Thiounn Prasith was born in Phnom Penh on 3 February 1930, the youngest of five children from a conservative family working for the French colonial administration. He later served in the Khmer Rouge regime’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, survived the purges and went on to become the permanent UN ambassador for the exiled government following the Vietnamese led invasion of 1979.

Although the public face of the Khmer Rouge in the 1980’s and well known in diplomatic circles, Thiounn Prasith managed to fade into relative obscurity following his retirement. While others in his circle were subject to crime against humanity charges, ‘Pol Pot’s spin doctor’ and ‘the Khmer Rouge’s chief apologist’ managed to live comfortably in New York until 2001, and is now thought to reside in Paris.

He is an interesting subject, not the least as he has given two separate accounts of his life. The first was a ‘confessional autobiography’ in 1976, penned “Because the Comrade who is in charge gave the news that there is a class enemy accusing me, I’d like to write this biography for Angkar, honestly and from my heart”.

The second was given in 2009 by French police investigating crimes against humanity charges for the ECCC involving Kaing Guek Eav (Duch), Khieu Samphan, Ieng Sary and Ieng Thirith. (PDF HERE) In the latter, he told Maréchal des Logis-Chef Patrick Gerold of the French Gendarmerie that the 1976 story was made under duress to save his life.

Early Life

According to his accounts, Thiounn left for France in 1949, first to study dentistry and pharmacy before moving to the École Supérieure des Transports in Paris.

In Paris he was a member of a student group advocating Cambodian independence, and made the acquaintance of several Cambodian revolutionaries, including Ieng Sary, but later denied any knowledge of, or involvement with Communist Party activity in the city.

His 1976 ‘confession’ stated he was briefly detained by French police in 1953 for his left-wing student actions, but was released after a day.

In 1954 Thiounn married Christine Gouret, a French woman. The couple later had two daughters and a son.

Following an internship with French rail operator SNCF, he returned to Cambodia in late 1955 and became Deputy Manager of Operations at Royal Railways.

Communist Ties

David Chandler, in his book Brother Number One: A Political Biography of Pol Pot, claims Thiounn was one of 21 Cambodian Communists present at the secret 1960 meeting in Phnom Penh railway station, where the underground group was renamed The Khmer Workers’ Party. This meeting is considered to have been the founding point of The Khmer Rouge movement.

It has also been stated that Thiounn was the one who secured the use of the building for the meeting through his contacts. In interviews he has always denied this. “I was not aware of the CPK (Communist Party of Kampuchea); my work with the railways was all I had on my mind” he told Paris police.

Accused, he says, of being a ring-leader for agitation after he submitted a petition in support of a young engineer to the Director of Railways, he again left for Paris in 1963. He claimed the main reason for the move was to treat his glaucoma.

Back in France he worked for the capital air authority Aéroports de Paris. During this time, he bought property in Paris and fell in to the trappings of a capitalist lifestyle. His wife worked as a family planning counselor in Orly sub-district and, although he told ANGKAR she was a member of the French Communist Party, she had no real involvement. “She joined the French Party in 1970. But she did not agree with the French Party on many things. In general, she wants to gain benefits and wants to be comfortable. She is not a politician.”

The GRUNK Years

In 1970, following the Cambodian coup, he left for Beijing, to join deposed Prince Sihanouk’s GRUNK government in exile. He was soon made Minister of Coordination under former Prime Minister Penn Nouth, a Sihanouk loyalist who headed the ‘external’ section of the administration, and Khieu Samphan, the leftist politician who was in charge of the ‘internal’ section.

He described his role as one of a message conveyer between the sections ‘I was a postman of sorts’.

Although he later played down his position, he was described in a September 1970 interview with controversial journalist Wilfred Burchett as ‘A member of the government and Secretary of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the United National Front’.

For the first half of the 1970’s Thiounn was involved in international diplomacy, attending conferences and meeting with representatives of various foreign governments on behalf of the GRUNK.

Khmer Rouge Role

After the fall of Phnom Penh in 1975, Thiounn worked as a French and English translator for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs under Ieng Sary in ‘B1’, located near Ponchentong airport, and accompanied his boss on foreign delegations and meetings. He also became a regular face at the UN and made trips to sympathetic and non-aligned countries.

13 September 1979

Thiounn was denounced (he believed twice, once in a Toul Sleng confession of Toth Kham Duon, former ambassador to China) as both a CIA and KGB agent in 1976 and 1977. Under the guidance of Ieng Sary, he wrote his ‘autobiography’, which was published on December 25, 1976.

Unlike others in his workplace, he survived the allegations, although he French investigators that the regime had lost trust in him, and he was demoted to taking care of the ministry grounds and gardens. Through this manual labor, he was ‘re-educated’ and said the main reason he thought he had survived the purges was because the regime needed to keep some ‘intellectuals’ alive and active in order to function.

He also noted that the fact his grandfather was Veang Thiounn, First Minister under the French colonial authority, and his brothers held various top positions in the government, which may have had a part keeping him out of Toul Sleng. Thiounn Thioeun (died 2006) was the DK Minister of Health, and Thiounn Mumm (still thought to be alive, aged 94) a senior scientist at the Ministry of Industry, and former GRUNK Minister of Interior. Both had been close to Pol Pot since their student days in France.

The re-education over, Thiounn represented Democratic Kampuchea at the UN in New York in September 1977. He rebutted French concerns over human rights abuses under the regime, in a speech he later claimed was prepared for him by Ieng Sary.

Indeed, throughout all his tenure for the Democratic Kampuchea period, and following its overthrow, he strongly denied any knowledge of the mass atrocities carried out in its name.

In March 1980, when asked by Newsweek about reports that a million Cambodians had perished under Pol Pot’s rule, he said: “We estimate between 10,000 and 20,000 persons were killed, 80 per cent of them by Vietnamese agents who infiltrated our government.”

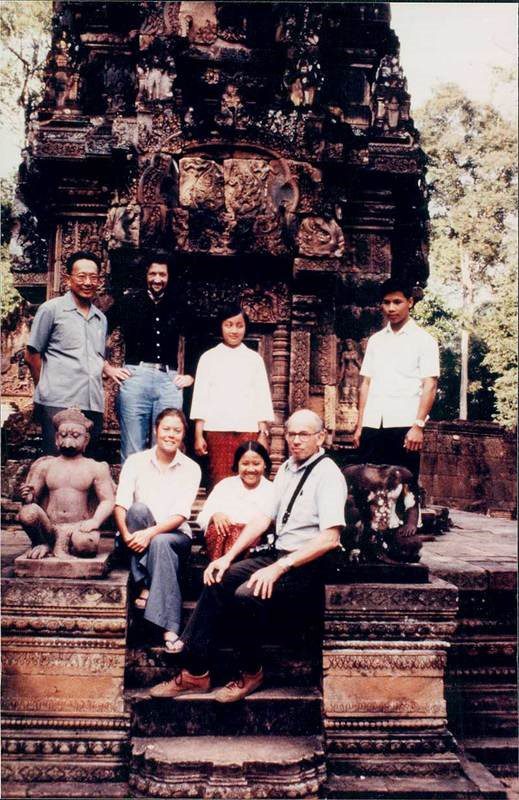

Once back in favor, Thiounn accompanied foreign visitors who had been permitted access. These show tours, mostly for friendly foreign dignitaries and, on one occasion, western left-wing journalists, were aimed at curbing some of the negative reports that were slowly trickling out of the country, and providing international propaganda for the Democratic Kampuchea regime.

He was present during the fateful trip of Elizabeth Becker, Richard Dudman and Malcom Caldwell of December 1978.

Dudman described his audience with Pol Pot in a 2015 article for the Post-Dispatch. “He spoke in a quiet monotone. He spoke in Cambodian, Foreign Minister Ieng Sary put the Cambodian into French, and another official (presumably Thiounn) translated into English.”

That same evening, December 23, Caldwell was shot dead in the guesthouse the group were staying with under guard. Elizabeth Becker, who was confronted by a gunman, but was not shot, later said the news of Caldwell’s death was broken to her personally by Thiounn Prasith.

Discussing the case in 2009, Thiounn said that he had been accused by some in the party as the one responsible for the killing, but no action was taken as, on December 25, a full-scale Vietnamese invasion was launched.

Another accusation against Thiounn from his time in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs involves the call for Cambodians living abroad to return to join the rebuilding of the nation. Out of around 1,700 who did so, only about 200 survived, according to Ong Thong Hoeung, an economics student who left France for Cambodia in 1976, who gave evidence at the Khmer Rouge tribunal in 2012. Many were sent to Boeung Trabek ‘re-education’ camp, a place Thiounn denies knowing existed.

Thiuonn insisted that he tried to dissuade intellectuals from returning during a telephone conversation with the New York Times in 1995, but refused to discuss politics or expand on his denials further.

The Ambassador in New York

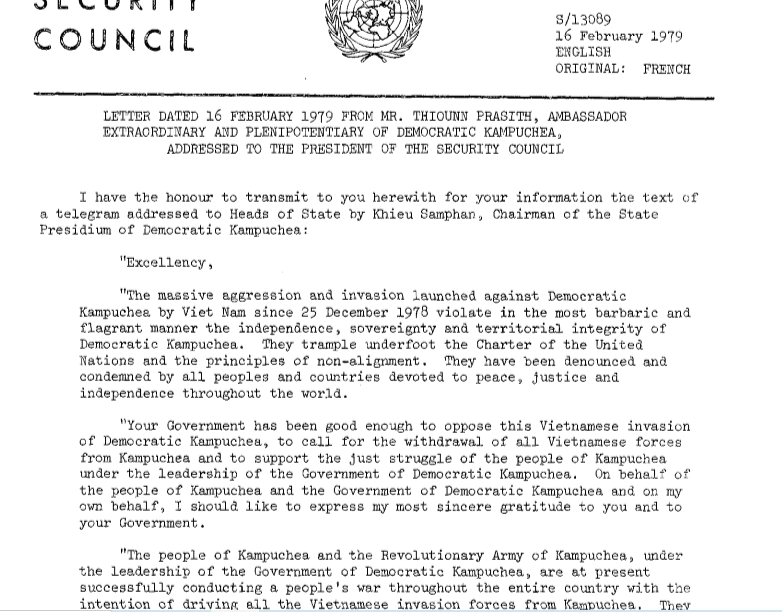

As soon as Democratic Kampuchea crumbled, Thiounn accompanied Sihanouk and Keat Chhoun to New York. He was soon writing to the President of the UN Security Council with the title ‘Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Democratic Kampuchea’, a title bestowed on him by Ieng Sary.

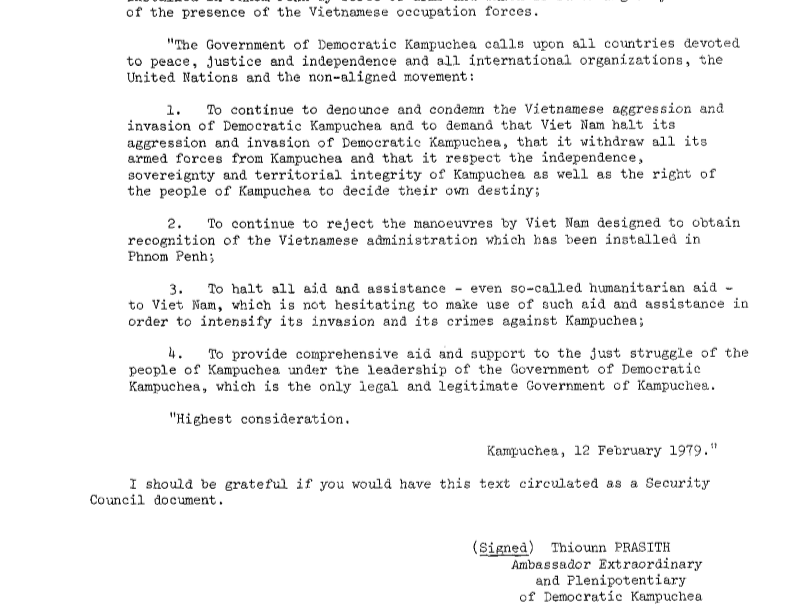

The United Nations proceeded to debate the situation in Cambodia in early 1979. Despite objections from Eastern Bloc countries (and Cuba), an alliance between China and the USA in the Credentials Committee of the 34th Assembly (1979) managed to sway the vote 6-3 in favor of allowing the Democratic Kampuchea government in exile to retain a seat at the UN. The Cuban ambassador decried the vote as an action ‘based on letters from a non-existent government which does not control a single inch of territory of Kampuchea’.

21 August 1979 (UN/ M Jimenez)

Thiounn Prasith was then accredited as permanent representative for Cambodia by Secretary General Kurt Waldheim. He would stay in this role until 1991, as he lobbied for the ‘total withdrawal of Vietnamese troops, the election of a new national assembly and an independent, peace, neutral and non-aligned Kampuchea’. From 1991-93 he became the deputy under a new power sharing agreement.

In 1982 the tripartite Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea was recognized internationally. The exiled alliance was made between Sihanouk’s FUNCINPEC, The Party of Democratic Kampuchea (still led by Pol Pot until 1985) and the right wing Khmer People’s National Liberation Front (KPNLF) under Son Sann.

Thiounn later said he wanted to step down as ambassador when the CGDK was recognized, but his resignation request was rejected by Sihanouk.

Thiounn Prasith’s last public international role was as a Khmer Rouge representative in talks in Jakarta in February 1989, between several Cambodian factions and representatives of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

After Politics

After ending such positions, standard protocol states that diplomatic passports be turned in and the former representative leaves the United States with 30 days. Thiounn continued to live in the New York area, first in Manhattan and later a stucco house on a quiet street in Mount Vernon. He told the New York Times by telephone that he was residing legally in the country.

In September 1995, after learning of Thiounn’s presence, the State Department declared it would try to find a way to expel him from the country.

In 2001 Thiounn moved to France, where it is believed he still lives. He turned 90 this year.

Submitted by History Steve for CNE

Other sources: New York Times, Village Voice, Phnom Penh Post, United Nations, Cambodian Documentation Center

One thought on “Thiounn Prasith- Pol Pot’s Spin Doctor”