This is Part Four of the series. Read PART ONE, PART TWO, PART THREE

The UN Arrives

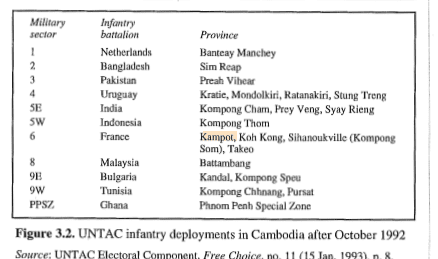

Following the Paris Peace Agreement, United Nations troops moved in quickly. The advance units of United Nations Advance Mission in Cambodia were organized in October 1991, and on 10 November 1991, 45 Australian Army personnel under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Russell Stuart, were among the first to arrive.

One of the first tasks was to provide communications equipment to the rival factions of the incumbent government (now named the State of Cambodia, under the also newly monikered Cambodian People’s Party), FUNCINPEC, KPNLF and the Khmer Rouge (NADK) to promote dialogue between leaders.

The Accords committed the four Cambodian factions to a ceasefire, an end to their acceptance of external military assistance, the cantonment and disarmament of their military forces, the demobilization of at least 70 per cent of such forces prior to the completion of electoral registration, demobilization of the remaining 30 per cent or their incorporation into a new national army immediately after the election, and the release of all prisoners of war and civilian political prisoners. Each faction would retain its own administration and territory pending the election and the formation of a new national government.

The Australians also help prepare a communications HQ for the main UNTAC force, which began officially on 15 March 1992. However, this lengthy wait for the main force to arrive led to outbreaks of fighting as all sides tried to consolidate their positions in preparation for the upcoming elections.

A motorbike transporting goods and people to Kampot. [August 1992], UN Photo/Pernaca Sudhakaran

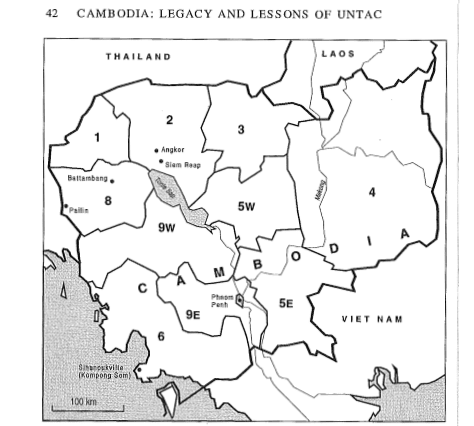

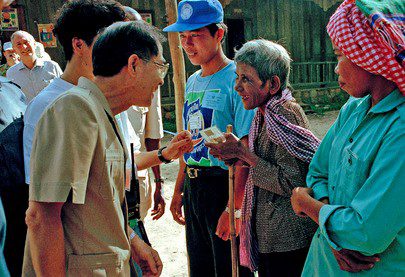

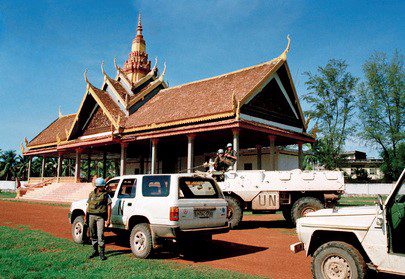

Armed forces, civilian police and a range of volunteers from 46 countries finally came to Cambodia to supposedly enforce an agreed ceasefire and prepare for free and fair elections scheduled for 23-28 May 1993. Kampot was placed within Sector 6, under French command.

Arguments over the effectiveness and value of the UNTAC mission (which cost the equivalent of $293 billion in today’s terms) are still being made. The elections, boycotted by the Khmer Rouge, were organized and mostly passed off successfully with a voter turnout of 89.56%. FUNCINPEC under Norodom Ranariddh won a majority 58 seats out of 120 with 45.5% of the vote, the KPNLF, renamed the Buddhist Liberal Democratic Party, came a distant third with 10 seats and 3.8%. Kampot province was won by FUNCINPEC. The political fallout was far from orthodox.

French soldiers serving with UNTAC providing security during Cambodia’s general elections for a national constituent assembly. The elections, scheduled for 23 – 28 May 1993, are being carried out under the supervision of UNTAC. 24 May 1993, John Isaac

From a military point of view, UNTAC did not succeed in fully ending the armed conflict that had raged for decades. The isolation of Cambodia since 1975 meant very little on the ground intelligence was available to the UN or the pre-Khmer Rouge Cambodians who had been living in exile. Meanwhile the Khmer Rouge and State of Cambodia (still thought as Vietnamese puppets by the KR) both distrusted the foreign intervention almost as much as they distrusted each other, one labeling it as youn-TAC and ‘a paper tiger’ respectively.

Khmer Rouge Threat To Peace

The Khmer Rouge controlled around 6% of the territory, including camps in Kampot and nearby Kampong Speu and Pursat. Many Thai border areas were also in KR hands, with the major bases of Pailin under General Nikon, and Anlong Veng, under former Southwestern Zone commander General Ta Mok.

Demobilization and disarming on the factions began in June, but the Khmer Rouge leadership refused to comply, claiming that Vietnamese were still inside the country preparing to attack. As UNTAC forces made efforts to reach KR areas, they faced roadblocks and sabotage routes. The other groups soon complained and the disarming of all sides was halted by September.

UNTAC was also suffered from weakness when it came to military intervention, and were embarrassed several times by not being able to protect civilians, especially Vietnamese. Seven were killed in Tuk Meas, east of Kampot town on July 21, 1992. According to a UN report, uniformed men armed with assault rifles and grenades fired at villagers from close range. One woman died and fell on her 7-day-old baby, crushing the child’s skull. Both government forces and the Khmer Rouge were blamed for the massacre, which they denied, although the Khmer Rouge radio station applauded the killings.

UNTAC departed in September 1993, leaving behind a newly restored monarchy and a curious government shared between FUNCINPEC and CPP. The new national army, the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces (RCAF) was dominated by former state soldiers and commanders, but FUNCINPEC and KPRAF units were incorporated. An increasingly isolated Khmer Rogue still clung on to what they still had.

Outside of the jungles, the UN intervention had led to an economic boom in the towns and cities. Aid and reconstruction cash flowed in, and international companies were drawn to the next ‘Asian Tiger’. This news was broadcast into the jungles on radio stations such as VoA.

What Were They Fighting For?

Beijing opened the first of the great sign of capitalism McDonalds in 1992, Moscow first saw the golden arches in 1990. There were even signs of a coming thaw in relations between the United States and Vietnam. Marx and Lenin were no longer en vogue, as Francis Fukuyama wrote (somewhat erroneously) in 1992 “What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such … That is, the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”

As part of the peace terms, China had stopped sending military aid and equipment to the Khmer Rouge. Tighter controls on timber and gem smuggling across the Thai border also reduced funds to the KR occupied areas of the northwest, although some former staunch communists are reported to have amassed extreme wealth by reinvesting profits into the Thai property market. The remaining fighters in the south were left facing shortages of food and ammunition.

Bandit Country

Banditry became a source of income for the Khmer Rouge, as well as still-armed former soldiers and poorly paid government troops. The Khmer Rouge received most of the attention and blame, but the routes to the coast were still dangerous to travel.

According to a 1995 HRW report: The practice of kidnap had become almost institutionalized in Kampot province as supplies from northwest Khmer Rouge bases dwindled during and after UNTAC. One resident of Kampot described hostage-taking as an everyday event, with ransom much like “taxes” calibrated to the victim’s means. In April 1994, the Khmer Rouge captured four very wealthy Cambodians, three of whom were generals (one of whom had just purchased his rank a few weeks before). In their case, they were each “priced” at over $10,000.

A more prosaic instance in April was the marriage of a working man in Kompong Trach district, who had to ensure that the wedding would not be disrupted by paying 10,000 riel ($5.00) to government officials as “tax” and delivering to the Khmer Rouge of his neighborhood three oxcarts of dried stingray and three gallons of rice wine.

The first Western attention on the Kampot situation came before Khmer New Year 1994, when Khmer Rouge abducted US national Melissa Himes, 24, in Kampot province on March 31. The American and three Cambodians working for Christian aid organization Food for the Hungry International in Chuuk.

Himes and her Cambodian colleagues were seized when they went to retrieve one of the aid group’s vehicles after a dispute about where the aid group would dig wells in the area, which was partially controlled by Khmer Rouge fighters. They were released unharmed 6 weeks later, following negotiations with US government representatives- the ransom paid was reportedly three tons of rice, 100 bags of cement, 100 sheets of aluminum roofing, medicine and 1,500 cans of fish. They also kept the car. The next westerners were not as fortunate.

Western Targets

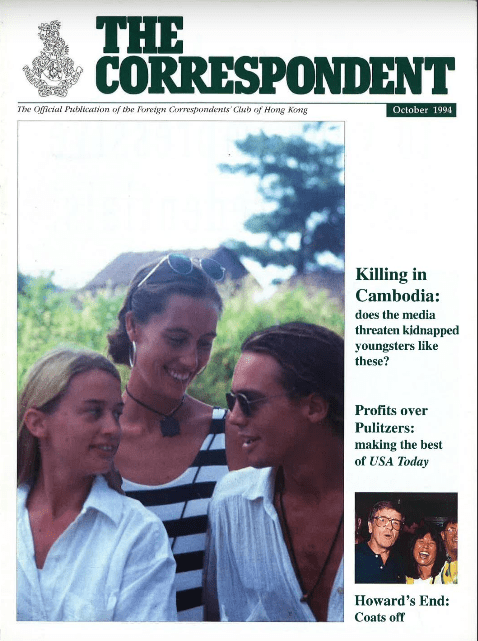

At 3.30 pm on 11 April, 1994, two young Britons and an Australian hired a taxi in Phnom Penh, for the hazardous drive to Sihanoukville. Dominic Chappell and his Australian girlfriend, Kellie Wilkinson, both 24, were running a restaurant on the coast and had brought a friend, Tina Dominy, 25, who was on her first trip to Cambodia.

The taxi had turned south along Road 4, and were around 65 km by road from Sihanoukville near Taney when traffic was blocked by a truck. Khmer Rouge fighters from Regiment 27 had come down from a small base around Bokor and were shaking down travelers for money and other possessions. When they reached the taxi, the three westerners inside were puled out and marched off towards Bokor. The taxi driver was allowed to drive off.

It was the last time anybody outside the Khmer Rouge would see them alive, apart from local woodcutter who claimed to have spotted the trio in the Bokor area in May. Demands for a ransom of £100,000 were refused, and three sets of remains were found in Bokor in July 1994. They had been dead for a considerable time and the area had was booby-trapped with landmines.

On May 20, 1995 a man was arrested for the killings and taken to Kampot Military Region 3 headquarters where he was held for a month before being sent to Sihanoukville police. “I am very regretful. I am an uneducated man. I would have been shot had I refused the order,” Chuon Samnang, aka Mean, 34, told Reuters on June 26.

He told interrogators that he was working on the orders of his own uncle, Sam Bo, commander of Regiment 27. According to his confession, the three were shot on the morning following their capture. With four other Khmer Rouge they laid mines around the bodies, one of which killed a fighter when they were ordered to return and bury the corpses.

Somnang had defected his unit on April 18 1995 and returned to his family in Tram Kok district, Takeo province before his arrest. After a one day trial, he was given 15 years in prison. Five other guerrillas were convicted in absentia, including Sam Bo.

Train Hijack, End Of The Line

The train line running between Phnom Penh and Sihanoukville ran perilously close to the Khmer Rouge stronghold of Phnom Voar held by General Nuon Paet . The train service was attacked at least eight times in the 18 months before a fateful incident on July 26, 1994, and there were reports of collusion between the Khmer Rouge and state officials when it came to sharing the booty.

On that day, one hundred meters after the train passed a government checkpoint in Kompong Trach, around thirty Khmer Rouge ambushed it with B-40 bazookas. A leader of the raiding party had boarded the train earlier in Kompong Trach as a passenger. Armed with an automatic pistol, he quickly took control of the foreigners and directed the raiders by walkie-talkie. 13 Cambodians were left dead, including train security guards who were shot a close range. According to reports at the time the Khmer Rouge loaded their booty onto bullock carts and then built a campfire and cooked themselves a meal from the food they had captured.

Survivors, including many Cambodians, three Vietnamese, and three western backpackers were marched back to camp in order to ransom. Many of the Cambodians were later released, the Vietnamese killed and Briton Mark Slater, 28, Australian David Wilson, 29, and Frenchman Jean-Michel Braquet, 28, were taken to Andoung Chik village where they were held until their deaths.

Em Op, the train’s chief engineer, later said “It was an average attack.” A woman who had been riding the train and was briefly detained by the Khmer Rouge told The Phnom Penh Post, “I saw the foreigners lying…in a small cottage. They were crying. They were shackled at night.” She also said that a Khmer Rouge soldier told her, “I will send [the Western hostages’] bones to the authorities by the year 2000.”

The kidnapping was the end of the Khmer Rouge in the province, as journalists flocked to Kampot bringing the story to the world’s attention. As Khmer Rouge demands grew more unrealistic, from $50,000 to $100,000 to the cessation of all military aid from France, Britain and Australia to Cambodia, the government kicked out the foreign press and began amassing troops to encircle the area. By mid-August government forces began to shell the mountains with heavy artillery.

A reporter from the Sunday Times managed to conduct a radio interview with the hostages on August 19 “It is as if they are bombing to kill us,” Mark Slater said about the government attacks. “We hear…heavy machine-gun fire, mortars…rockets. We jump in the trenches and we are so, so scared.”

Later, a video of the men still alive was smuggled out, fueling further media outrage.

The Khmer Rouge officer who commanded the July 26 raid, Chhuok Rin, deserted on October 15, with around 150 of his man following a fall-out with Nuon Paet. He was promptly given immunity from prosecution, the rank of colonel in the RCAF, and $200. 10 days later the main assault to take the mountain was launched. Nuon Paet and a number of fighters retreated to Koh Sla. The three hostages were later found in a shallow grave in the area. The circumstances around their deaths remain controversial, but an official report at the time said they had been shot on September 28.

KR’s Kampot Last Stand

On December 3, Paet and a force of about 250 men were intercepted as they prepared a counterattack aimed at recapturing Phnom Voar. A government assault was forced back, and the Khmer Rouge again retreated to Koh Sla.

Koh Sla, in the north of the province was the final holdout for the Khmer Rouge in Kampot. At the beginning of December 1994, a full-scale assault was launched. The battle lasted for two weeks, with Khmer Rogue defectors from Phnom Voar under, now Colonel, Chhuok Rin assisting the RCAF troops.

During the fighting around 95 Khmer Rouge defected, along with 137 civilians. After the town fell on December 17, government troops were reported to have found 192 houses used by the Khmer Rouge and their families, several trucks, 6 saw mills, a rice mill and 1000 tonnes of rice.

“Kampot is a peaceful province from today,” Lieutenant General Sok Bunsoeun, deputy commander of RCAF division 5 in Kampot, told the Phnom Penh Post on December 21. “It is a great victory.”

Around 60 fighters remained around Bokor and Chhuok Rin was sent to negotiate their surrender.

The three commanders accused of the train hijack and hostage killings all blamed each other;

Nuon Paet was first believed to have escaped to Phnom Oral or Phnom Kravanh in Pursat province. He later was found living a good life in Pailin. He was lured to Phnom Penh for a supposed lucrative business deal in 1998. After arriving by helicopter he was arrested, put on trial and sentenced to life for the killings of Mark Slater, David Wilson and Jean-Michel Braquet.

Sam Bith, who had become a RCAF 2 star general being paid a monthly salary, could not be found for trial. Journalist Tom Fawthrop later tracked him down to Sdao, between Battambang and Pailin. He was living next to the local police station. Bith was sentenced to life for the same crimes on December 23, 2002. He died in Calmette Hospital on February 15, 2008, aged 74.

Chhouk Rin, given a life sentence in absentia in 2002 escaped to Anlong Veng, where he was captured in October 2005. His appeals were rejected.

Submitted by History Steve

Sources include:

Phnom Penh Post Archives

Associated Press Archives

Cambodia Daily Archives

The Independent Archives

Ben Kiernon

HRW- Cambodia at War

Getting Away With Genocide?: Tom Fawthrop, Helen Jarvis