This is Part Three of the series. Read PART ONE and PART TWO

Writer’s note: To avoid confusion with name changes, the term ‘Khmer Rouge’ is used in the article to refer to all forces of Democratic Kampuchea under the leadership of Pol Pot.

Border Troubles

1975: The newly installed Khmer Rouge regime was quick to live up to its ambitions in reclaiming land lost over the centuries to Vietnam. With the war almost over, Southern Vietnam in mid-April was in chaos, which the Cambodian communists seemed eager to exploit. Just two days after the fall of Phnom Penh the Vietnamese island of Phu Quoc (known as Koh Tral to Khmers), 15 km off the coast of Kampot, was shelled by forces under the command of Ta Mok’s son-in-law Khe Muth.

Early in May 1975 a Khmer Rouge raiding party briefly held parts of the island, reportedly raising the plain red flag of revolution on the beach. The Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam (the country would not officially unify for over a year after the fall of Saigon) sent helicopters to strafe the beach. The Cambodians were finally forced off when a contingent of North Vietnamese Army troops arrived to clear them from the island.

On May 10, 1975, Khmer Rouge forces occupied Thổ Chu Island, 120 km south of Phu Quoc and took around five hundred civilians to Cambodia. They were all killed. From May 24 to May 27, 1975, Vietnamese forces attacked and recaptured the island. The Khmer Rouge raided Thổ Chu Island again in 1977, but were repelled.

Cambodian claims to Phu Quoc were dropped in 1976, but border skirmishes continued, culminating in what is remembered in Vietnam as the Ba Chúc massacre.

Vietnamese Retaliation

Following Khmer Rogue shelling of border villages, attacks in September 1977 led to the deaths of around 1,000 civilians in Đồng Tháp province. On 16 December 1977, an estimated 60,000 troops from the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) assembled on the border and launched an attack, which overran the Cambodians and came to within 30 km of Phnom Penh before withdrawing on January 6, 1978.

Despite being delivered a humiliating defeat and being heavily outnumbered, Cambodian attacks across the border continued, including the overrunning of border posts in Ha Tien the same month. Another large Vietnamese force was then assembled all along the border, which infuriated the Khmer Rouge. The Vietnamese air force began targeting bombing raids on KR forces inside Cambodia, further raising tensions.

Internal purges of Khmer Rouge cadres began across the country, especially those who had previously had training and support from Hanoi. This led to many fighters and commanders, most notably from the Eastern Zone, defect across the border in 1977-78. Many of were viewed as being too close to Vietnam. Among these were Heng Samrin, Chea Sim and current Prime Minister Hun Sen. The purge of the Eastern Zone was carried out by cadres from Ta Mok’s Southwestern Zone.

A ceasefire to last for 7 months was requested by Cambodia on April 12, 1978, which was rejected by the Vietnamese. On April 17, 1978, a speech by Pol Pot was broadcast across Cambodia to celebrate the 3rd anniversary of Democratic Kampuchea. It was filled with vitriol against ‘the youn’ (a derogatory term used in Cambodia for Vietnamese). Three days later the most brutal assault against civilians in Vietnam since the war ended occurred. Khmer Rouge from the Southwestern Zone crossed the border into An Giang province and unleashed a terrible wave of violence upon the civilian population of the village of . At least 3,157 civilians were butchered, leaving just a handful of survivors.

Accounts say that many of the attackers lacked guns, and instead stabbed or bludgeoned men, women and children with knives and clubs. 40 died when grenades were thrown into a local temple where they had been sheltering.

After 12 days of bloodshed, Vietnamese forces finally responded, killing several Khmer Rouge as they retreated. Other reports say that the fleeing Khmer Rouge placed random landmines behind them, which may have killed up to 200 more in the weeks and months after the attack.

Invasion and Occupation

Enough was enough for the Vietnamese and a plan was hatched to remove Pol Pot and his deputies from power. Another Vietnamese incursion took place in June 1978 in the Eastern Zone, once again KR artillery was moved back and returned to the border and resumed shelling after the PAVN withdrew.

The situation was becoming global as the Khmer Rogue regime became increasingly reliant on Chinese support (later to invade Vietnam), and Vietnam signing a treaty with the Soviet Union guaranteeing military aid on 3 November 1978.

A home grown resistance force to overthrow the Pol Pot regime, The Khmer United Front for National Salvation (FUNSK), was formed in Kratie province on December 2, 1978. Ta Mok’s foe Heng Samrin was elected leader of the movement, which gave an air of legitimacy to the planned invasion and overthrow of Pol Pot by the government in Hanoi. 350,000 Vietnamese troops had been drafted and placed along the border.

As the threat of Vietnamese invasion loomed, Democratic Kampuchea had an estimated 73,000 soldiers in the Eastern Zone bordering Vietnam. Chinese-made military equipment was also rushed into place, which included fighter aircraft, patrol boats, heavy artillery, anti-aircraft guns, trucks and tanks. There were also between 10,000 and 20,000 Chinese advisers, both military and civilian in the country.

On December 25, 1978, Hanoi launched the offensive with twelve to fourteen divisions and three Khmer regiments with a total invasion force comprising of between 100,000-150,000. Five spearheads were launched simultaneously, with Kampot province being attacked by forces stationed in Ha Tien.

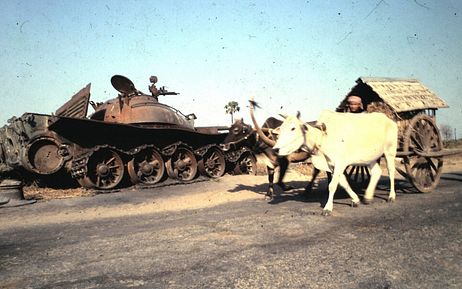

In the face of such an onslaught, heavy fighting was localized. A major engagement was fought around Tani, near Angkor Chey, but with few experienced commanders following the purges, and an underfed army, the Khmer Rouge scattered after heavy artillery and airstrikes pounded their positions. Some retreated to the west to regroup, while others melted into the countryside and mountainous jungles.

On January 6, 1979, the Việt Nam People’s Navy launched a naval landing, with the aim of capturing Kampong Som Port and Ream military base, to prevent the Khmer Rouge being resupplied by the sea. They faced the Khmer Navy Division 164 and Border Guard Regiment 17 who held the southern defensive line.

Brigade 101 Naval Infantry attacked and occupied a beach head at the foot of Bokor Mountain in Kampot Province, with what was the first successful landing-by-sea campaign carried out by the Vietnamese navy.

After establishing a position in Kampot, the Vietnamese quickly moved out towards Kampong Som and up to Koh Kong, along with taking control of the islands off the Cambodian coast.

In five days of fierce fighting on both sea and land, Vietnamese forces succeeded in wiping out Navy Division 164 and Border Guard Regiment 17 and took control of Kampong Som Town and the Ream Military Port, thus securing access to the coastal southeastern part of the country.

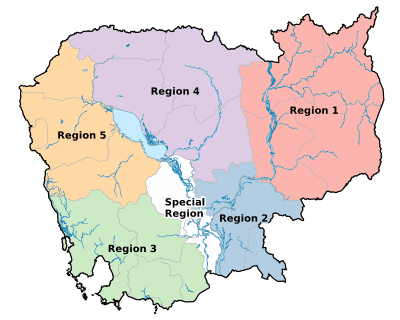

Kampot was part of the new Region 3, with the coastline stretching to Koh Kong renamed Naval Zone 5.

In interviews conducted by civilians fleeing the fighting, it was reported that the Vietnamese troops did not mistreat the population, and were well disciplined. However, needing to fulfill the military objective, weren’t immediately prepared for the humanitarian disaster that was the result of the Pol Pot regime’s agricultural policy.

Cambodian National Army

Recruitment for a new Cambodian national army began in earnest. As many as 200,000 Vietnamese troops were guarding the urban centers inside Cambodia, compared to around 30,000 Kampuchean People’s Revolutionary Armed Forces (KPRAF). Most of these were conscripted from former Khmer Rouge fighters, local militia units and the rural population, and was not an easy task due to the physical health and condition of those who had survived the Khmer Rouge regime and subsequent famine.

To begin with young men were pressganged into service. In an off the record interview in 2016, one man told me his account on how he joined the new army. “After Pol Pot had gone, the Vietnamese came to my village in Kampot to look for new soldiers. I was still a strong boy, so they took me to Vietnam to study.” He rose through the ranks and was, at the time of the interview, a 3-star General in the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces, and a fluent Vietnamese speaker.

All Cambodian males aged 18-35 faced an obligation of three years military service. This was raised to five years in 1985, due to shortages in manpower. Men from Kampot, along with all other provinces, were also drafted and taken to the Thai border from 1985-89 to build the ill-fated border defense zone, known as the K-5 plan.

Morale was generally low among the conscripts, who were paid $4-5 a month, with a rice ration of 16-22 kg. Desertion was common, especially among the rural men, who were needed back on their farms during the planting and harvesting season.

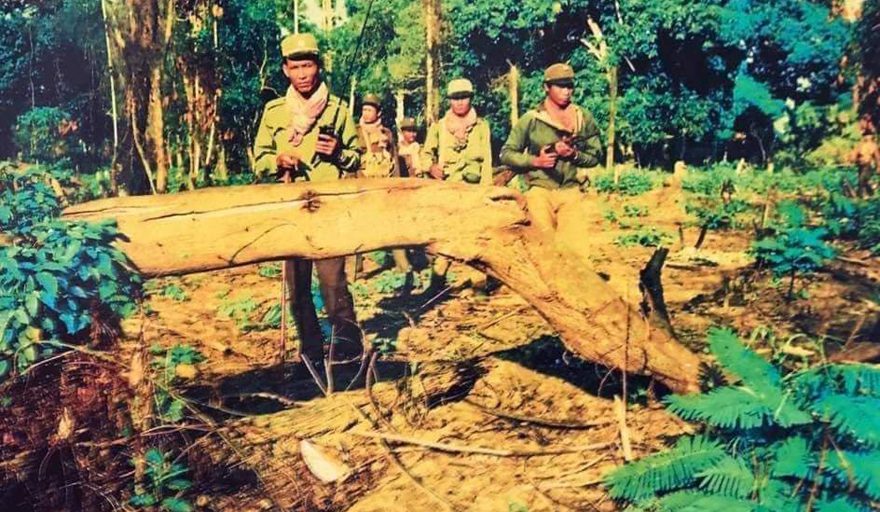

Mr. Ly, a former neighbor from Kampot, joined what he called the “Hun Sen” army later in the decade. He was a part of a small patrol unit, of around a dozen to thirty men who would spend days or even weeks in the jungles around Kampot, Kampong Speu and Pursat on search and destroy missions. Casualty rates were high, from small arms fire, RPG’s, and especially landmines and booby traps.

Opposition in Exile

Across the border in Thailand, a proclaimed legitimate government in exile, the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK) was formed in 1982 with an alliance between Sihanouk loyalist group FUNCINPEC, the right-wing nationalists of Khmer People’s National Liberation Front (KPNLF) of Son Sann (the armed group, the KPNLAF was led by former FANK commander Lieutenant General Sak Sutsakhan) and the Khmer Rouge army (National Army of Democratic Kampuchea), led by Son Sen, after Pol Pot stepped down. Although mostly hidden from view in diplomatic circles, the Khmer Rogue were the only truly viable military resistance group able to operate within Cambodia, using their battlefield experience of guerrilla warfare and old supply routes.

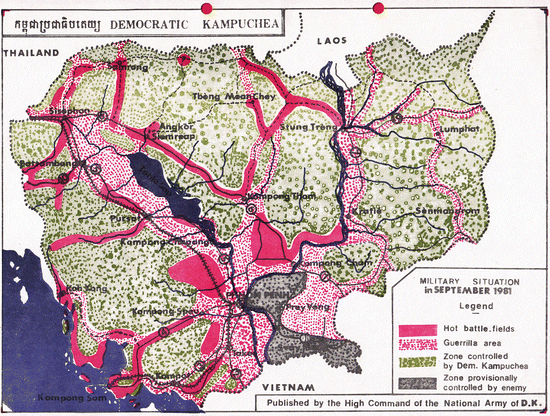

The NADK

The massive 1984-85 Dry Season Offensive launched by Vietnam along the Thai border (along with the limited success coming from the K-5 Plan) all but destroyed the fighting capacity of the non-communist armed factions. Son Sen, the former Khmer Rouge Minister of Defense and leader of the National Army of Democratic Kampuchea (and former chief of the political committee for Kampot, Takéo and Kampong Speu in the late 1960’s) changed tactics. Rather than continue border incursions, efforts were made to hold remote villages and form a rival authority outside of the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) and Vietnamese hands. The re-branded Khmer Rouge had remained within the Kampot region, with significant bases at Phnom Voar and Koh Sla. The forested slopes of Bokor were also used as a refuge.

Koh Sla, around 40km north of Kampot town, became the key supply and operational base for Khmer Rouge in Kampot, Takeo and Kampong Speu provinces from the early 1980’s. Setting up an alternative administration in the area, civilians grew crops such as rice which was distributed among rebel groups in the area. Among the commanders who would later rise to prominence were Nuon Paet at Phnom Voar and, in Koh Sla, Sam Bith, who had been Ta Mok’s deputy during the Democratic Kampuchea regime.

From these centers, hit and run raids were carried out, with RPG’s being deployed against armored convoys along the major road links. Booby traps and landmines were then set as they retreated, killing and wounding more PAVN and KPRAF forces as they counterattacked. Fighting was heavier in the north and west of the country, as arms were smuggled across the Dangrek Mountains and from Trat, with the Khmer Rouge still using the Thai border as a semi-autonomous headquarters.

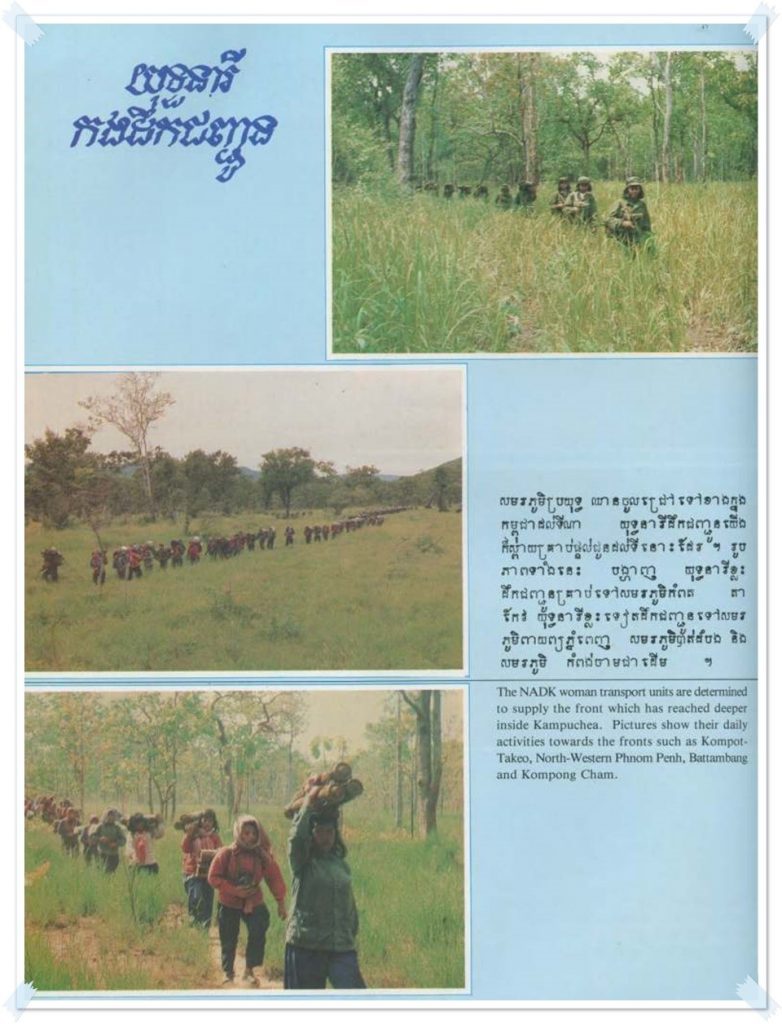

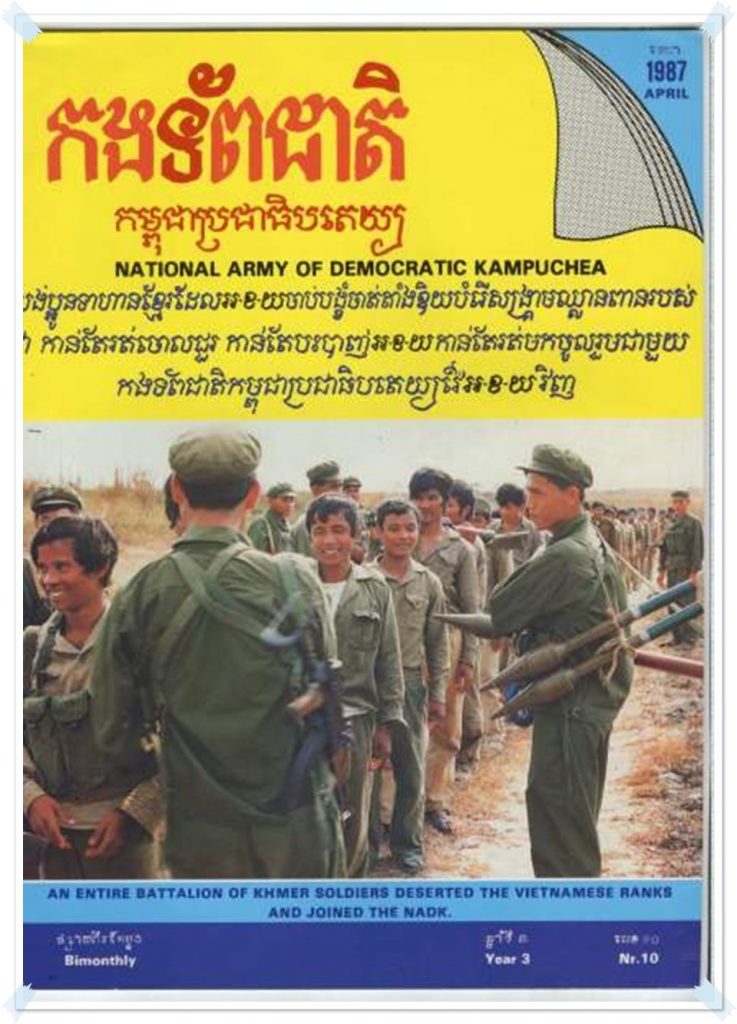

The NADK even published a bi-monthly color propaganda magazine, showing preparations for attacks, defecting KPRAF soldiers and happy civilians living under their control. (See more HERE)

Fearful of a southern incursion the Vietnamese Navy was active along the Kampot coast, with several incidents, such as in December 1983, when Vietnamese gunboats opened fire on a fleet of ten Thai fishing trawlers about 20 miles off the southern Vietnamese coast, seizing five trawlers and capturing 130 fishermen.

Hundreds of thousands of civilians across the country left for border camps during the 1980’s. Many Vietnamese civilians started coming in from the east. Some of these were returning back to previous homes having fled persecution over previous decades, while others were looking for opportunities in a largely underpopulated countryside. A CIA report from the mid-1980’s estimated that 600,000 Vietnamese had settled, mostly in Eastern Cambodia, but including Kampot, although it is likely these numbers were heavily inflated for political reasons.

The End of Occupation

On 26 September 1989, 10 years, 9 months and 1 day after the military operation rolled over the border, the last Vietnamese troops left. 26,000 men and their equipped headed along National Road 1 to Ho Chi Minh City. Over 55,000 of their professional soldiers and volunteers had died in Cambodia. The Cambodian army’s losses were perhaps as much as four times higher.

As negotiations for a settled peace by all parties got underway, it became clear that the Khmer Rouge were not willing to disarm. Nate Thayer even reported that March 1991, Vietnamese units re-entered Kampot Province to defeat a Khmer Rouge offensive.

The Vietnamese had gone, but the Khmer Rouge continued the fight against the state. The train linking Phnom Penh with Kampot was hit by rocket fire on 30 July 1990, and Khmer Rouge forces in the province launched a series of attacks on 6 August, according to Phillip Hazelton, an Australian aid official who was in Kampot at the time.

Kidnapping, ransom and banditry committed by Khmer Rouge soldiers were common place in the province.

A May 1991 quote from Steven Erlanger of the New York Times describes the interim period after the Vietnamese withdrawal and before the United Nations arrived.

“The Khmer Rouge, too, pursue their war of disruption and intimidation. To some villagers, the Khmer Rouge show a friendly face, buying ducks and rice, and sometimes they marry village women. They speak to the villagers about politics. But often they kidnap or kill village heads and teachers, and take the young men to serve as porters.

The Khmer Rouge say they are concentrating now on “political work.” Six weeks ago, new arrivals at a refugee camp in Kampot said the Khmer Rouge came to their village and took 100 people with them to the forest for “education.” They were told that there are two sides in the Cambodian struggle: the Phnom Penh regime, which is corrupt, and the side of Prince Norodom Sihanouk, Cambodia’s former King, with whom the Khmer Rouge are allied.

After four days, the villagers were freed, minus a handful of children. They were told that if the election went well, they would see their children again. If not, they would not.

“How will they vote?” asked an experienced aid worker. “More important, can the United Nations prevent this kind of intimidation?“”

Other kidnappings in the province were reported in September 1991 and January 1992, mostly of children.

Paris, But No Peace

After the Paris Peace Agreement was signed on October 23, 1991, the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia prepared to restore peace and civil government with free and fair elections, the Khmer Rouge showed no sign of surrendering their holds in Kampot and other provinces.

In Kampot Province, the Khmer Rouge stepped up their raids following the agreement, according to foreign aid officials stationed there.

Reuters reported: “The Khmer Rouge occupied Dang Tung district and raided Kompong Trach in November, aid workers said. They hit Chum Kiri in December, killing a teacher and torching government buildings. In other attacks they were said to have burned houses of people trading with Vietnamese. They are blamed for a run of kidnap[ping]s….” In the village of Kon Sat they killed 2 people in November. A villager told a journalist: “I would like to believe in peace, but every day the Khmer Rouge comes down to our village and steals everything and sometimes kills people. Right now it’s impossible to live here.“”

Next, Part 4: Bandit Country

Thanks to HISTORY STEVE for CNE