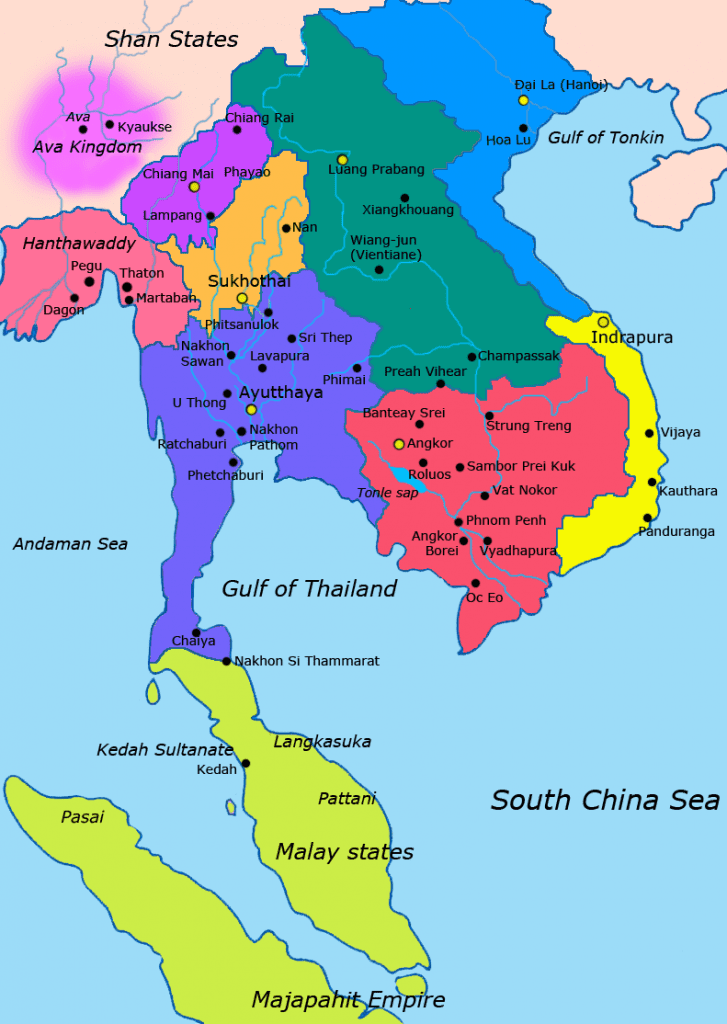

As great powers fall, others shall rise in their place. The Khmer empire, at its peak controlled or had under vassal, much of mainland Southeast Asia, from southern China to the Isthmus of Kra. Overstretched military campaigns, climate change, poor economic planning and ethnic rebellions all began to erode the once mighty kingdom of Angkor. Internecine fighting between powerful, and usually related, clans weakened the state, as neighboring kingdoms began to centralize.

By the fate of geography and politics, Cambodia found herself trapped between two aggressive and ambitious neighbors to the west and east.

The following is the first in the series on the relationship with the Thais to the West, Viets to the east, with Cambodia, relegated to a pawn on the board, stuck in the middle. Note that sources can vary, in both names, dates and versions of events. This piece has been sourced from various places, and there may be some mistakes.

The End of Angkor

The 13th and 14th centuries saw great changes to the political and social order of mainland Southeast Asia.

The area known as Sukhothai, which had rebelled and fought against the Khmer empire in the past was now coming under the dominance of a new Thai kingdom of Ayutthaya.

Amid this, the powerful Khmer kingdom was in a rapid decline.

In 1220, a Dai-Viet and Cham alliance had forced the Khmer to withdraw from many of the northern territories they had seized from Champa, while around the same time in the west there were Siamese rebellions, leading to the formation of the state of Sukhothai, widely considered by many to be the origins of the modern Thai nation.

At the end of the century, around August 1296, the Chinese chronicler Zhou Daguan arrived in the court of Angkor and described a kingdom, although still retaining pomp and ceremony, ravished by a long war with the Siamese.

He wrote of a cosmopolitan city with Chinese traders and a large number of Siamese, who were already becoming intermingled with the Mon-Khmer. Chams, ‘Yuvana’ (Vietnamese from Dai Viet in the Red River valley of far northern Vietnam), Pukom (Burmese from Bagan), and Rban, who have not been identified, are also recorded as having a presence.

There had been at least one devastating Siamese invasion in or around 1432 had lost much territory to the west, and appears to have had a major effect on the fighting ability of the empire.

According to Zhou, the once mighty Angkorian army as depicted on the walls of The Bayon, now had soldiers who stood naked and barefooted, armed only with lances and shields, and had no bows, armour or helmets, let alone trebuchets. ‘When the Siamese attacked all the ordinary people were ordered out to do battle, often with no good strategy or preparation.’

One theory is that over the 13th and 14th centuries, the Siamese and Khmers elites merged, with intermarriage among the elites creating a new class of mixed nobility, who were able to shift allegiances between rulers and challengers on both sides of the shifting borders, but still able to claim a link to the kings of Angkor. Perhaps some comparisons could be made to the complicated system of principalities, duchies and fiefdoms that existed in western Europe around the same period.

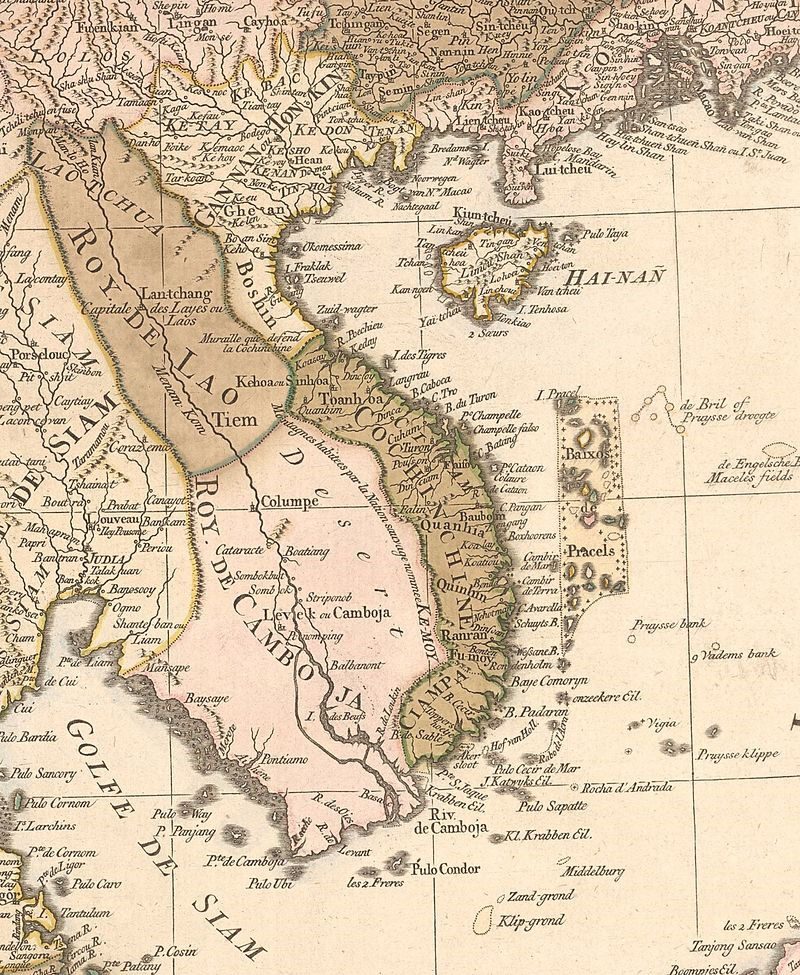

It should be noted that the Southeast Asian model of political control was not necessarily based on nationality, but a complicated model of family ties and patronage known as the ‘mandala system’. For example, Bassac, the most important town in the delta in the 1760’s (modern day Soc Trang), was shared four ways by a local warlord, the Nguyen, the King of Cambodia and the King of Siam, with none able to exert total control. Provincial governors could, and would, be bribed, coerced or killed in order to change allegiance.

Certainly, bonds of blood existed between the Khmer and Siamese, as did the common religion of Theravadin Buddhism. Opportunist princes and nobles would easily have been able to switch loyalties and call on family roots that extended from Ayutthaya, Sukhothai and Angkor.

By 1431 or 1432 Angkor was abandoned for reasons which, although well debated, have never been conclusively understood. Sources for the so called ‘Dark Ages’ of Cambodia are mixed with legends and are often contradictory, but it is a certainty that the Siamese, or indeed an elite of Siamese- Khmer ancestry, often meddled militarily in the affairs of Khmer politics.

Take, for example, the legend of Sdach Khan, a commoner whose beautiful sister became a wife of an unjust king called Sugandhapad. Khan later killed the king and took the throne, and, the stories go, was a wise and competent ruler. However, his usurper’s reign was cut short when the late king’s brother returned with a Siamese army and Sdach Khan was defeated and executed.

The Dragon Rises

Around the same time that Angkor was abandoned, Vietnamese resistance to the so-called ‘Fourth Chinese Domination’ period (1407-1427) saw the Ming dynasty leave Dai-Viet. Vietnamese folk hero Lê Lợi, founder of the Lê dynasty took on a kingdom that, although independent, was still a vassal state of the Chinese. Under Ming rule Viet males were conscripted into military service, and Chinese technology, including the use of gunpowder, were passed down to the new lords.

In the same way that is presumed the Siamese and Khmers forged allegiances, the Chinese and Vietnamese nobility also married off their sons and daughters in political wedlock.

The Mongol conquest of China at the end of the 13th century had pushed many groups, most notably the Tai people, who settled around Khmer lands on the northern parts of the lower Mekong (modern day Laos) and down into Ayutthaya and Sukhothai where they mixed with Tai people who had migrated over the centuries.

By 1471, Le troops led by king Lê Thánh Tông invaded had invaded Champa and taken the capital of Vijaya, effectively ending the ancient kingdom as a serious regional power. The Khmer armies refused to help their old ally/enemy, with whom they had previously fought the Viets alongside. This may have been for political reasons after Champa after the Chams switched sides in a war against Dai-Viet in the previous century, or could be that the Khmers were not in a position of strength to intervene.

The Viets also spread westwards into the kingdom of Lan Xang (modern day Laos), which had long been in the sphere of influence of the Angkorian empire through marriages and tributes. The ‘White Elephant’ war of 1479-1480 was supposedly started, in part at least, after the ruler of Lan Xang sent emperor Lê Thánh Tông a chest full of dung, excreted by his famed white elephant. The result of this war ended much as it had started, with Viet troops withdrawing back to their borders after threats from the Chinese, to whom Lan Xang had a vassal status.

Constrained by the Chinese in the north and Lan Xan to the west, Viet raids on the Mekong Delta region began.

A new threat from the west had emerged for the Siamese in the form of the Toungoo dynasty from Burma. A resurgent Khmer army marched on Ayutthaya, but were eventually beaten all the way back to the post-Angkor capital of Longvek and were soundly defeated by the Siamese forces. In 1594 Longvek finally fell and a puppet monarch was installed.

Read about Spanish and Portuguese actions at this time here

For the next few decades the court at Ayutthaya became kingmaker, intervening when necessary to make sure they had a loyal king on the throne.

At the end of the 16th century a civil war broke out among the Viets, with the southern half of the country falling under control of the Ngyuen lords in the central and southern lands of Đàng Trong, while the Trinh dynasty held the northern portion of Đàng Ngoài, which would later become known as Cochinchina and Tonkin.

An at-the-time standard marriage of alliance was sealed between the illegitimate daughter of southern lord Nguyen Phuoc Nguyen and King Chettha of the Khmer sometime around 1618.

The alliance was of benefit to both sides, Khmer help, especially with the provision of war elephants, was used to shore up the defensive line between north and south, while Viet manpower was promised in the west to halt further Siamese expansion. Two invasions from Ayutthaya were successfully repelled in 1622 and the following year.

Vietnamese were given permission to settle around the Mekong Delta region in the area of Prey Nokor, referred to in Viet as Sài Gòn. In 1623 a customs house to collect taxes for the Ngyuen lords was permitted to be built in Prey Nokor, giving further legitimacy to civilians moving south to flee the civil war and settle in the Mekong Delta.

The 17th century was the beginning of the age of commerce. The Dutch East India Company was active in Ayutthaya as well as Hoi An under control of the Ngyuen. The Portuguese and Spanish had long been in the region, and the British were arriving in the name of trade.

In 1642, with the support of the Malays and Chams, the third son King Chettha murdered his brothers Padumaraja and Outhei. First reigning as a Buddhist king under the name Ramadhipati, he later converted to Islam, sought help from Chams and Malays, and adopted the title Sultan Ibrahim.

Following a war with the Dutch (read HERE), in which the European power were humiliated, two sons of Outhei launched a revolt, appealing to Nguyen Hien Vuong, the king of Hue, for military support.

The Vietnamese invaded and fought against the Sultan and his Cham and Malay allies. Ibrahim was defeated and taken to Hue in a cage, where he died in captivity in 1659. Following death, he was given a Buddhist funeral, whether through his own wishes, or as a final insult is not clear.

The Vietnamese again intervened from 1673–1679, and the final decades of the 17th century descended into a series of assassinations and coups.

To the west the Siamese spent much of the 17th century at war with the Burmese, with conflicts from 1593-1600, again between 1609-22 and 1662-64.

Delta Issues

The fall of the Ming dynasty in China in 1680 by the Manchus sent a flood of Chinese refugees south into both Vietnamese and Khmer lands. Those who arrived at Hue were encouraged to settle in the Mekong Delta, in the newly created Viet provinces of Bien Hoa and Gia Dinh. The relatively insignificant town of Prey Nokor/Saigon was now firmly under Viet control.

Cambodia in the Middle

The Siamese and Vietnamese began to clash over Cambodia at the beginning of the 18th century. Ang Tham (also known as Thommo Reachea III) ascended to the throne in 1702. With the help of Thai Sa, king of Ayutthaya, Ang Tham forced his rival and vice-monarch (the Uparat) Ang Em (also known as Barom Reameathiptei) to flee to Saigon in 1705, where he was given refuge in the court of Nguyễn Phúc Chu.

A Vietnamese army supported Ang Em/Barom Reameathiptei, who then seized the throne around 1710-15, this time sending Ang Tham/Thommo Reachea III into exile in Ayutthaya.

Around 1717 the Siamese attacked again, but a large fleet suffered a heavy defeat by the Vietnamese at Banteay Meas (in modern day Kampot province). However a land invasion force reached the capital at Oudong in 1718 and eliminated Vietnamese troops in the city. Ang Em/Barom Reameathiptei then agreed to pay tribute to the Siamese court as Ayutthaya’s vassal state in exchange for the Siamese’s acknowledgment of him as the legitimate king of Cambodia.

The crisis seemed averted, at least temporarily, and in 1722 Ang Em/Barom Reameathiptei, abdicated the throne in favor of his son Satha II (also known as Barom Reachea X and Ang Chee).

Ang Tham/Thommo Reachea III returned to Cambodia in 1736 with the Siamese, deposing Satha II, who took up a now familiar pattern of escaping to Saigon to plot revenge.

A series of assassinations and coups followed the death of Thommo Reachea III in 1747, with Satha II returning from exile to briefly retake the throne with the aid of a Nguyen army in 1749.

While the Cambodian court descended into bloody coups and palace intrigue, by 1700, some 40,000 immigrants had settled in the Mekong Delta. Prior to drainage canals and land reclamation, this swampy marsh, prone to flooding and tides had little in the way of ‘good’ land, increasing tensions between the newcomers and the Khmer who had lived in the region for centuries.

In 1731 there was an uprising in the important port of Ha Tien, led by an ex-monk and supported by Khmer officials. This spread across the delta, with a French missionary in the area reporting that Khmers ‘killed all those (Vietnamese) that they found in Cambodia, men, women and children’. The Nguyen blamed the Cambodian king and launched two attacks, which were mostly repelled, with the Khmers retaining control of most of the region.

There were two more recorded cases of mass-slaughter against Vietnamese in 1749 and 1769.

Over in Ayutthaya, the Burmese–Siamese War (1765–1767), known to the Thais as the “war of the second fall of Ayutthaya”, saw the sacking of the capital and the downfall of the Ban Phlu Luang dynasty. After a 14-month long siege, the city of Ayutthaya was finally razed to the ground. Following the destruction, Burmese forces remained for a few months, before redeploying to fight off a Chinese invasion.

A New Siam

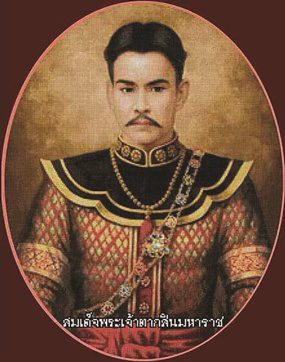

In the chaos that ensued, one of modern Thailand’s first great heroes, Taksin ‘the Great’, managed to reunite the warring Siamese factions, and again took the Thais back into meddling with Cambodian affairs of state, coming up against the Nguyen lords in the process.

This chapter began in 1758, when Ang Ton seized the Cambodian throne to rule under the name of Outey II. To cement his legitimacy, he had purged much of the royal family, yet his cousin, known as Ang Ton II, managed to escape and took refuge across the border in Ayutthaya.

A decade later, with Taksin firmly in control in the new Siamese capital of Thonburi, he decided to seek recognition and tributes from the Khmer king. Outey II, who was still on the throne, refused to bow to the new Siamese ruler, and insulted him. Taksin attacked Cambodia in 1769 with the intention replacing Outey II with his cousin, and bitter rival Ang Non II, and thus bring back Thai influence, but the campaign was a failure.

In 1770, Taksin followed his unsuccessful incursion with a direct attack against the Vietnamese, following their support for, and occupation of Cambodia.

The Vietnamese believed this attack was designed to take out potential rivals to Taksin, such as Prince Sisang, son of Thammathibet, the former Viceroy of Ayutthaya (and grandson of King Borommakot, one of the last monarchs of the kingdom) who had taken refuge in Cambodia, and Prince Chui (son of Prince Aphai, grandson of Thai Sa) who had fled to the port of Hà Tiên where he was sheltered by Mạc Thiên Tứ, the governor of the principality.

A back-and-forth proxy war between Siam and Vietnam continued actively through 1771 and the Siamese seized the port of Ha Tien.

For much of this time the weakened Cambodian state had two monarchs, who looked both east and west for support, and were used and disposed of as necessary.

Taksin faced troubles at home, and withdrew most of his forces, while at the same time the Tay Son rebellion began, ending the rule of the Nguyen lords and later provoking more conflict with the Siamese, with many of the Vietnamese elite seeking refuge in Siam. Cambodia now shifted into ever-increasing lawlessness, with governors rebelling, taxes remaining unpaid and outbreaks of diseases such as cholera and starvation rife among the population.

A coup deposed Taksin, and on April 10, 1782, the great unifier of the Thai people was executed (with some sources claiming a plot between Thai and Vietnamese generals leading to his downfall). Taking his place was the founder of the Chakri dynasty and ancestor to the current Thai royal family Thongduang, better known as Rama I. Himself descended from a Mon lineage, Rama raised (which should probably be read as kidnapped) a young Cambodian prince named Ang Eng as his own son.

Rama I sided with the deposed Nguyen lords against the new Tay Son leadership. In 1784–1785, the last of the Nguyễn Lords, Nguyễn Ánh, convinced Rama I to give him forces to attack Vietnam, but the joint Nguyễn-Siam fleet was destroyed in the Battle of Rach Gam–Xoai Mut in the Mekong Delta. Over 40,000 Siamese troops were killed in the battle.

Ang Non II, a Siamese puppet king who ruled from 1774-79, led Khmer forces against the Tay Son. He reconquered several Vietnam-controlled provinces such as My Tho and Vinh Long back to Cambodia, but was kidnapped by Vietnamese agents and drowned.

The young Ang Eng, who had been raised in the Siamese court, now aged around 20, was installed as king of Cambodia with the help of Rama I, and named Neareay Reachea III. As part of the arrangement, and to avoid yet another civil war, the provinces of Battambang and Siem Reap were ceded to a Siamese friendly ‘Lord Governor’, effectively making them a proxy state of Siam.

Ang Eng died on trip to Bangkok less than two years later, and his eldest of 4 (or 5 sons), Ang Chan (reigned as Outey Reachea III), who was just 5 years old was named his successor. However, he was not permitted to leave Siam for his kingdom until around 1806 after the death of a Cambodian lord, who had been acting as regent for the Siamese.

Ang Chan was not enamored towards his mentors/captors and quickly looked to the Vietnamese.

A United Vietnam

In the east, one of the few surviving Nguyễn lords, Nguyễn Ánh, had finally beaten the Tay Son by 1802 and crowned himself emperor Gia Long. A unified Dai-Viet, renamed Vietnam, now stretched from the Chinese border down to the Gulf of Siam.

The new emperor had received assistance from the French, via a Catholic priest named Pigneau de Behaine, beginning the French adventure in Indochina.

Ang Chan II, like so many of his predecessors, had family troubles. In this case his brothers Ang Em and Ang Snguon, were pro-Siamese, and a threat to his rule. He started to pay tribute to Vietnam, who granted him the title Cao Miên quốc vương (“king of Cambodia”).

He then rejected Siamese demands to appoint Ang Snguon and Ang Em as the uprayorach (second king) and ouparach (viceroy), and in 1811, with the help of Siamese, Ang Snguon overthrew him. Ang Chan fled to Saigon. His two brothers were appointed regents by Siamese. In 1813, Ang Chan returned with a Vietnamese army under Lê Văn Duyệt and captured Oudong. Ang Em and Ang Snguon fled to Bangkok.

Eastern Cambodia was put under protection of Vietnam. The Vietnamese built two forts Nam Vang (Phnom Penh) and La Yêm (Lvea Aem), and around 1000 men under Nguyễn Văn Thoại were sent to Phnom Penh to “protect” the king, yet the Siamese still held on to much of the north and west.

As a compromise between the powers, it was agreed that King of Siam would be the ‘father’ and the Emperor of Vietnam as the ‘mother’ of Cambodia, splitting the kingdom into zones of influence.

Part Two (and possibly three) will (hopefully) look at the final rebellions against the Vietnamese, the arrival of the French, the Vietnam war and PRK relations between the three states.

Submitted by History Steve (special thanks to Philip Coggan, whose work An Illustrated History of Cambodia was lifted in small parts.)

One thought on “History: Between The Elephant And The Dragon, Part 1”