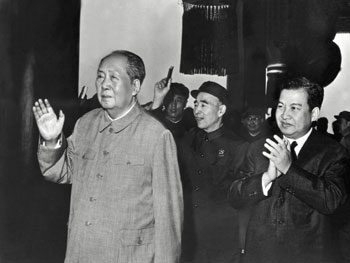

Sihanouk heard the news when in Moscow, and initially began making plans to live the life of an exile in France. Instead he traveled on to China and met his old ally Zhou Enlai. The prince was persuaded to ally himself with his former political foes in the Khmer communist movement.

Sihanouk was not the only important figure in the Chinese capital. In November 1969, an ambitious Khmer communist named Saloth Sâr, aka Pol Pot, had made his way to Hanoi to persuade the North Vietnamese government to provide direct military assistance for his guerilla fighters. Wishing to maintain a relationship with Sihanouk, he was refused, and urged to revert to a political struggle.

In January 1970 he flew to Beijing and was in the city as Sihanouk was deposed. With negotiations between the Cambodians led by China with North Vietnamese Prime Minister Phạm Văn Đồng flown in, Sihanouk agreed to form a resistance movement, the National United Front of Kampuchea (FUNK). However, Saloth Sar’s true position was kept hidden from the prince.

It was a dangerous game of political chess between all parties, who each had a differing agenda.

For the Chinese, Sihanouk was an important ally in Southeast Asia. As a non-communist, his voice could raise issues and support the Chinese cause in international cases, such as at the UN. They were also wary of a North Vietnamese victory, which may come to dominate the region with closer ties to Moscow that Beijing. Supporting Pol Pot’s faction would also help split the Khmer communists and take away some of Hanoi’s influence.

At the same time, China wanted neither another ‘Southern Vietnam’ under American control in Cambodia, nor did it want to risk another battlefield opening up, such as had happened in Korea, drawing America, China and the Soviet Union into open conflict.

For the North Vietnamese Sihanouk’s Cambodia had been a great asset in the wars against the French and Americans, thanks to the bases inside the border and the ‘Sihanouk’ and ‘Ho Chi Minh’ Trail routes which supplied them. A pro-US regime was a threat to the supply bases, and if the US decided to station troops in Cambodia, the PAVN/VC forces could be sandwiched on both flanks. Many of the Khmer communists had been trained and equipped by Hanoi since the 1950’s, so it was most likely assumed that the loyalty would continue, even with more Chinese aid. A restored Sihanouk government packed with communists would be an ideal neighbor for a united socialist Vietnam, and once more a buffer zone between them and Thailand.

Saloth Sar/Pol Pot, to begin with, had very little to bring to the table other than experience of guerilla warfare against the Sihanouk-led Cambodian government. Born in Kampong Thom to a reasonably wealthy Sino-Khmer farming family, Saloth Sar had spent time as a boy in the royal palace with his cousin who was a consort of King Sisowath Monivong. After losing his scholarship in France, Sar returned to Cambodia with communist and nationalistic leanings in 1953 and spent some time with the warlord Prince Norodom Chantaraingsey, He later went to a Viet Minh training camp in the north of Cambodia and was disappointed to find the communist movement was dominated by Vietnamese, with Khmers given menial tasks. Sar worked in the canteen and grew cassava, and met his mentor Tou Samouth. Under Samouth’s guidance, Saloth Sar quickly rose through the movement

Even though he lacked the required degree, Sar became a teacher in Phnom Penh while carrying out underground activities.

After student riots in February 1962, Sihanouk prepared a list of 34 left wing Cambodians whom he invited/ordered to join him in government. Saloth Sar and Ieng Sary, both on the list, refused the invitation and fled to a Viet Cong base in the jungles of Tbong Khmum.

The North Vietnamese offered little support for the Cambodian communists, preferring to keep Sihanouk in power, especially as he swung to an anti-American stance. Spending time in Hanoi, Sar became convinced that to Indochinese Communist Party, dominated by the Vietnamese was planning for a takeover of Cambodia, once the war with the south had been won.

Sar found a sympathetic ear in Beijing when he visited in 1965. There he witnessed the more hardline of Maoism, as de-Stalinization efforts in Moscow looked for diplomatic solutions to the war in Vietnam.

It was perhaps Saloth Sar’s knowledge of Chinese communism that made him useful for Beijing, or perhaps more radical elements within the Chinese Communist Party were keen to push the doctrine of world revolution. It could be that more moderate elements of the CCP believed they could reign in the Cambodian communists once their aims had been met, as the Vietnamese did. And, should the unthinkable happen and a minor communist figure take control of the conservative, still near feudal kingdom, then it would be Beijing who would have leverage over the leadership, not Hanoi and Moscow.

But it was Sar who would benefit most from the deal. His rebel army was small (numbering perhaps 600-1000 men), under-equipped and stuck in jungle hide-outs. An alliance with Sihanouk, and equipment for China would provide him with what he needed to rise above the many other small rebel factions in Cambodia- legitimacy and manpower.

Sihanouk, arguably, had the most to lose from climbing into bed with the communists. There had been no one on the Cambodian throne since the death of Suramarit in 1960. Perhaps, if he had been in Paris, or even Moscow, he could have been persuaded to relinquish his political role and negotiate his return as a figurehead monarch.

But. It was not to be. The coup was seen as a personal affront to Sihanouk, who later described Lon Nol as a “complete idiot” and Sirik Matak as “nasty, perfidious… a lousy bastard”

Civil War Begins

For all his unpopularity in urban areas, Sihanouk had a devoted following amongst the rural majority, for whom life had changed little over the centuries. On March 23 1970, he broadcast a radio appeal urging the population to rebel against Lon Nol. Demonstrations broke out in several towns and were brutally suppressed by the new regime. Thousands heeded the call and left their homes to join the rebellion.

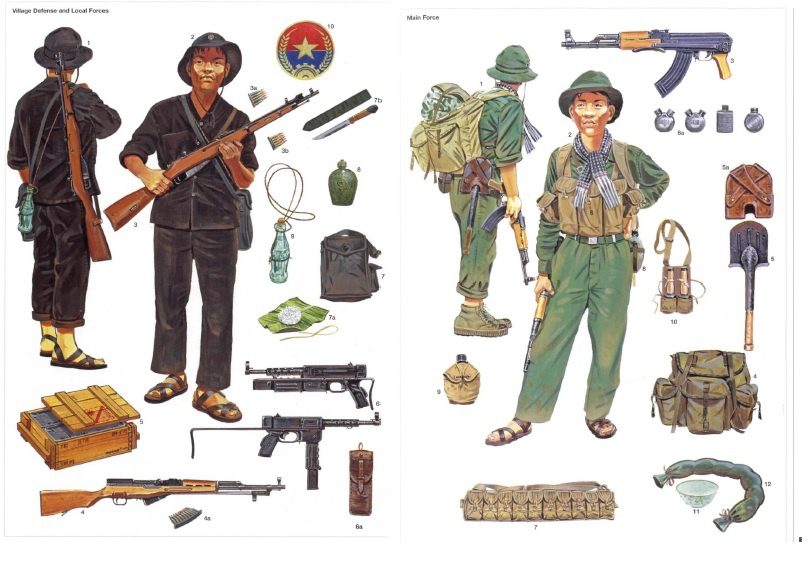

The Khmer army, FANK, was also swelled with volunteers who joined up. The FANK numbers rose from around 35,000 (a requisite of neutrality) to around 150,000 by the end of 1970. Both sides had increased manpower, but the vast majority were untrained farmers or students, and lacking any fighting experience or weapons.

Lon Nol continued to plead for all foreign groups to respect Cambodian neutrality. He began his leadership by appealing to the international community and to the United to condemn violations of Cambodia’s neutrality “by foreign forces, whatever camp they come from.”

It was the North Vietnamese who would strike first, and hard.

Although Saloth Sar had requested the Vietnamese supply only weapons and not soldiers, wanting the struggle to be between Cambodians only, on March 29 1970, the North Vietnamese launched a massive offensive against the FANK. Documents uncovered from Soviet archives later revealed that the Khmer Rouge requested the attack following negotiations with Nuon Chea.

The unprepared FANK had been badly beaten, and almost half the population were living in territory under the control of the Khmer Rouge and North Vietnamese. As noted in the official Vietnamese war history: “our troops helped our Cambodian friends to completely liberate five provinces with a total population of three million people… our troops also helped our Cambodian friends train cadre and expand their armed forces. In just two months the armed forces of our Cambodian allies grew from ten guerrilla teams to nine battalions and 80 companies of full-time troops with a total strength of 20,000 soldiers, plus hundreds of guerrilla squads and platoons in the villages.”

As many as 450,000 ethnic Vietnamese civilians were living in Cambodia in 1970. As the North Vietnamese campaign began many were rounded up and imprisoned, often used as hostages and human shields against PAVN (also known as NVA) attacks. Mass killings took place as Khmers murdered local Vietnamese neighbors, with civilians, police and soldiers taking part in the murders.

On April 18, 800 Vietnamese men were butchered and thrown in the Mekong and floated down the river into South Vietnam. In the 5 months following the coup 100,000 left the country and another 200,000 were forcibly repatriated to South Vietnam.

Both North and South Vietnam protested and Lon Nol stated of the killings that “it was difficult to distinguish between Vietnamese citizens who were Viet Cong and those who were not. So it is quite normal that the reaction of Cambodian troops, who feel themselves betrayed, is difficult to control.”

The Cambodian Campaign

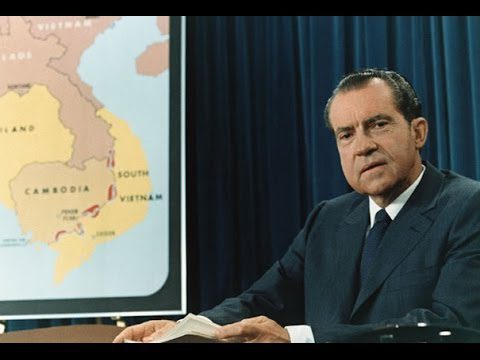

In Saigon and Washington, the Nixon administration was searching for an honorable exit strategy from Vietnam, where over 48,700 American personnel had lost their lives since 1960.

The policy was known as Vietnamization and planned to transfer combat operations over to the South Vietnamese army (ARVN). Cambodia was to be the testing ground for Vietnamization.

On April 20, 1970 President Nixon made a televised address promising that 150,000 troops from the 386,000 in Vietnam would return home by the year’s end.

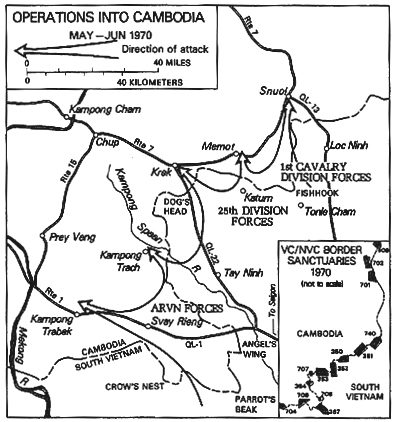

Two days later 22 Nixon authorized the planning of a South Vietnamese incursion into the Parrot’s Beak, an area of Svay Rieng that juts into Vietnam. Nixon justified the decision as “Giving the South Vietnamese an operation of their own would be a major boost to their morale as well as provide a practical demonstration of the success of Vietnamization.”

Nixon also stated “We need a bold move in Cambodia to show that we stand with Lon Nol…something symbolic…for the only Cambodian regime that had the guts to take a pro-Western and pro-American stand.”

On April 25 Nixon dined with his friend George ‘Bebe’ Rebozo and Henry Kissenger. After the meal they watched the classic war movie ‘Patton’, a favorite of the president. The following evening Nixon authorized the action, preparing to “Go for broke”.

The prime objective was to capture or destroy Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN), a mythical command center which controlled Viet Cong operations. The Americans imagined a fixed base staffed with officers and equipment. In reality the COSVN was highly mobile and spread out, with messages transported between bunkers and huts by couriers on bicycle and motorcycle.

In reality the Cambodian Campaign was rushed, poorly planned and ultimately futile. To prevent the details being passed to the enemy, commanders were only given details days before going into battle, the embassies in Saigon and Phnom Penh were left unaware and Lon Nol was not informed of the plan until South Vietnamese troops were already across the border and engaging the PAVN and VC. The Cambodian Prime Minister was informed by a telephone conversation with the US Ambassador, who had only found out after listening to radio broadcasts.

The North Vietnamese were caught by surprise when ARVN troops transported by helicopters crossed the border and surrounded them on April 30. In what would be known as the “Escape of the Provisional Revolutionary Government“, the core of the North Vietnamese frontline fighters including elite units and military leaders managed to break out of the encirclement, and under bombardment from B-52 airstrikes made it to relative safety in Kratie.

The Americans arrived on May 1 in an area known as ‘The Fishhook’ in eastern Kampong Cham province. A week earlier a MACV-SOG team had been inserted to conduct an intelligence gathering operation and came under heavy fire. They were evacuated 7 hours later with the loss of several Americans and Vietnamese Montagnards, including special forces legend Jerry ‘Mad Dog’ Shriver.

10,000 US troops and 5,000 ARVN were sent to the Fishhook, but the bulk of the North Vietnamese force had melted away. A directive uncovered in the operation dated March 17 ordered PAVN forces to “break away and avoid shooting back…Our purpose is to conserve forces as much as we can“.

The town of Snoul, the end point of the Sihanouk trail, was better defended. When infantry and helicopters were fired upon on the outskirts, airstrikes were called. The town was blasted for 2 days, before 1st Battalion (Airmobile), 5th Cavalry Regiment, entered what came to be known as “The City”, southwest of Snoul. The two-square mile PAVN complex contained over 400 thatched huts, storage sheds, and bunkers, each of which was packed with food, weapons and ammunition. There were truck repair facilities, hospitals, a lumber yard, 18 mess halls, a pig farm and even a swimming pool. The one thing that was not found was the COSVN.

Nixon’s ‘knock out blow’ to end the war was deeply unpopular in the United States, and protests against the Cambodian Campaign broke out. On May 4, 4 students were killed and 9 others injured when National Guardsman fired on a student demonstration at Kent State University, Ohio.

To counter public opinion, Nixon issued a directive on May 7 limiting the distance and duration of U.S. operations to a depth of 30 kilometers and setting a deadline of 30 June for the withdrawal of all U.S. forces to South Vietnam.

At the end of the operation, 58,608 ARVN and 50,659 troops had entered Cambodia, losing 638 killed in action/35 missing and 338 killed in action/13 missing respectively.

The U.S. and ARVN claimed 11,369 PAVN/VC soldiers killed and 2,509 captured. 22,892 individual and 2,509 crew-served weapons; 7,000 to 8,000 tons of rice; 1,800 tons of ammunition (including 143,000 mortar shells, rockets and recoilless rifle rounds); 29 tons of communications equipment; 431 vehicles; and 55 tons of medical supplies were captured. Nixon proclaimed the incursion to be “…the most successful military operation of the entire war.“, whereas ARVN General Tran Dinh Tho was more skeptical:

“[D]espite its spectacular results…it must be recognized that the Cambodian incursion proved, in the long run, to pose little more than a temporary disruption of North Vietnam’s march toward domination of all of Laos, Cambodia and South Vietnam”

Aftermath

Lon Nol and his government desperately wanted the Americans to keep a presence inside the country, aware that, although bloodied, the communist forces were far from beaten, and had retreated deeper in order to regroup.

Meanwhile, PAVN/VC units in Laos had actually taken advantage of the distraction and used the time of the campaign to improve and repair sections of the Ho Chi Minh trail.

The withdrawal left a vacuum in the ‘cleared’ zones, which the FANK were unable to fill, and much of the area came under the control of the Khmer Rouge during the monsoon season.

Once more a Cambodian ruler went to Bangkok to seek help against the Vietnamese. This time, after two days of talks with Lon Nol and his delegation in July 1970, the Thais refused to send troops across the border. “The result was zero, absolutely zero,” a member of the Cambodian delegation said on return to Phnom Penh on July 23.

Around 21,000 Thai forces fought in the Laotian civil war in either Kaw Taw paramilitary units or Border Patrol Police Parachute Aerial Resupply Unit (BPP PARU), recruited by the CIA and officially classed as mercenaries. After experiencing the devastating effects of taking on the PAVN on the battlefield, the Thais were unwilling to commit any ground troops to Cambodia unless directly threatened by the communists.

Another reason for holding back may have been to wait to see what the Americans might offer Bangkok in return for further involvement in the war. Washington was, however, against the idea with the State Department citing the lack of Thai military ability in battle, and in a rare acknowledgement of regional history, concerns that Thailand’s past annexations of the northwest could stir up negative feelings among Cambodians.

While ARVN incursions continued along the border, without Thai support, much of the north and west of Cambodia was lost to the Khmer Rouge and North Vietnamese.

Saloth Sar, who by now was going by the name Pol Pot, was one of the biggest winners in 1970. The North Vietnamese began planning for their major conventional invasion of the South, the Easter Offensive of 1972, and much of the daily operations against the FANK were given to the Cambodian Communists.

The Cambodian Civil War would grind on for almost 5 more years, but by mid-1970, Lon Nol’s forces were for the most part confined to the major towns, while the communists controlled vast swathes of the countryside, and perhaps most importantly, the rice fields and agricultural labor.

Cover photo: 31st Engineer Battalion, 1970

If you missed the previous installments they can be found here:

PART 1: End of Angkor- 1800’s

PART 2: The Carved Kingdom

PART 3: French Indochina

PART 4: World War 2

PART 5: Independence to Civil War

One thought on “The Elephant & Dragon 6: 1970- A Very Bad Year”