Pre-Independence Kampot

Kampot came to prominence under 19th century French rule with the Circonscription Résidentielle de Kampot puuting the town in contraol of the areas of Kampot, Kompong-Som, Trang, and Kong-Pisey.

The loss of the Mekong Delta to Vietnam turned Kampot into the only port with access to the sea, before Kampong Som (later renamed Sihanoukville) became developed. And proximity to the Vietnamese border, less than 50 km to the east, gave the town extra significance.

An 1889 French colonial census reported a multi-ethnic community. Kampot town was split into “Cambodian Kampot” on the Prek-Kampot River and “Chinese Kampot” on the right riverbank of the west branch of the Prek-Thom River. Nearby was also a Vietnamese village, called Tien-Thanh and another Vietnamese village and a Malay enclave also existed on Traeuy Koh Island. Additional villages of mixed ethnicity were also listed.

The strategic location of the border and coastline inevitably saw a military build up around the province as tensions rose in the region following independence.

‘Issarak’ was the loose term given anti-colonial militias pre-independence. They encompassed a broad political spectrum, while others were little more than ‘patriotic’ bandits who used fighting the French as an excuse to carve out a rural fiefdom.

By 1948, Sangsariddha, a Khmer-Vietnamese had crossed from Trà Vinh in the Kampuchea Krom area of southern Vietnam, and led a platoon of fighters near Kampot. Other groups operating on either side of the border around Ha Tien.

The United Issarak Front ( សមាគមខ្មែរឥស្សរៈ, Samakhum Khmer Issarak), a Cambodian anti-colonial movement active from 1950–1954 was a left-wing branch of the Khmer Issarak movement.

The founding conference of the UIF was held in Kompong Som Loeu, then part of Kampot province, between April 17–April 19, 1950. Around 200 delegates were at the conference, including 105 Buddhist monks and Ung Sao, a Viet Minh general. Khmer, Vietnamese and Laotian flags were displayed. Son Ngoc Minh (1920–1972), also known as Achar Mean was elected the movement’s president, with Tou Samouth, also known as Achar Sok, serving as his deputy. He would later go on to be mentor to Saloth Sar, better remembered as Pol Pot.

The group would go on to wage an armed struggle against the French, with the support of around 3,000 Viet-Minh irregulars. A major coup came for the rebels In February 1953, when UIF and Viet Minh forces ambushed and killed the governor of Prey Veng.

The Issarak in Kampot were had a ‘central office’ around La’ang and headquarters of the Southwest zone in the Koh Sla river valley, about 35 kilometres north of Kampot town in Chhouk district. Following several raids and as many as 30 bridges in the province destroyed by Issarak rebels, the Governor of Kampot made plans to restrict travel and residence around the area.

At the time of the Geneva Peace Conference of 1954, it is estimated that UIF controlled about half of Cambodia. After being disbanded in 1954, many of its members would go on to become leading lights of the Cambodian communist movement.

The next decade would be relatively quiet in the southwest, but other incidents across the country would eventually have consequences felt.

War In Vietnam

1965 was a significant year for Cambodia as a whole. The escalation of the war across the border in Vietnam saw a large number of Khmer-Krom refugees, along with ethnic Chams (and undoubtably some Vietnamese) cross the border. The Khmer-Krom refugees were allocated land in government settlements established in Kampot, Kirirom, Kompong Chhnang (Chriev) and Ratanakiri and Battambang, causing resentment among local Khmer communities, many of whom did not own the land they farmed.

In May of that year, the Cambodian government cut all diplomatic ties with the USA, by far the largest provider of aid to the kingdom. A deal between China and Cambodia saw shipments of arms being funneled into South Vietnam via Sihanoukville; The Sihanouk Trail.

The CIA, worried by the intentions of an often-erratic government under Sihanouk, began intelligence gathering in Kampot. They identified army bases in Kampot at Kampong Trach (with a barracks and airstrip), more barracks at Tuk Meas, a military camp near Tonhon, and the airport near Kampot town along with a cement works being built by China.

The CIA noted smuggling across the border, which had always been endemic, and provided a livelihood for many people. Viet Cong and supporters were buying explosives (especially potassium chlorate, used for Viet Cong bombs), food, medical supplies and radio equipment smuggled from the region of Kampot and other border provinces.

The “Kampot – Ha Tien area” was identified as a “spot location of Viet Cong occupancy”. A deserter interviewed told his interrogators of an NLF (Viet Cong) controlled clandestine radio station just inside the Cambodian border from Ha Tien, on a hillock near a village called Luc Son (close to road 33). The village also had two battalions of Cambodian Army troops based there.

On 3 March 1968, the Cambodian navy overhauled an arms-laden junk just off the coast of Kampot Province, at a point some fifteen miles west of the South Vietnamese Island of Phu Quoc. Initial interrogation of the crew – three Vietnamese, two Cambodians — showed that the arms were bound for “Red Khmer” rebels in the Cambodian interior. Subsequently the story was changed to indicate that the arms were headed not for the Red Khmers in Cambodia, but for the Viet Cong on the South Vietnamese mainland. But the new story and the circumstances surrounding it were highly suspect, according to a CIA cable:

“According to a report from Phnom Penh, two Viet Cong representatives showed up at the office of the Cambodian Army G-2 on 8 March “to negotiate for the release of the crew.” After assuring the G-2 that the arms vessel was headed for Viet Cong territory, they reportedly left a two-inch-thick package of 500 riel notes “as an earnest” even though the crew had already been. shot. After the riels — worth some $3000 — changed hands, Cambodian intelligence began giving a different account of what happened. Whereas the original story indicated the junk was intercepted 15 miles west of Phu Quoc — that is, far from the Viet Cong but close to Cambodian rebels — the new story indicated the vesse had gone aground on a Cambodian island only 2 1/2 miles from Viet-Cong infested Phu Quoc, having been “blown ashore.. . during a storm. One trouble with the new story was that there had been no storm. A review of Zone a2 weather reports of 1 through 5 March 1968 show that the weather around Phu Quoc was balmy and that the winds were light. The weather reports included those from Sihanoukville and Kampot.

**The reports came from an agent network run by the US Navy. Never confirmed, they have a ring of truth. The information they convey is concise, plausible, and of a type which local informants can provide.”

American bombing of Cambodia began in 1969, and although Kampot was not targeted as heavily as the southeastern zone, especially around the ‘Parrot’s Beak’ and ‘Fish Hook’ areas of Svay Rieng and Kampong Cham, the province did not escape the B-52’s. MK-82 bombs which failed to detonate are still being uncovered around the province.

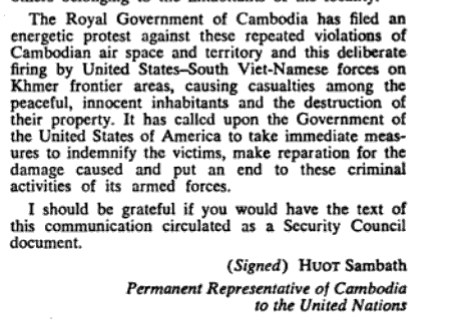

It was by now apparent that the North Vietnamese not only wanted to use Cambodia as a safe zone, but were actively supporting local communists in an uprising. The bloody and complicated Cambodian Civil War was beginning.

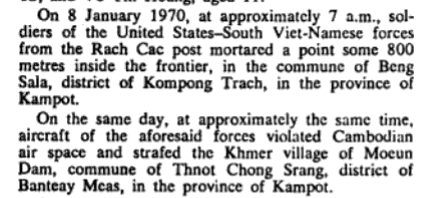

Not only was Kampot’s airspace violated. The following are extracts of the many complaints lodged with the United Nations by the Cambodian government in 1969-70.

Following the deposing of Sihanouk in March 1970, the new Khmer Republic (formally declared 9 October 1970) under Lon Nol took a hostile approach to the North Vietnamese operating inside Cambodia. This put Kampot on the front line, and as the town garrison fortified, much of the surrounding countryside was in the control of the Khmer United National Front, known as FUNK, an alliance of those still loyal to Sihanouk and communists from both Vietnam and Cambodia. Note; it wasn’t quite as simple on the ground, with many branches and groups nominally joined together. For the sake of convenience, the term FUNK will apply to all non-government Cambodian forces.

The Khmer Republic

Facing them were the army of the Khmer Republic (FANK, also sometimes referred to as FARK), which, although high in numbers were poorly trained, poorly equipped and often led by massively corrupt officers. A major problem with the Cambodia army was its weapons. The French initially left behind military equipment and supplied the army after independence. The USA was halfway through modernizing the armed forces when Sihanouk cut off all aid in 1965, and Chinese and other communist regimes then stepped in; it was an army with 3 different equipment systems, weapons and ammunition.

A classic guerilla war scenario ensued, with the FUNK aiming to isolate the FANK inside the towns, while major roads were blocked, putting a stranglehold on supplies and the economy. Almost immediately after the Republic was declared, FUNK forces took over, and began administering large swathes of rural areas and the local population.

Government troops, which had previously coexisted with the rebels along the border, were forced away, leaving frontier villages under the control of the FUNK or North Vietnamese Army (NVA)/ Viet Cong (VC).

The Hot War

The beginning of the Khmer year of the dog in April 1970, justs weeks after Lon Nol had assumed power, began badly for the Republic. Tuk Meas was captured on April 21 by the NVA/VC, with Kampong Trach falling after an attack on April 29.

At the same time the Cambodian Campaign was launched by South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) and US troops. The aim was to destroy communist bases around the hot zones of the Parrot’s Beak and Fish Hook, where tens of thousands of communist forces were thought to be sheltering. The new Cambodian government were not informed until the operation was underway.

Rather than face a full assault, NVA and VC units provided stiff initial resistance, allowing the bulk of their troops to retreat deeper into Cambodia to the north or to the west. FUNK forces either withdrew to their other bases or hid themselves among the civilian population.

Military Region 2

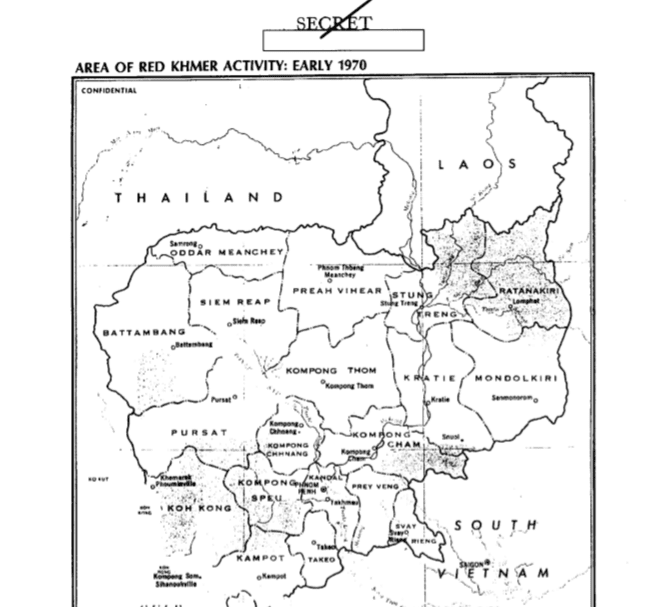

In May 1970, Kampot and Takeo came under the new Military Region (MR) 2, with the following forces:

- Takeo: 2,500 men,

- Ang Ta Som: 1,700 men

- Kampot: 1,100 men

- Kampong Trach: 170 men.

By early May, reports from the CIA noted the capture of parts of Kampot town by FUNK forces. With support from ARVN troops, the area was retaken two days later.

By May 11 there were reports an NVA (probably from the NVA 1st Division) had entered the town with orders to destroy bridges. It took ARVN a week to dislodge them, but some remained around the high ground outside the town.

The coast was next to come under attack. Kep was taken for a day on May 14, recaptured in a counter-attack and raided again ten days later. Prek Chak, just across the border from Vietnamese Ha Tien remained under VC control.

By June, the only cement works in the country at Chakrei Ting, eight kilometres north-east of Kampot, had been damaged by the fighting, and was put out of action. It was to become a stage for fierce fighting over the coming weeks, changing hands between FANK and FUNK several times.

Kampot and Sihanoukville were cut off from road and railway connections to Phnom Penh, with the train tracks destroyed and several bridges blown up.

Meanwhile, ARVN forces were becoming unpopular with locals, with reports of villages cleared, airstrikes and wide-scale looting by the Southern Vietnamese soldiers. The US withdrew from Cambodia on June 30 and ARVN troops on July 22, reportedly to the disappointment of the Cambodian government, who were hoping for a permanent American presence in the country.

In the vacuum that followed, FANK bolstered its ranks in MR2 zone, which stretched from Koh Kong to the Vietnam border and up to Road 4 in Kampong Spue.

The 3rd Infantry Brigade were stationed in Kampong Som (Sihanoukville), the 6th Infantry Brigade (made up almost entirely of Khmer-Muslims) was split between Kampot and Kampong Cham, and in the Takeo section of the region, the 8th Infantry Brigade centered around the border at Chau Doc.

At the northern section of MR2, the 13th Infantry Brigade were tasked with defending Road 4 in Kampong Speu and the 14th Infantry Brigade was rebuilt with elements from anti-aircraft and artillery units after being heavily depleted in battle were holding Road 3.

.

The rest of 1970 saw fighting to the northwest of MR2 with the launch of Operation Chenla. Initially successful, a NVA commando raid on Ponchentong airfield saw many soldiers from the frontlines recalled to defend the capital.

There were some reports around this time of unofficial ceasefires between the FANK and FUNK, with local commanders agreeing not to attack each other unless provoked.

Within the ranks of the FUNK, splits were beginning between the COSVN (the main NVA controllers), the Viet Cong, pro-royalist factions and branches of the Cambodian communist movements, who took opposing sides over the question of Hanoi’s influence.

Tensions were flaring up in the so-called Southwestern Zone (roughly the same area as FANK’s MR2). A relatively minor faction of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) was growing in strength around Kampot and Takeo. A leading force among this group was a former child monk and staunch anti-Vietnamese communist from Tram Kak in Takeo province. His real name was Chhit Choeun, others knew him as Nguon Kang, and later Brother Number Four. His nomme de guerre is better known to history as Ta Mok and to his foes as ‘The Butcher’.

Compiled by History Steve for CNE

*Notable sources include CIA Archives, David Chandler, Micheal Vickery, Be Keirnan, Lt. Gen. Sak Sutsakhan, Kampot-ontheedge.org

2 thoughts on “A Military History Of Kampot Part 1: Colony-Civil War”