This is Part 5 in a series looking at how the relationships between Cambodia -Vietnam-Thailand have shaped history. This latest piece roughly covers events from 1947-1970, both inside and outside of the kingdom.

If you missed the previous installments they can be found here:

PART 1: End of Angkor- 1800’s

PART 2: The Carved Kingdom

PART 3: French Indochina

PART 4: World War 2

Post War Democracy

Democracy got off to a shaky start in post-war Cambodia. Two main parties emerged- the Liberals, a pro-French conservative group, mostly supported by the Sino-Khmer business community and old elites who advocated a gradual shift towards independence and close ties with France, and the Democrats, who looked to building a more open society and democratic reforms.

Following the premature death of Democrat leader Prince Sisowath Youthevong, a French-educated aristocrat with a genuine commitment to parliamentary democracy, in July 1947, the elected National Assembly descended into squabbling.

In September 1949, Sihanouk finally intervened and dissolved the National Assembly. Elections were to be postponed indefinitely and government was to be run by a royal council of ministers selected by the king. This was the first time since his coronation in 1941 that Sihanouk had got directly involved in politics. It was not to be his last.

This angered the Democrats and also strengthened the anti-monarchist Issaraks slowly building up forces in the north and west. Political intrigue in Bangkok had weakened the Issarak’s main sponsors from Thailand and the movement split into various factions, including a Hanoi backed communist group. Several of these groups either turned to support from, or came under the direct control of, Viet-Minh agents who were keen to exploit the anti-colonialist feelings in the Cambodian countryside and open up new fronts against the French for the ‘First Indochinese War’.

An important event, or a non-important one depending on one’s point of view came on June 4, 1949. The French, keen to find a solution to end the First Indochinese war agreed to place a united Vietnam, which was before three separate regions of Tonkin, Annam and Cochinchina, as part of the Indochinese Federation along with Laos and Cambodia.

Cochinchina, or Kampuchea Krom (Lower Cambodia) still had a sizable Khmer population, despite hundreds of years of Vietnamese encroachment. The issue is still are sore point today, with some sides claiming the 21 provinces were always Khmer territory and that France had no right to cede them to a new Vietnam, with others saying they had been lost to Cambodia since the 17th or 18th century. In the early 1950’s the ethnic Khmer population in Cochinchina/Kampuchea Krom was around 400,000, compared with some 4 million Vietnamese.

By 1953, with the French bogged down in Vietnam, and under threat of open rebellion from Phnom Penh, Cambodia was given full independence.

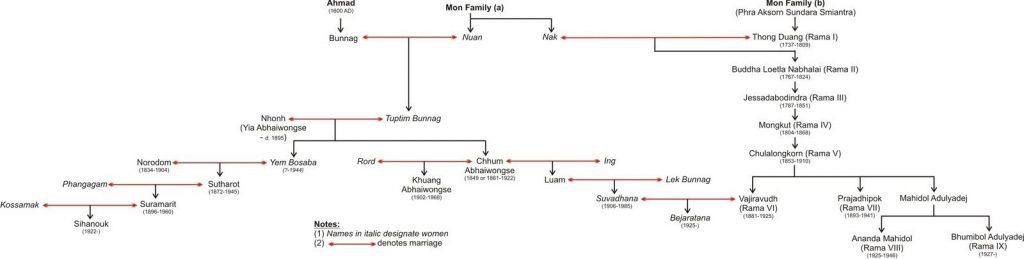

On March 2 1955, in order to go into full time politics, Sihanouk abdicated the throne and was in turn succeeded by his father, Suramarit . In his abdication speech, Sihanouk explained that he was abdicating in order to extricate himself from the “intrigues” of palace life and allow easier access to common folk as an “ordinary citizen”.

In April 1955, Sihanouk formed his own political party, the Sangkum, pulling in support from minor royalist parties. The Democratic Party and other left-wingers refused to merge, and were ousted in the September election. Prince Sihanouk then became Prime Minister, a role he would resign from, and then retake, several times over the next years, swinging from the right to the left and back to the right again.

The Dawn of Independence

The political situation in Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam, along with Korea and China in the immediate aftermath of World War II should be looked at to try to find some context for events that took place following independence up to the Cambodian coup of 1970.

Thailand: Ananda Mahidol, who reigned as Rama VIII, was recognized as the Thai king in 1935, following the abdication of Rama VII and a series of revolutions and coups which ended the absolute monarchy. The choice of Ananda was a convenient one for those in the cabinet who decided on a successor. Aged just 9 years old, the German born prince spend most of his life in Switzerland until December 1945, when he arrived in Bangkok.

Six months later he was found dead from a gunshot wound in his bed. He was aged just 20. The shooting has never been fully explained and the circumstances surrounding the death are still debated today.

In 1950 Bhumibol Adulyadej, Ananda’s brother, 2 years his junior, was crowned as Rama IX.

In theory both King Sihanouk and Bhumibol should have found a great deal of common ground. Both were of a similar age, and came to the throne as young men. They were foreign educated Francophones, Theravadin Buddhists and shared a love for music- especially jazz. If this family tree is correct, the kings were distant cousins.

If there was any hope that there could be a flowering of Southeast Asian democracy similar to European countries such as Britain, The Netherlands and Scandinavia, they would soon be quashed.

With the advancements of education in Siam at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, a version of ultra-nationalist Thai history was written, mostly by the son of King Mongkut Prince Damrong Rajanubhab.

Relying on old folklore rather than fact, he became the key proponent of Suvarnabhumi, the idea of a golden land of ‘Thai’ domination that once ruled over Asia. His writings, dismissed by modern historians, but still important in modern day Thailand, say the Thai people were from Mongolia (possibly due to the might of the Mongol khans) and migrated through Yunnan province. During this supposed ‘golden age’ much of Burma and all of Laos and Cambodia were mere provinces of the Thai race.

Therefore, for much of the 20th century, and perhaps even a notion that lingers today, Cambodia was a backwards region that rejected the superiority of the Thais and suffered for it.

The Thai royal family did, and to an extent still do hold a divine status among the common people, which was carefully crafted by Bhumibol and his court during his exceptionally long reign. Sihanouk, with his interest in directing movies, took a different approach and took to direct politics, casting himself in a ‘man of the people’ role.

The somewhat aloof Thai royal family must also have been somewhat disdainful of the inflated Cambodian royal family, which numbered in at least the high-hundreds or even thousands of minor princes, princesses and hangers on. Many of these were sired through legal marriages with commoners (King Norodom had 47 recognized wives and 61 children, Sisowath had a mere 20, resulting in 29 offspring, this was not counting the royal harem which ran into hundreds of women).

Of this overreaching royal family tree, ‘diluted’ by commoner blood in the eyes of the Thai ‘divine’ nobility, some were little more than warlords (like Prince Norodom Chantaraingsey), while others ran less than regal business operations such as gambling houses and brothels.

The relationship between the two kings was never a warm one. Sihanouk turned up in Thailand ‘on a whim’ and uninvited as he campaigned for Cambodian independence in early 1953 he was received coldly. There were also rumors of a missing gold saxophone, loaned to Sihanouk and never returned. Read the story HERE

Although Sihanouk returned as king of an independent Cambodia the following year and was given a better reception, he never returned on a state visit in his capacity as reigning monarch. 30 years later as the leader of the GRUNK government in exile, the then Prince Sihanouk still grumbled about his treatment by the Thai king.

“During the 1980s, he complained that every time he visited Thailand as President of the Cambodian Coalition Government, he would be made to wait outside King Bhumibol’s office for half an hour or so before seeing the Thai monarch,” his official biographer and confident Julio A Jeldres said. “Once he became King again in 1993, he paid State visits to all of Cambodia’s neighbours, including Malaysia and Singapore, but excluding Thailand”.

The two kingdoms were heading in opposite directions by the time Cambodia was granted independence. Thailand- staunchly anti-communist and pro-American, suffered from political turmoil over the next decades, but Bhumibol forged an image of one above politics (although his hand was often played behind the scenes), and saw himself as a mediator in the numerous coups that affected Thailand during his 70 year reign. Whereas the Thai king saw himself as a divinity, Sihanouk threw himself into the dangerous world of Cold War realpolitik, making friends in unexpected places and more than a few enemies.

Yet, an old dispute was settled in Cambodia’s favor in 1962, when, after hiring U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson to represent Cambodia, the long disputed temple site of Prasat Preah Vihear was recognized as Cambodian territory and given up by Thailand.

Vietnam: Viet Minh guerillas had been operating inside Cambodian territory since at least 1951. In 1953 Viet-Minh troops under the brilliant military tactician General Võ Nguyên Giáp invaded Laos and defeated French forces at the battle of Muong Khoua. Sihanouk took this as an example of a real communist threat to Cambodia when lobbying the French for full independence and made vague threats of an impending uprising in the kingdom.

A few months after Cambodian independence on November 9, 1953, Võ Nguyên Giáp’s Viet Minh forces besieged almost 16,000 French troops, including North African tirailleurs, along with Laotian and Cambodian infantry at Dien Bien Phu.

The siege lasted from March 13 until May 7, 1954 and ended in a humiliating defeat for France. On 8 May, the Viet Minh took 11,721 prisoners, of whom 4,436 were wounded. 8,000 French were marched 500 miles to prison camps; less than half survived. Only 3,290 were repatriated to France four months later.

The Geneva Conference saw an agreement signed on July 21. Vietnam was to be divided at the 17th

Parallel into The Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the north under Ho Chi Minh, and The State of Vietnam in the south first under the man installed by the Japanese, Bảo Đại, and soon replaced by Ngô Đình Diệm. All Vietnamese forces were to leave Cambodia and Laos and respect the neutrality of their neighbors.

Cambodia recognized Hanoi and Saigon, but the relationship would soon sour. Vietnamese communist forces continued to operate inside Cambodia’s borders and Diệm was implicated, along with the Thai government (and rumors of CIA involvement) with the Bangkok Plot of 1959, which attempted to mount a coup against Sihanouk.

Diệm, who some historians say had a deep loathing for the Khmer people, would later complain of the difficulties of working with the Cambodian king describing him as “A self-appointed world statesman”. He claimed that the Cambodians would not consider the instability that would be caused if the North were victorious, and that any attempts to better relations were met with a tirade from the king about the mistreatment of ethnic Khmers in the Mekong Delta. At the same time ethnic Vietnamese inside Cambodia were being killed or forced across the border, something the Cambodian press blamed on the Viet Cong, while Saigon saw it as yet another example of deep-rooted ethnic hatred.

In February 1956, a treaty was signed between Cambodia and China, who promised US $40 million in economic aid to Cambodia. When Sihanouk returned from China, Sarit Thanarat in Thailand and Ngo Dinh Diem of South Vietnam, accused Sihanouk of pro-Communist sympathies. South Vietnam briefly imposed a trade embargo on Cambodia, preventing trading ships from travelling up the Mekong river to Phnom Penh.

Although Sihanouk professed that he was pursuing a policy of neutrality, Sarit and Diem remained distrustful of him, which increased after he formal diplomatic relations with China were established in 1958.

As South Vietnam became more unstable, Cambodia severed diplomatic ties with Saigon in August 1963. The following March, Sihanouk announced plans to establish diplomatic relations with North Vietnam and to negotiate a border settlement directly with Hanoi. These plans were not implemented quickly, however, because the North Vietnamese told the prince that any problem concerning Cambodia’s border with South Vietnam would have to be negotiated directly with the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NFLSVN). Cambodia opened border talks with the front in mid-1966, and the latter recognized the inviolability of Cambodia’s borders a year later.

In June 1969, Cambodia gave recognition to the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam (PRGSV), a shadow communist government. Sihanouk also formally admitted to a North Vietnamese presence inside the country.

Following the death of Ho Chi Minh on September 2, 1969, Sihanouk was one of the few non-communist leaders to attend the funeral.

Korea: Indochina was not the only issue on the table at Geneva. The first major conflict between communists and western powers had raged for 3 years from 1950-53. The war resulted in around 3 million deaths and an armistice agreement split the country, like Vietnam, with a communist north and US-friendly south.

In the south Syngman Rhee ruled an authoritarian and corrupt government heavily reliant on US aid. A coup in 1960 saw General Park Chung-hee take power as an anti-communist military dictator, and although his rule was authoritarian, he oversaw the so-called “Miracle on the Han River” as the country transformed from one of the poorest to one of the world’s largest economies.

Staunchly anti-communist and very pro-west, South Korea would later send over 320,000 troops to fight in Vietnam between 1964-73.

Above the 38th Parallel, former Red Army Major and committed Internationalist Communist Kim Il-Sung ruled supreme. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea was one of the first nations to recognize Ho Chi Minh’s Vietnam, establishing formal diplomatic relations on January 31, 1950. Ho Chi Minh visited Pyongyang in 1957 and Kim Il-Sung went to Hanoi in 1958 and 1964.

The DPRK began by supporting the North Vietnamese, supplying financial aid, weapons, fighter pilots and anti-air forces at the beginning of the Vietnam war, but the relationship became strained from 1968.

In 1964 Sihanouk proclaimed that the DPRK was the legitimate government for the whole of the Korean peninsula, and decided to break off consular relations with the government in Seoul, establishing diplomatic relations with Pyongyang, which was an international pariah, even among non-aligned countries. Kim Il-Sung and Norodom Sihanouk became close in the mid 1960’s, and in a somewhat bizarre friendship, ‘The Great Leader’ built 60 room residence for the Cambodian aristocrat in the hills outside of Pyongyang, where Sihanouk would stay and make movies with North Korean actors. The exiled Sihanouk spent several months a year in this palace while in exile during the 1980’s. He even received the services of heavily armed North Korean bodyguards who accompanied him after 1979.

China: In October 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the People’s Republic of China. Now Ho Chi Minh had a communist ally on the northern border willing to supply arms and equipment to his Viet Minh. The French were no doubt concerned after losing an ally in Chiang Kai Shek, and the potential of the huge Chinese population becoming a fifth column within Indochina.

Chairman Mao, or more specifically his Premier Zhou Enlai, and successors in the PRC would have a massive impact on the history of Cambodia in the years to come.

At the Bandung Conference in April 1955, Sihanouk held private meetings with Premier Zhou Enlai of China and Foreign Minister Pham Van Dong of North Vietnam. Both assured him that their countries would respect Cambodia’s independence and territorial integrity. Sihanouk had either decided, or been persuaded, that the Americans, much like the French, would not remain in the region indefinitely, and Chinese assistance would give protection from the old enemies of Thailand and Vietnam.

The Cambodian and Chinese had mutual interests, with Beijing viewing Cambodia’s nonalignment as vital in order to prevent the encirclement of their country by the United States and its allies.

The loyalty of Cambodian Chinese had long been an issue for the kingdom, and when Premier Zhou Enlai visited Phnom Penh in 1956, he asked the Chinese minority, now numbering around 300,000, to cooperate in Cambodia’s development, stay out of politics, and to consider adopting Cambodian citizenship.

In 1960 the two countries signed a Treaty of Friendship and Nonaggression. As the Sino-Soviet split (1956-66), relations with China increased and cooled ties with Moscow and other Warsaw Pact countries.

In mid-1967, after receiving news that the Chinese embassy in Cambodia had published and distributed Communist propaganda praising the Cultural Revolution inside Cambodia, Sihanouk accused China of supporting local Chinese Cambodians in engaging in “contraband” and “subversive” activities. In August 1967, Sihanouk sent his Foreign Minister, Norodom Phurissara to China, who unsuccessfully urged Zhou to stop the Chinese embassy from disseminating Communist propaganda. In response, Sihanouk closed the Cambodia–Chinese Friendship Association in September 1967.

When the Chinese government protested, Sihanouk threatened to close the Chinese embassy in Cambodia. Zhou stepped in to placate Sihanouk, and a compromise was reached by instructing its embassy to send publications to Cambodia’s information ministry for vetting and approval prior to distribution.

China began looking inwards as the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) took hold, purging many politicians and academics and resulted in the deaths of millions. Zhou himself came under great pressure and the relationship with Sihanouk’s Cambodia waned. At the same time Mao’s increasingly extreme ideology was being exported to a small and relatively insignificant group of communists operating in northern Cambodia, which was trying to break free of Vietnamese control- The Communist Party of Kampuchea, which Sihanouk referred to as ‘Khmer Rouge’.

The USA: The United States recognized the Kingdom of Cambodia, still part of the Indochinese Federation in 1950. In May, President Harry Truman approved $20 million in economic and military aid, an amount that would increase significantly over the decade.

After meetings in Paris, Sihanouk arrived in the USA on April 17, 1953. In meetings with John Foster Dulles, US Secretary of State, the king was told, while the US supported independence for his country, the threat from communism was too great, and Cambodia would be overrun should France withdraw.

Undaunted, the king used the American press, giving a lengthy interview to Michael James of the New York Times, published on 19 April 1953.

“Norodom Sihanouk, King of Cambodia, one of the three associated States of Indo-China, warned in an interview yesterday, that unless the French give his people more independence in the next few months, there is a real danger that the people of Cambodia would raise against the current regime and form part of the Vietminh movement lead by the Communists.”

Post-independence, in February 1955, John Foster Dulles visited Phnom Penh (the highest level official visit at the time) to meet with King Sihanouk and discuss defense plans. A military defense agreement was signed in May.

A United States Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) was established in Phnom Penh to supervise the delivery and the use of equipment that began to arrive from the United States. By the early 1960s, aid from Washington constituted 30 percent of Cambodia’s defense budget and 14 percent of total budget inflows. US aid totaled over $400 million between 1955 and 1963 (around $3.5 billion in today’s terms).

Relations with the United States were often strained. American officials underestimated the prince (following his abdication to enter politics) and considered him to be an erratic character with little awareness of the threat posed by Asian communism. Sihanouk in turn deeply mistrusted the intentions of the US towards Cambodia, especially with the close ties enjoyed between American military advisers and high-ranking, right-wing officers within the Cambodian armed forces.

There were problems in 1958, when Cambodia set up formal ties with China and in 1965 Cambodia broke off diplomatic relations for the next four years.

Sihanouk also suspected Washington’s hand in the ‘Bangkok Plot’ to overthrow him in 1959, and also made accusations that the US was covertly funding the anti-monarchist rebel Khmer Issaraks on the Thai border and Khmer Serei operating out of Kampuchea Krom.

The Bangkok Plot, also known as the “Dap Chhuon Plot” was allegedly initiated by right-wing politicians Sam Sary, Son Ngoc Thanh, the Siem Reap based warlord and governor Dap Chhuon, and the governments of Thailand and South Vietnam with possible involvement of US intelligence services.

In January 1959 the plotters met in Bangkok. Chhuon, from his base in Siem Reap woulkd seal off the Western provinces and declare an autonomous zone, while Son Ngoc Thanh would carry out guerrilla operations throughout the country. The Thais and South Vietnamese would move troops to the borders, and if Sihanouk did not see reason and appoint Thanh to head a pro-Western government, he would be overthrown.

The intelligence services of France, the Soviet Union and China immediately informed Sihanouk of the conspiracy. Cambodian security forces moved in on February 21, 1959. Sam Sary fled to Thailand where he was given refuge by the Thai military, before he disappeared in mysterious circumstances in 1962.

Son Ngoc Thanh also escaped, but Dap Chhuon was later apprehended in Siem Reap, interrogated, and died “of injuries” in unclear circumstances before he could be properly interviewed. Sihanouk later alleged that his Minister of Defence, Lon Nol, had Chhuon shot to prevent being implicated in the coup. Images of his bloodied body were posted on the streets of Phnom Penh.

Inside his villa were 270 kilos of gold bullion, supposedly for paying bribes to local officials when the plan got underway. A radio transmitter with two Vietnamese technicians and an attaché from the US embassy named Victor Matsui were also found on the property. The Americans later explained that Matsui had merely been keeping the embassy informed, but could not say why, unlike other countries, had not forewarned the Cambodians.

On August 31, 1959, a bomb concealed in a case blew up inside the royal palace. Norodom Vakrivan, the chief of protocol, was killed instantly when he opened the package. Sihanouk’s parents, Suramarit and Kossamak, who were sitting in another room not far from Vakrivan, narrowly escaped unscathed.

An investigation traced the origin of the parcel bomb to an American military base in Saigon. While Sihanouk publicly accused Diem’s brother and advisor Ngo Dinh Nhu of being behind the attack, he secretly suspected that the U.S. was also involved.

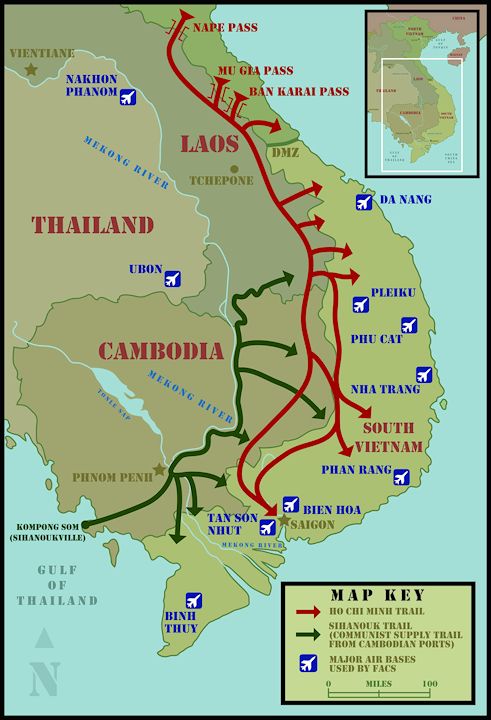

As part of the agreement over Chinese aid to Cambodia, arms and supplies were permitted to travel across the country into South Vietnam to supply communist forces. An arrangement was also struck between the prince and the North Vietnamese government. In October 1965 military supplies were shipped directly from North Vietnam on communist-flagged (normally Eastern bloc) ships to the Cambodian port of Sihanoukville. The nation’s neutrality guaranteed their delivery. The supplies were unloaded and then transferred to trucks which transported them to the frontier zones that served as People’s Army of Vietnam and Viet Cong base areas. These sanctuaries inside Cambodian territory gave the communist forces a place to regroup, rest and rearm before crossing over into South Vietnam to fight again.

American intelligence was well aware of the ‘Sihanouk Trail’ along with a route that cut down through Laos and into northeastern Cambodia- the ‘Ho Chi Minh Trail’. At its peak in 1968, around 80% of all supplies reached the PAVN/VC were being delivered along the Sihanouk Trail

In April 1967 the U.S. headquarters in Saigon finally received authorization to launch Daniel Boone, an intelligence gathering operation that conducted by the secretive Military Assistance Command, Vietnam Studies and Observations Group or SOG.

Under strict instructions not to engage with any PAVN/VC forces, reconnaissance teams “hopped the fence” across the border and began collecting intelligence on North Vietnamese activity inside Cambodia. The results led to Project Vesuvius, where the gathered intelligence was presented to Sihanouk as clear evidence of PAVN/VC violations of Cambodian neutrality.

With Chinese support waning as Mao Zedong launched his Cultural Revolution, and faced with the reality that large swathes of ‘neutral’ Cambodia were now under the control of Hanoi, Sihanouk swung to the right, purging many prominent left-wing politicians from his administration. Several, such as former ministers Hu Nim, Hou Youn along with Khieu Samphan fled to the jungles and joined up with Khmer Rouge groups.

On July 2, 1969, formal relations were reestablished between Cambodia and the United States months after covert bombing along the Cambodian-Vietnamese border began.

In March 1970, large-scale anti-Vietnamese demonstrations erupted in Phnom Penh while Sihanouk was away touring Europe, the Soviet Union and China. The crowds got out of control, although it has been suggested that the government, or even Sihanouk were behind the protests in an attempt to gain leverage over Hanoi.

By the 18th, the National Assembly voted to depose Sihanouk and create a new Khmer Republic. The US has always denied any involvement in the coup, led by pro-American Prince Sisowath Sirik Matak and Prime Minister Lon Nol, but were no doubt pleased to have Cambodia join the fight against the communists.

Now Cambodia was being drawn into the conflict in Vietnam and, when on the advice from China, Sihanouk allied himself with the Khmer Rouge, the Cambodian civil war began.

*Cover photo: funeral procession of King Suramarit, April 1960, Milton Osborne.

Bravo, very interesting!

What ,” Bravo ” to war ,a celebration of war ? War no good ,we like peace thanks- you.