This is Part Two in the series exploring the history between Cambodia and neighbors to the east and west. Part One can be read HERE

*Author’s note: Sources for this period improve, but as always can differ sometimes in spelling of names and places, along with exact dates. This was a busy time in the region, so some details have been left out or only covered briefly.

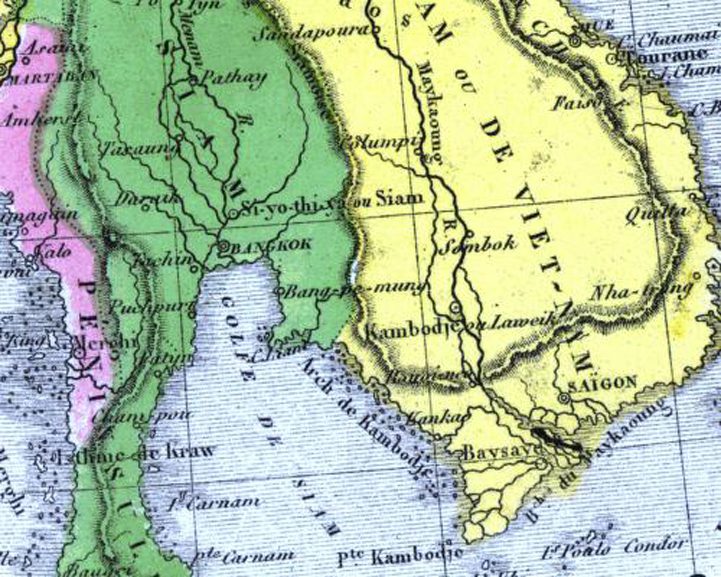

The beginning of the 19th century saw Cambodia carved up between the Siamese in the north and west and the Vietnamese in the east. The Siamese, more closely related to the Khmers through Buddhism and generations of mixed marriage, allowed Cambodian customs to continue, while the Vietnamese, although holding a culture of Confucianism, granted their protectorate a deal of autonomy.

New Emperor, New King, Old Rivals (1820-28)

This relative peace was again shattered in the second decade of the century, as first, Emperor Minh Mang took power in Vietnam, followed by Rama III to the west in 1824.

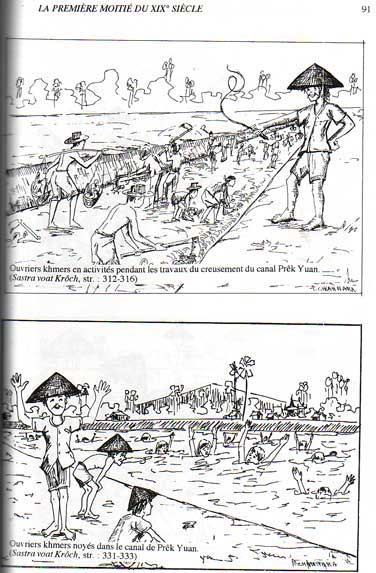

A major rebellion against the Vietnamese came after work began on the Vinh Te canal in 1820. Linking Ha Tien to Chau Doc around 70 km away, this project would enable farmers to drain swamps and provide more agricultural land.

As the project would run through Khmer-populated areas, King Ang Chan was consulted, and the work force was agreed to be made up of equal numbers of Khmers and Vietnamese, since both would reap the future benefits.

There appears to have been some cultural differences as work progressed, with the Vietnamese Confucian philosophy of hard work for the greater good and future rewards coming up against the more personal outlook of Khmer farmers who followed Theravada Buddhism.

Despite pleas from Minh Mang, resentment between the groups intensified and the Khmer workers kept deserting, while Vietnamese officials became more heavy handed. Vietnamese complained that the Khmer workers were lazy and unreliable, and the Cambodians that the Vietnamese were arrogant and cruel.

As animosity grew, a mystic former monk by the name of Kai declared himself the true king and took a rabble of peasant followers on a rampage across Eastern Cambodia, massacring Vietnamese wherever they were found. A Vietnamese army later put down this rebellion near Kampong Cham.

Discussing such incidents with his privy council, Minh Mang said

“Thổ people [Cambodians] are incontrollable: at times they submit; at times they rebel, they are unpredictable. Last year, they endured several sackings and massacres by Siamese troops. Their land was bare. [I] look after them; the court dispatched an army to repel the enemy, saved them from despair and issued them blankets. Why then did they become hostile and turn into enemies of the Kinh [Vietnamese], and carry out massacres?“

When the new Thai king Rama III took the throne soon after, he was already concerned about Vietnamese expansion into Laos, which, with a large population of Tai peoples had long been considered under the influence of Siam.

This conflict, known as Anouvong’s Rebellion or Lao–Siamese War of 1826–1828 saw another direct confrontation between Siam and Vietnam. The city of Vientienne was razed to the ground by the Siamese in 1827. According to some sources after Minh Mang sent an envoy of one hundred men to learn of Siamese intentions, the answer was returned by a single man who had been left alive to deliver the message.

It should be noted that the Laotian kingdoms, also sandwiched in between Siam and Vietnam, suffered centuries of subjugation between the two powers.

An idea into the Vietnamese mindset comes from Hoàng Kim Hoán, vice-minister of the Ministry of Personnel, after Bangkok annexed Vientiane in 1827:

“Recently, after Siam invaded Lanxang [Vientiane kingdom], some court officials proposed that we should ignore Lanxang’s predicament and wait until Siam transgresses our boundary to strike back. I personally consider that Nghệ An is the backbone of our kingdom; beyond is Trà Lân, which borders Lanxang. Thus, Lanxang is our shield; it should not be abandoned. If the Siamese are waging this campaign [merely] to assuage their anger by looting property and kidnapping women, then there is nothing to be said. However, if they conquer garrisons and towns and oppress the people of Lanxang, it will be tantamount to destroying our shield. Even though they do not expand into our barbarian vassals’ lands, our vassal barbarians will be close to them [Siamese], and naturally will become their dependents. If our barbarian vassals become their servants, unavoidably Trà Lân, which now belongs to us, will be lost to them.“

Rama III, however, swore to put an end to what he described as ‘Vietnamese insolence and contempt’. Around this time some of the Cambodian elite who were being purged by the Vietnamese began fleeing to the north and west under nominal control of Siam.

Vietnam Rebellion, Siamese Invasion (1833-34)

It was not just the Khmer who were growing dissatisfied with Emperor Minh Mang. The southern portion of his country had been long settled by Chinese immigrants, along with Chams, ethnic Khmers and other Asian traders. The ancient kingdom of Champa, reduced over the centuries to a mere rump state was finally annexed by the emperor in 1832, sending more refugees westward.

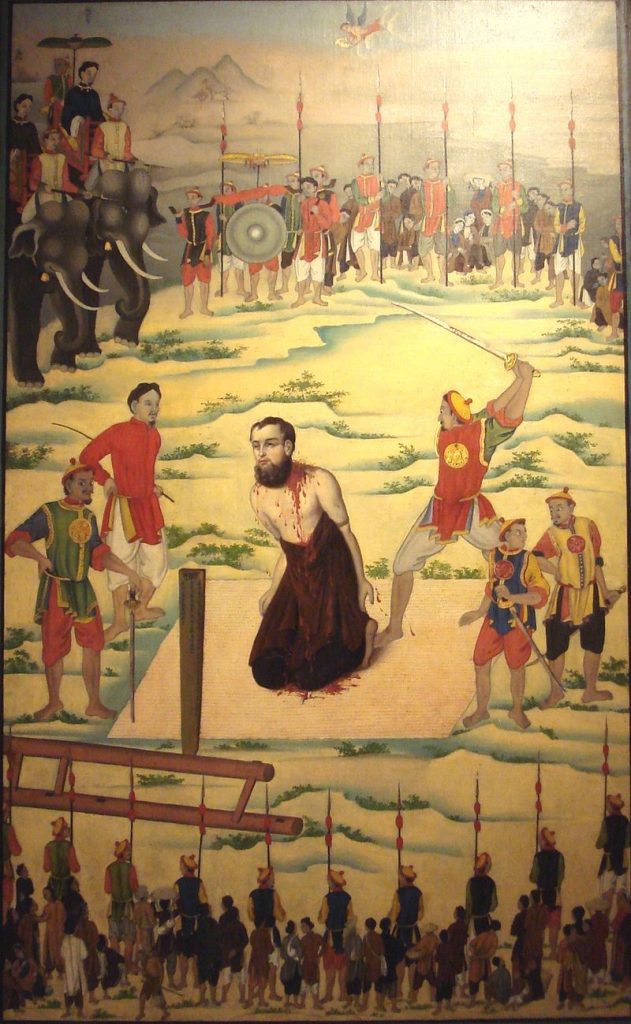

After the past intervention by the French, requested by Gia Long, the Emperor’s father, Catholicism had begun to take root in the region. Ming Mang was deeply suspicious of Europeans and especially Catholic missionaries, whom he banned from entering the country in 1825.

Between 1833 and 1838, at least seven French missionaries were sentenced to death and suffered cruel tortures, with Pierre Borie, Joseph Marchand and Jean-Charles Cornay later becoming canonized as saints in the 20th century.

In 1833 the Lê Văn Khôi revolt in southern Vietnam gave Rama III an opportunity. Led by the general of the same name who had escaped imprisonment under Minh Mang, and whose father, loyal to the previous emperor, had had his grave desecrated, the rebellion drew popular support from the catholic Vietnamese, French missionaries, Muslim Cham and the descendants of Chinese immigrants.

The rebels quickly took the Citadel of Saigon, and sent out a request for support from Rama III. The Siamese king sent his best general, Chaophraya Bodin (who had fought the Vietnamese in Laos) with a 15,000 strong army in November 1833, aiming to seize Phnom Penh and proceed to Saigon. The Siamese won a major battle at Kampong Chhnang and proceeded towards the city. Ang Chan and the outnumbered Vietnamese abandoned Phnom Penh, and Bodin advanced further into the delta, capturing the regions of Châu Đốc and Vĩnh Long. In February 1834 the Siamese force, now with overstretched supply lines were finally repelled, and as they retreated, torched towns and villages on the way back to Bangkok.

Ang Chan, returning with the Vietnamese army, died aboard the royal barge at Phnom Penh within sight of his burnt-out palace.

In 1834, the governor of Hà Tiên submitted a proposal to extend military campaigns beyond the Khmer land into Siam, Minh Mang replied:

“If we bring an army from far away to invade, can we be assured of victory? Even if we win, can we settle in their land? Can we command their people? Even if we could settle in their land and command their people, could we be sure that order would prevail over one hundred years? Therefore, is there any reason for sending soldiers to this far-flung boundary?”

The flat plains of central Cambodia, along with the Delta, could be consolidated by the Vietnamese, just as the east could be by Siam. Neither wished to extend far beyond what they thought they could hold and control. Yet both wanted control of the Mekong. The Vietnamese resettlement was continued bit by bit, described “Like silkworms eating mulberry leaves”

A Divided Land (1834-41)

Yet again there was no clear successor to the throne, and, in somewhat of a tradition, both Siam and Vietnam rushed to throw in their own candidates.

Ang Chan had two brothers, Ang Im and Ang Duong who set about their claims, while Minh Mang looked to the previous king’s daughters, as he had left no male heir. The Vietnamese had also taken the Khmer royal regalia, without which a coronation could not be legitimized.

The eldest daughter was seen as too pro-Siamese, so her younger daughter was crowned as Queen Ang Mei in 1834. The sisters were put under the ‘protection’ of Vietnamese bodyguards (100 for the queen, 30 for each sister), and the country was in reality ruled by her viceroy, Truong Minh Giang.

The viceroy was quoted by his emperor

“Trương Minh Giảng often told me that the Khmers are mostly simple and trustworthy, perhaps better than the Thổ people in the north. I don’t believe so. Among the Thổ people in the north, some are literate and fluent in the Viet language, and therefore can be educated. The Khmer are as thick as balls of mud and know nothing. Most of them, moreover, are cunning and deceitful. Even if one tries to pour advice into their ears and teach them, it cannot be done. I predicted what happens today. Luckily our country is now prosperous. [If] we lack soldiers, we can recruit more; [if] we lack grain, we can provide more. There will be a hard campaign before we can bring order [to the Khmer]. This great task should take place in my reign rather than be left for my sons and grandsons.”

Ang Im and Ang Duong had set themselves up as governors in the Siamese administered provinces, and a Siamese army began to mass on the western border.

The Vietnamese engaged in a ‘modernizing’ program, with court officials required to dress in Vietnamese costume every morning to deliver reports and receive their daily instructions, while civil administration was reorganized along Vietnamese lines. The country was divided into districts each administered by a Vietnamese military official seconded by a Cambodian oknha. The Cambodian army was modernized and placed under Vietnamese control, and strengthened with one Vietnamese soldier to every four Khmers, while masses of Cambodians were drafted into labor gangs to work on public projects.

Minh Mang declared after the 1834 invasion

“Chân Lạp [Chenla/Cambodia] is now incorporated in the map of Vietnam. I therefore want to reorganize it into prefectures and districts and to teach its people. However, its customs are different; to pacify people and seek their submission, we cannot rely on laws and rules alone. Only by introducing governmental institutions and gradually inserting them [into local society], can their old manners be changed.“

In 1840, the elder sister of Ang Mei, Princess Baen, was discovered corresponding with her mother and uncle who were living in Battambang and planning to escape to them. A rebellion broke out around Prey Veng and Ba Phnom. Baen was imprisoned and Minh Mạng, demoted Mey and the other princesses. In August 1841 they were all arrested and deported to Vietnam along with the royal regalia. Baen was later executed for treason.

War Returns (1841-45)

Minh Mang died January of the same year, and in April Ang Duong marched with a Siamese army, which quickly took control of Oudong and Phnom Penh. The Siamese launched another offensive in February 1843, Chaophraya Bodin, was charged with the capture of Saigon.

After initial success, by May a Vietnamese counter-offensive pushed back the Siamese, recapturing Cô Tô and taking a large number of prisoners.

In Cambodia, the Siamese forces began repeating some of the mistakes made by the Vietnamese, and soon lost the goodwill of the Khmer people through a heavy-handed occupation.

Some Cambodians then defected to the Vietnamese, and in July 1845, the Vietnamese crossed back into Cambodia with a force of around 20,000 men, advancing north toward Phnom Penh, capturing the city on September 13.

Bodin and Ang Duong retreated to Oudong, which was surrounded and besieged.

Rama III, writing of the situation in the 1840’s described how

“The Cambodians always fight among themselves in the matter of succession. The losers in these fights go off to ask for help from a neighboring state; the winner must then ask for forces from the other.”

Success of Ang Duoung (1846-60)

Peace negotiations began early in 1846 and a treaty was signed in 1847. It was agreed that all foreign troops should withdraw from Cambodian territory. Siam retained Battambang, Siem Reap and the northern provinces as far as the Mekong River, and Vietnam gave up Kampot.

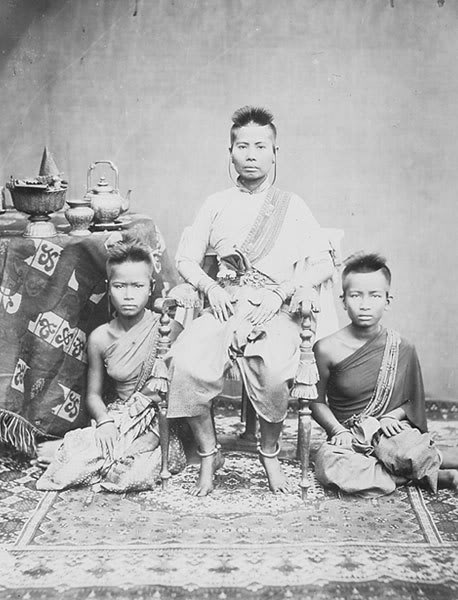

Ang Duong and Ang Mei were to be joint monarchs, sending tribute every year to Bangkok and every three years to Hue. Simultaneous coronations were held in Udong and Hue in April 1848.

The king remained close to Rama, consulting him on most major issues, while ‘Queen’ Ang Mei faded into madness and obscurity.

While Vietnamese politics began another period of internal strife, the peace in Cambodian lands drew peasants from the north into the delta area, displacing local Khmers, who in turn started migrating westwards across what was an ill-defined border into Ang Duong’s kingdom. The Vietnamese also encouraged, or coerced, criminals, the landless and ethnic minorities to settle on and around the frontier.

Faced with insurmountable issues from Bangkok and the Delta, Ang Duong turned to consolidate what he had left, and began a national programme of what could probably be described as ‘revisionist Khmerism’. Monasteries were built or renovated with monks trained to teach schoolchildren, the royal court was reinstated with a more traditional protocol, and the connection between king and his people became strengthened using occasions such as Royal Ploughing Festival and the Water Festival.

Himself a poet, Ang Duong also oversaw a period of Khmer literature and the arts, and is credited with authoring the code of conduct for women known as the chbab srey.

This code, written in the form of a poem gives advice to young girls such as:

“Don’t bring the outside flame into the house and then burn it.

Your skirt must not rustle while you walk.

You must be patient and eat only after the men in your family have finished.

You must serve and respect your husband at all times and above all else.

You can’t touch your husband’s head without first bowing in respect.

School is more useful for boys than girls.

Be respectful towards your husband.

Serve him well and keep the flame of the relationship alive.

Otherwise, it will burn you.

Do not bring external problems into the home.

Do not take internal problems out of the home,”

In all reality Ang Duong’s kingdom was near bankrupt. Wars, famine and mass deportations had decimated the economy and agricultural production. He oversaw the reduction of taxes and introduced the first coinage. In an effort to bypass Vietnamese tariffs levied on trade using the Mekong, labor gangs were used to construct a road from Kampot (at the time the only sea port). The route roughly follows modern day National Road 41/51 between Kampot and Udong) and was known as Ang Duong Road.

The French (1856)

The mid-19th century saw a rise in European colonization. The British had moved into Burma from India and were bordering southern Siamese states in British controlled Malaya. French forces were encroaching on Southern Vietnam, and for a while it may have been possible for Siam to fully annex Cambodia. Rama IV (King Mongkut, of ‘The King & I’ fame) managed to retain Siamese independence through a series of treaties and an open-mind to western thought.

Fortune of geography also helped the Siamese, as the kingdom shared no border with China (the back-door that both British and French interests were keen to exploit) and so became a buffer-zone between the two European powers.

Yet, unknown to Rama, Ang Duong had already sent letters to the Napoleon III. The contents of the first correspondence are unknown, as the documents have been lost.

In 1856 French diplomat Charles de Montigny visited Hue and Bangkok, where Rama learned of Ang Duong’s attempt to contact Napoleon. He then arrived at Kampot, where he expected to be received by the king, but was met by Siamese officials who prevented him traveling north. After been kept waiting for a week, after Ang Duong apparently suffered from ‘an attack of boils’, de Montigny was finally taken to Oudong.

There, the diplomat met with the prime minister and de Montigny presented a draft trade agreement, given the French exclusive access, while missionaries would have the right to build churches ‘in any place’. He returned to Kampot, and was reported to have been greatly surprised when he received word that Ang Duong had refused to sign.

The King Without Crown

Ang Duong died in 1860, leaving his eldest son Prince Norodom as his designated heir, which was also approved by Rama IV in Bangkok. Norodom, along with his half-brother Sisowath, was educated in Bangkok, and grew up alongside members of the Siamese royal court. However, the Siamese refused to release the sacred royal sword and seal, now in Bangkok, which were needed to legitimize a coronation, and denied the Vietnamese the right to also crown him.

There was yet another rebellion shortly after the death of Ang Duong when Norodom’s younger half-brother Si Votha began an uprising in the east. Although Norodom had served in the Royal Siamese Army, he proved inept as a military leader and the rebels took Phnom Penh, forcing Norodom to flee to Battambang and later Bangkok. He left his half-brother Sisowath in charge of the defense of Oudong.

At the end of 1862 Norodom returned with a Siamese army and the rebellion was put down. By this time the French had taken a foothold in Vietnam, with the Treaty of Saigon signed in June 1862. Under the terms of the agreement, the French received Saigon and three of the southern provinces of Cochinchina, the opening of three ports to trade, freedom of missionary activity, a vague protectorate over Vietnam’s foreign relations, and a large cash indemnity.

The French, still hoping for a route to China via the Mekong and wary of British and American influence on Siam, began reasserting old claims of suzerainty over Cambodia on behalf of their new colony.

Once again, a king of Cambodia was pressured from both sides of his borders.

First to move were the French, who, in mid-1863, sent Admiral Pierre Paul Marie Benoit de La Grandière, along with a gunboat, up the river to offer Norodom French ‘protection’ in return for navigation rights and control over foreign relations. La Grandière then visited Siem Reap and the ruins of Angkor Wat, still Siamese territory, but which he treated as if it were part of Cambodia.

Before the agreement was ratified in Paris, Norodom signed a clandestine treaty with Siam. It made Norodom the viceroy of Siam and governor of Cambodia; Siam retained control of Battambang and Siem Reap. In return he would finally be crowned and made Viceroy of Siam and Governor of Cambodia.

Norodom headed for Bangkok via Kampot in March 1864. Along the route a messenger caught up with his entourage and informed the king that French marines had seized the royal palace and gunboats were firing salutes to the tricolor flag. The French case was polite, but firm: if Norodom was leave Cambodia, he would never be permitted to return. The king-in-name turned around and headed back up Ang Duong’s road to Oudong.

The French moved to stop Siam from asserting further claims over Cambodia and forced Siam to return the royal regalia. Norodom was finally crowned at Oudong in June 1864, in the presence of both French and Siamese officials. He was installed as king in the new royal capital of Phnom Penh in 1866, and in 1867 Siam officially acknowledged the French protectorate over Cambodia.

One thought on “History: Between The Elephant And The Dragon, Part 2”