This is Part Three in the series exploring the history between Cambodia and neighbors to the east and west. Part One can be read HERE Part Two HERE

French Cambodia (1886-75)

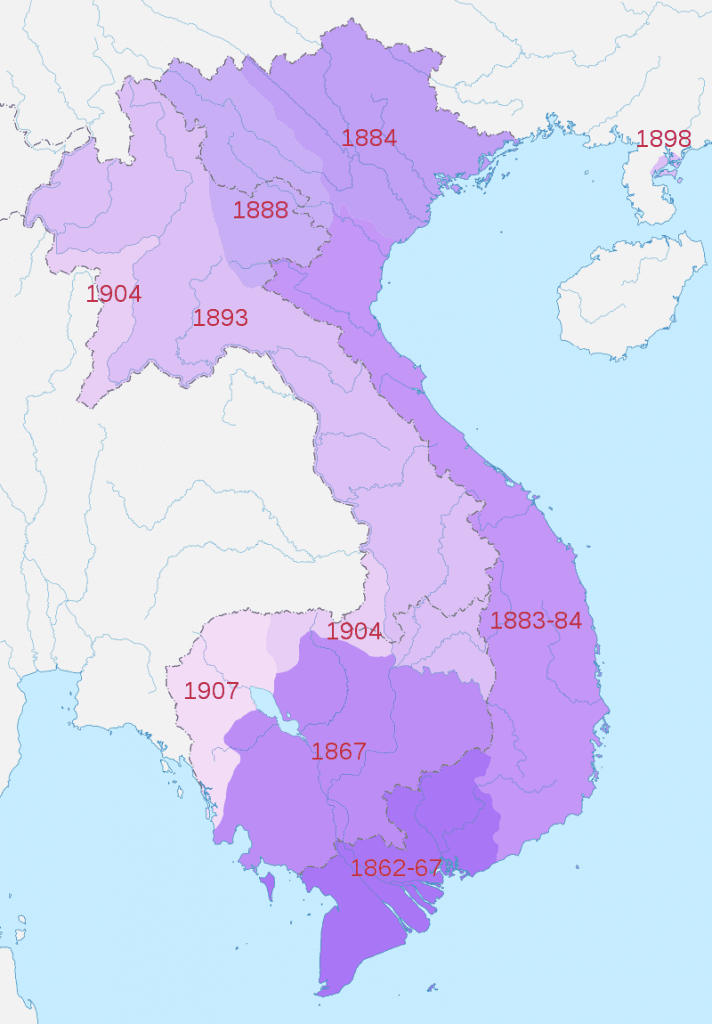

Cambodia, now under French protection, was soon discovered to be of little value to the Empire colonial français once the Mekong expedition of 1866–1868, under the leadership of captain Ernest Doudard de Lagrée, reported back that the river was unnavigable. Upstream of Kratie were the Sambor rapids, the Prépatang and the Khone Falls in southern Laos, where at the Si Phan Don Islands (known now as Don Det and the 4000 Islands) the river split into numerous channels with formidable rapids and waterfalls.

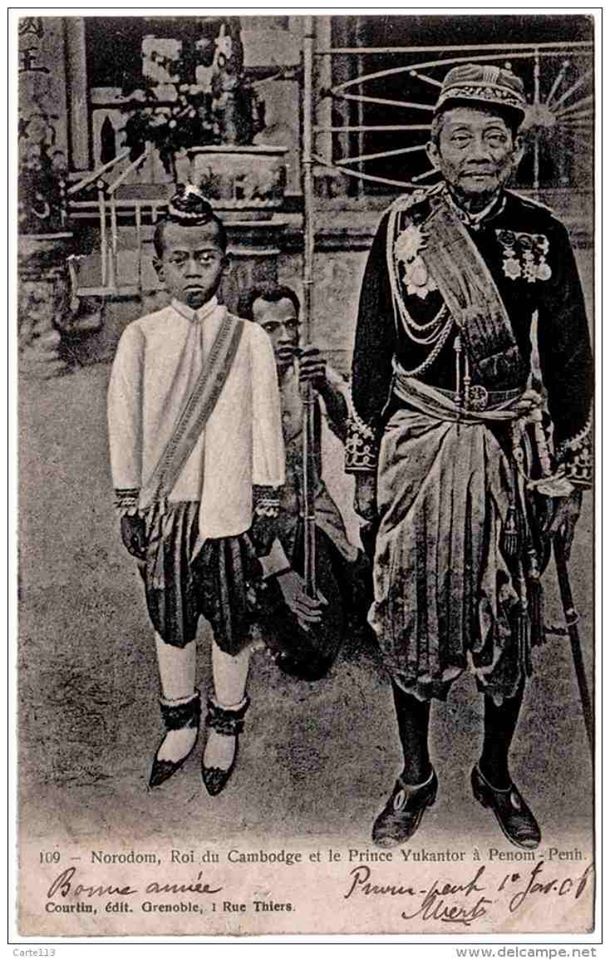

King Norodom was mostly left to his own devices for the first two decades of the protectorate, which, according to French commentators, consisted of his fondness for opium, women, dirty jokes and gaudy fashion sense. Notre roitelet ‘our little king’, as he was referred to by the Europeans, had less interest in ruling his country, exasperating French officials who said of him “‘Without aim and purpose, he pushes ahead but does not wonder where he is going; undecided about everything, of a marvelous duplicity, caprice serves as his only guide”.

The French also recorded how indigenous tribes were being enslaved in the northeast, state officials went unpaid and resorted to plundering from the peasantry, Norodom’s funding of his expensive tastes drawn directly from the state revenue, and his harem of over 400 women. This was at total odds to the mission civilisatrice that was core to the newly established Third Republic in Paris.

The Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71 had seen the end of Napoleon III’s Second Republic, but following the Treaty of Frankfurt, a new scramble for colonies across the globe began in earnest.

Reforms (1875-80)

A new uprising against Norodom broke out in 1875, headed again by his wayward half-brother Si Votha, who had been free and biding his time since his last rebellion had been put down by the Siamese in 1862. This time there was no help coming from Bangkok, and with the situation becoming critical, Norodom finally asked for French assistance in 1877.

The French, although previously agreeing to protect the king ‘from his enemies’, decided to place some terms on Norodom in return for military support. Norodom agreed to allowing a French résident to sit with the council of ministers as a ‘consultant’ on issues of trade, finance and the legal system and any other matters he deemed important. Slavery was to be abolished in stages, and no new taxes were to be imposed without France’s approval.

Norodom agreed and the rebellion was quashed by French and Vietnamese troops. The rebellious prince Si Votha once again disappeared when faced with a superior foe, ready to fight another day.

Soon, living up to his reputation of ‘marvelous duplicity’ the king tried to find ways to get out of the deal. The French then discovered Norodom had been holding secret talks with the Spanish consulate in Saigon- a total breach of the agreement.

The French administration in Saigon discussed removing the king and exiling him to a far-flung corner of the empire, such as Tahiti or Mauritius. However, they recognized the almost Godlike status held by a Cambodian king over the peasantry, no matter how cruel or inept he may have been.

Instead, Vietnamese were encouraged to cross the border and settle with the hope that they may become the majority of the population within a few generations. The idea of “silkworms eating the mulberry leaves” lived on, and continued to cause resentment in the eastern provinces.

More French Powers (1882-93)

A new governor had arrived in French Cochinchina in November 1882. Charles Antoine Francis Thomson, the son of an English father and French mother was born in Algeria and had a background in finance and administration as a préfet in France. Part of his mandate involved recuperating some of the costs incurred by protecting Cambodia.

Thomson arrived in Phnom Penh unannounced one night in June 1884 with three gunboats which moored alongside the Royal Palace. He told Norodom that France intended to collect excise duty on all alcohol and opium sales. The king reacted badly and refused to speak with Thomson.

Later, with the gunboats trained on the palace and marines securing the surrounding street, Thomson and his military aide Captain Joseph Jarnowski burst into the king’s private chambers without appointment and read to him the new agreement between France and Cambodia. Along with the tax reforms, a new Résident-general would oversee the council of ministers, with other residents to be placed in the provinces. Slavery was to be abolished, private property rights for citizens be permitted and that all future ‘reforms’ submitted be approved without question. A furious Norodom was left with no option but to sign.

Six months later another rebellion broke out with Si Votha as the chief instigator, but this time against the French. Support came from the local oknhas (lords), peasants, Chinese merchants who were losing their trade to French levies and a strange mix of Buddhist ‘end of the world’ cults. In March 1885, a rabble army around 5,000 strong almost succeeded in storming Phnom Penh. The French and Vietnamese auxiliaries were forced back into garrisons and defended outposts.

Si Votha reached out to his half-brothers Norodom and Sisowath. While the king remained suspiciously silent, Sisowath sided with the French. Thomson was called back to France in July 1885 and replaced by acting-governor Brigadier General Charles Auguste Frédéric Bégin, a military man who disapproved of his predecessor’s policies. Thomson technically held his position until March 1886, but did not return to Indochina. Bégin wrote of the situation:

“Norodom was humiliated and abused. A very hard treaty was imposed on him by force… The Queen Mother, for whom he professes deep respect and filial piety, would not have not forgiven him for accepting without struggle the humiliation we imposed … even admitting the implicit guilt of the King, one cannot think now of deposing him. We must avoid touching the edifice, because the mandarins will take the opportunity to again push the people to revolt, telling him that we want to overturn everything … We must live with the evil and avoid any further irritation … The first requirement is to place beside the King, both in Cambodia and in Cochinchina, men who did not take part in the events of 17 June. Norodom will never pardon Mr. Thomson for having humiliated and abused him in the presence of his Ministers and of his Court.”

Bégin, who later became commander in chief of troops in Indochina, recruited Cambodians to form a regiment of colonial soldiers.

Brutal reprisals were delivered by both sides. The rebels slaughtered ethnic Vietnamese while the French killed indiscriminately.

A Corsican civil servant by the name of Ange Michel Filippini was sent to resolve the tenuous situation which had also spread to French controlled Vietnam. It was agreed with Norodom that France would respect the autonomy of the king’s administration and cut back the number of French officials in the kingdom. In return, Norodom called for a ceasefire and arranged a general amnesty for the rebels. The main rebel commanders had ceased fighting by the end of the year, with Si Votha fleeing to the northeast. It is estimated that around 20% of the Cambodian population were killed during the almost three years of fighting.

The relationship between the protectors and the protected became estranged for the last years of the 19th century, with France turned attention north and west, annexing the Tonkin region of Vietnam and coming into direct conflict with Siam over Laos in the Franco-Siamese War of 1893.

The peace settlement between the defeated Siamese and French, along with ceding Laos, demanded that Siamese troops leave the provinces of Siem Reap and Battambang, and the French were to occupy the Siamese provinces of Trat and Chanthaburi. Territory swallowed by Cochinchina was notably left off the agenda.

In 1904 Norodom died after a reign spanning 43 years and 188 days. His own choice for heir, the eldest of his sons, Prince Yukanthor, had caused quite a scene on a trip to Paris, and was cast aside in favor of Norodom’s half-brother Sisowath.

The Yukanthor Affair (1900)

Yukanthor, a former child monk, was afraid of new Cambodian middle class rising with the French as a threat to royal power. He first got into a disagreement with a soldier, Lt. Radisson, who was accused of stealing one of Yukanthor’s concubines. The woman in question had been sold to the Prince by his father to pay off a gambling debt.

Norodom sent his son to France in 1900, where he met the left-wing, anti-colonialist French journalist Jean Hess and became an influential figure in Parisian society. He was invited to many parties and dinners in which he expressed his views on French colonialism, even having to flee to Brussels at one point in what became known as the Yukanthor Affair.

During an interview with Hess, Yukanthor spoke about the French government and the French public, and the colonial domination of his country, which was published in Le Figaro newspaper.

Yukanthor’s accusations were that the freely asked and granted protectorate of Cambodia had become a complete French colonial administration, that Norodom was forced to give up his power at gunpoint in 1884, that he was treated terribly by a Frenchman named de Verneville who was involved in a sex scandal when he abused his mistress. He claimed that the Norodom dynasty had “reigned for 3,000 years and has always cared for its people“, and that the Cambodian “had become to slave inside the whims of (French) administrators“.

In the letter sent to Le Figaro, Yukanthor said that there were two types of Frenchmen, those in Metropolitan France and those in the colonies, that the French knew “nothing about the Cambodians and believe we are barbarians“, that “France wants to impose its civilization, but my family has ruled over the Kingdom for thousands of years“, that labor should not be a punishment for sins, that Buddhism made the King the father of the people and Cambodians form a united family, that “we have our ‘slaves’, but your workers have the freedom to starve…. you make an ostentatious display of items of destruction in universal exhibitions“, and that when Norodom asked for French protection, he did not ask for administration or civilization.

Finally, the French banished the prince and he spent his last years in Bangkok, after marrying his half-sister. After hearing Norodom had appointed Prince Yukanthor, as heir apparent, Governor General Doumer threatened to instantly dethrone him should he take the position.

Return of Angkor (1904)

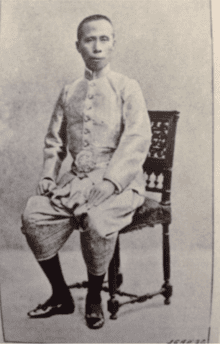

With Sisowath placed on the throne, the highpoint of his reign was the return of the northwest by Siam to Cambodia. The Franco-Siam Treaty signed 23 March 1907 saw the swapping of regions with a Khmer majority (Koh Kong, Battambang, which was much larger then, along with Siem Reap) and those with a majority Thai speaking population (Trat and Chanthaburi in the west and Dan Sai in the north).

French archeologists were fascinated by Angkor Wat, a place litle recognized or understood by the majority of Khmer people at the time. Studies were carried out by the French School of the Far East (École française d’Extrême-Orient), founded in 1900 and based in Hanoi.

In his posthumously published work Voyage dans les royaumes de Siam, de Cambodge, de Laos et autres parties centrales de l’Indochine (1863) French naturalist and explorer Henri Mouhot wrote of Angkor:

“One of these temples—a rival to that of Solomon, and erected by some ancient Michael Angelo—might take an honourable place beside our most beautiful buildings. It is grander than anything left to us by Greece or Rome, and presents a sad contrast to the state of barbarism in which the nation is now plunged.”

At Angkor Wat, men such as Jean Commaille (who was murdered by bandits while carrying his worker’s wages), Henri Marchal, Georges Trouvé – who also died tragically in 1935, Jacques Lagisquet and Maurice Glaize dedicated themselves to uncovering the forgotten temples, documenting and translating the finds that they made.

Such scholarly interest was, in part, responsible for putting the otherwise backwater colony of Cambodia onto the international map. In other ways it was also responsible for an era of Khmer national pride, and arguably the beginning of modern-day Cambodian identity. One such example is that of Jayavarmna VII, whose reign of 37 years had been totally erased, until the work of Georges Maspero who translated inscriptions in southern Laos and ‘discovered’ his legacy. Now the image of the king is ubiquitous and is a national hero.

The past glory of Angkor later became useful for the French as they tried to isolate Cambodia from the rising tide of Vietnamese nationalism and forging a sense of Khmer identity, which had been lost after centuries of subjugation.

Although development of Phnom Penh into ‘the pearl of the east’ progressed, little was done outside the main cities. Some crops, such as rubber, were planted, but the average Cambodian peasant, who paid the highest taxes in Indochina, saw very little return.

This can partly be blamed on the conservative culture of Cambodia, which despite French reforms, remained almost feudal in the countryside. Buddhist monks, who were the sole educators, resisted modernizing the traditional school system.

Education (1872-1936)

Meanwhile upper-class Siamese students had been attended Oxford since the university opened up to ‘non-Anglicans’ in 1872. Many had studied at British schools before university, following Rama IV’s desire for the young elite to receive a western education. In 1921, under the reign of Rama VI, the Compulsory Primary Education Act became law, requiring compulsory four years of schooling. The king himself had studied law and history at Christ Church, Oxford in 1899, where he was a member of the exclusive Bullingdon Club. However, he suffered from appendicitis, which treatment barred him from graduating in 1901. More Thai Oxford Old Boys can be seen HERE

French efforts at education in Vietnamese provinces during the early decades of colonial rule were negligible. A few government quoc ngu schools were established along with an Ecole Normale to train Vietnamese clerks and interpreters. A few Vietnamese from wealthy families, their numbers rising to about ninety by 1870, were sent to France to study. Three lycees (secondary schools), located in Hanoi, Hue, and Saigon, were opened in the early 1900s, using French as the language of instruction.

“Educated Vietnamese“, declared the Résident-supérieur of Tonkin (northern Vietnam), “[are] revolutionaries and malcontents, detached from their culture, the rice field, and the artisan’s shop“.

The number of quoc ngu elementary schools was gradually increased, but even by 1925 it was estimated that no more than one school-age child in ten was receiving schooling. Vietnam, which under the old dynasty system had a high rate of literacy, saw the rate reduce massively during the colonial period.

The University of Hanoi, founded in 1907 to provide an alternative for Vietnamese students beginning to flock to Japan, was closed for a decade after just one year due to fears of student involvement in a 1908 uprising in Hanoi. In Tonkin and Annam, traditional education based on Chinese classical literature continued to flourish well into the twentieth century despite French efforts to discourage it. The triennial examinations were abolished in 1915 in Tonkin and in 1918 in Annam. China, which had always served as a source of teaching materials and texts, by the turn of century was beginning to be a source of reformist literature and revolutionary ideas.

As Siamese education modernized and French controlled Vietnam stalled, or slid backwards, Cambodia saw little change up until the 1930’s. Only seven high school students graduated in 1931, and between 50,000 to 60,000 children were enrolled in primary school in 1936.

The Colonial Facade

Nevertheless, the bureaucratic system needed workers. The total number of “Europeans and assimilated races” (which included French, nationalities from French colonies such as Madagascar and French West Indies, Americans and naturalized local wives and offspring of colonialists) in Indochina was around 24,000 shortly before the outbreak of World War 1. Of these, only around 10% were Fonctionnaires (Civil servants), the clerks and low-level administrators were mostly Vietnamese.

It was the norm rather than the exception for the average Khmer farmer living outside of a town to pay taxes to France, send products to the French and require French stamps and seals for all manner of documents yet never see a European. The face of the often-contemptuous bureaucrat, who imposed the rules and took the bribes, was more often Vietnamese, thus continuing the animosity felt by average Cambodian towards ‘the yuon’.

(*Note on the word ‘yuon’: the term was first used to describe Vietnam and Vietnamese over 1000 years ago, both by Khmer and Cham. The word ‘Vietnam’ only entered the Khmer lexicon in the 1970’s. Since then, ‘yuon’ has been labelled racist, but is still used by ethnic Khmer speakers in southern Vietnam without causing offence.)

One overzealous Frenchman named Felix Bardez, the résident for Kampong Chhnang found out the hatred for the colonial tax collectors when he was murdered in Kraang Leav in 1925. Bardez had ordered the round-up of three village elders and informed villagers they would not be released until all back taxes had been paid. Things turned sour and Bardez, along with several of his militiamen were beaten to death by an angry mob. The village was renamed by Sisowath to Derichhan, or “bestial”– an especially offensive word in the Khmer language, and still to this day residents are sometimes called ‘beasts’.

World War I

World War I saw the call to arms expand to Indochina. Around 2,000 Cambodians and 90,000 (other sources give numbers up to 140,000) Vietnamese went off to fight. Five Cambodian princes, three of them grandchildren of Norodom, the other two grandchildren of Sisowath were among those to enlist. The majority were employed behind the lines in guard, depot and factory-worker duties. However, several battalions fought at Verdun, the Chemin des Dames, and in Champagne. Some Indochinese troops were also deployed to the Macedonian front.

Communism Arrives

Also in Europe at the same time was a Vietnamese socialist kitchen hand called Nguyễn Sinh Cung, later to go by the name of Ho Chi Minh.

Returning troops brought back new ideas, some of them anti-colonialist and others more radical. The inter-war years saw moderate French reforms in Indochina, but Vietnam was plagued by strikes, bombings and open rebellion. Siam also saw military coups and a brief civil war. After a royalist rebellion was put down in 1933, the leader Prince Boworadet sought asylum in Cambodia, where he lived until 1948. Yet, for the most part Cambodia remained quiet and peaceful and French protection had prevented any more .

In October 1930, a secret meeting was held in Hong Kong at the behest of Moscow. Ho Chi Minh was told by his Soviet sponsors that his growing Communist Party of Vietnam to include Laos and Cambodia, so the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) was formed. The manifesto was:

1. To overthrow French imperialism, feudalism, and landlordism.

2. To establish a government of workers and peasants.

3. To confiscate all landed properties belonging to foreign or indigenous landlords and to various religious organizations with the goal of distributing them to middle and poor peasants and to make the government of workers and peasants their rightful owner.

4. To appropriate all properties belonging to foreign capitalists.

5. To abolish all present duties and taxes and, at the same time, set up a progressive tax system.

6. To initiate the institution of an eight-hour working day and, therefore, to improve the living conditions of the workers and poor people.

7. To make sure that Indochina is fully independent and the people endowed with self-determination.

8. To create an army of workers and peasants.

9. To implement equality of the sexes.

10. To support the Soviet Union, to ally with all the proletarian classes of the world and with the colonial and semi-colonial revolutionary movements.

The following year there were around 64,000 members and revolt broke out. By August 1931 the communists were crushed, with around 10,000 killed and 50,000 deported by the French. On December 17 Governor-General Pasquier announced that Communism had disappeared from Indochina.

Events in Europe and across the East China Sea would change everything.

2 thoughts on “Between The Elephant And Dragon Part 3: Indochina”