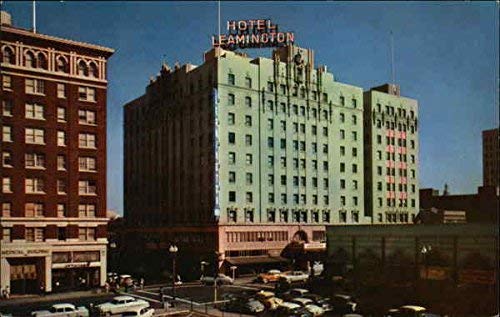

Oakland, California, 1975: A telex machine in an office inside the Leamington Hotel whirs into action with a message sent from across the Pacific. A name is printed, that man is contacted and strongly encouraged to send a résumé, to be forwarded to the office of a construction company in downtown Bangkok.

1975: The war in Vietnam was all but over, with the USA reeling from a near total defeat and the loss of over 57,000 service personnel killed or missing.

The Southeast Asian conflict had lost public and political support in America, with combat operations ending in Vietnam by 1973. The Case–Church Amendment legislation was was approved by the U.S. Congress in June 1973 and prohibited further U.S. military activity in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia without Congressional approval. This included air support.

Military and economic aid still flowed to Saigon, and to the government of Lon Nol in Cambodia, which had lost control of most of the country. After five weeks of heavy fighting, Kampot fell to the Khmer Rouge on April 2, 1974. The communist forces then advanced to capture Oudong to the northwest of the capital. By the end of the year forces loyal to the Khmer republic held little more than outposts around the capital and lowland provincial towns including Battambang and Siem Reap. Historians continue to argue over the issue, but airpower does appear to have prevented the communist forces seizing these targets earlier in the 1970’s.

Watergate, resignations and criminal trials came to Washington, but with so much blood, sweat and tears invested in Indochina, along with the billions of dollars spent, the US was reluctant to completely sever ties with former allies (the New York Times in 1975 reported that the cost of the war in Vietnam alone was equivalent to spending $7000 on every South Vietnamese citizen, around $33,435 today).

With most farmland firmly in enemy hands, the food situation in Phnom Penh was critical, and by 1973 weekly cables reporting the rice situation in the capital were being dispatched to Washington. Malnutrition, especially among the young was becoming common by 1974.

1975 began with the final push on Phnom Penh by the Khmer Rouge. The plan was to cut off the last supply route to Saigon; the Mekong River, and starve the city into submission. By the end of February, the Khmer National Navy (MNK) had lost a quarter of its ships, and 70 percent of its sailors had been killed or wounded.

With the Mekong abandoned by the army, all supplies needed relied on airdrops into Ponchentong airport. Under the Case-Church Amendment, military hands were seemingly tied by Congress, but out of the shadows stepped a silver-haired construction contractor by the name of William H. Bird.

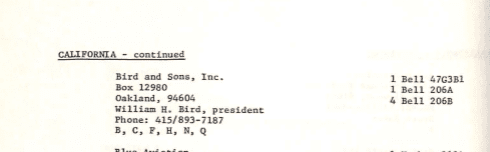

Bird began his career in construction during World War II, with contracts to build gun emplacements and anti-aircraft batteries along the Panama Canal. The company Bird & Sons was founded in Oakland in 1956 by Scott Bird, father of William and his brother, Scott Jr. Scott Sr.

The family firm moved to the far east, opening the Philippine Rock Products Inc. and later the Thai Rock Products Co. Ltd. In 1959. The company supplied construction materials, and was awarded a US Navy contract to build 5000 meters of runway at Wattay Airport outside Vientiane in Laos.

Around the same time Bird invested in a single fixed-wing plane and started Bird Air as the aviation arm of Bird & Sons. For the next six years Bird Air would run a contract with USAID, providing a full charter service in Laos, which led to rumors of involvement with the C.I.A., the company denied.

Bird sold the company, which had expanded to 22 planes in 1965, to Continental Air Services, and agreed in the contract to keep out of the air-charter business for 5 years.

Back in Oakland, Bird purchased the Leamington Hotel for $2 million ($16.3 million today). Aviation pioneer Amelia Earhart had once kept an office in the building to plan her final trip. There he hosted POW’s released from Vietnam and there families, telling them he ‘made a fortune over there, and I’d like to do something for the people who fought the war.”

After the contract clause expired, Bird Air returned to war-torn Laos chartering helicopters.

In 1974, with the Case–Church Amendment limiting any direct government involvement, a contract worth $1.7‐million ($8.2 million today) was signed with Bird Air to supply five six‐man crews to fly the Cambodian airbridge into Ponchentong from September, 1974 to June, 1975. Under terms of the agreement, no more than 200 US servicemen were permitted to be in Cambodia at one time.

Bird admitted in a 1975 interview that he had been tipped off about the upcoming contract and took the time to prepare personnel before the tender was made public. The source of the inside information was never revealed.

The United States Air Force was to supply the five C‐130 cargo planes, provide all fuel, maintenance and even give physical examinations and refresher physiological training for the crew members. This was given the term ‘government furnished’ rather than ‘leased’; a move that was seen by many at the time a skirting around the rules.

Those employed by the contractor, a clause stated, were to be considered civilians ‘in no way acting as representatives of the United States Government’. No press statements were to be given, unless authorized by the military beforehand, and the contractor took sole responsibility for any damage, injuries or deaths incurred during operations.

The first drop by Bird Air was made in Phnom Penh on September 26 and all USAF personnel were replaced by October the 8th.

To make matters even more murky, the original contract was signed on July 11, 1974, with an Air Force master sergeant, Warren H. Shouldis, representing the United States Government. The same contract was not officially approved until January 28, 1975 by Col. R. B. Lovingfoss, director of procurement. By the time the deal was official, Bird Air had been flying planes supplied by the USAF for four months.

The C-130 aircraft were based out of U-Tapao in Rayong, Thailand and began flying up to 10 times a day to Ponchentong. Supplies were also being ferried in from Saigon by three other private carriers using their own planes—Flying Tiger Line, Trans International and Airways International.

In February of 1975, with the Mekong supply route lost, the contract was upgraded to $2.6 million (roughly $12.6 million at today’s rates) and an extra 7 crews and DC-6 aircraft brought the total number up to 73 men from Bird Air flying the route.

With great danger came great reward. Crew members hired were all ex‐Air Force men and, although were officially serving in the military, some, it was admitted may have been reservists

The men were paid around $3.000 a month (around $11,000 in today’s rates). Bird Air is paid an average of $450 a flight hour—or $900 for the round trip between U-Taphao and Phnom Penh. Bird told the Washington Post in 1975 “I’m only making 12% on this one”.

“You get a good captain and ask him if he knows someone who is really qualified…. They have a good grapevine.” Bird was quoted as saying.

Mr. DeRonde, the former Bird & Sons vice president, described how some names would come through from Bangkok by teletype to the Leamington Hotel. “We tell him he is recommended by Bangkok and to send us a résumé,” he said. “In most cases we never see the men.”

At its peak, as many as 30 drops a day were the only lifeline between Phnom Penh and the outside world, a fact which did not go unnoticed by the Khmer Rouge.

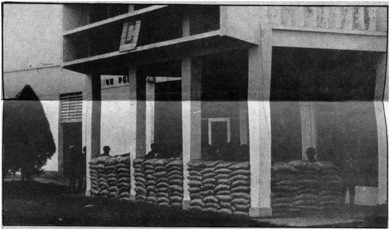

On 5 March, Khmer Rouge artillery at Toul Leap, around 10 km north-west of Phnom Penh, began shelling Pochentong Airport. Republican army (FANK) troops managed to recapture Toul Leap on 15 March and ended the shelling, but Khmer Rouge forces continued to close in on the north and west of the city and were soon able to fire on Pochentong again. By late March the FANK maintained a defensive perimeter some 15 km around central Phnom Penh. In the northwest, the 7th Division was in an increasingly difficult position, with the front being cut again around Toul Leap. The 3rd Division, located on Route 4 around Bek Chan, 10 Km west of Pochentong was cut off from its own command post at Kampong Speu.

Hundreds of shells began to rain down on Ponchentong airfield. The Khmer Rouge artillery was not well ranged, and most landed in disused parts of the airport. Nine Cambodia airport workers were killed, and many more injured during the shelling.

Turn around time needed to be fast, and aircraft were generally on the ground for no more than 20 minutes.

On 22 March rockets hit two supply aircraft (a C-130 and DC-8), forcing the US Embassy to announce on 23 March a suspension of the airlift until the security situation improved. The Embassy, realizing that the Khmer Republic would soon collapse without supplies, reversed the suspension on 24 March and increased the number of aircraft available for the airlift.

On 1 April the Khmer Rouge overran Neak Luong and Ban-am, the last remaining FANK positions on the Mekong. The Communists could now concentrate all their forces on Phnom Penh. The shelling of the airport continued, and the situation was, by now untenable. Air Force planes, along with Bird Air aircraft began evacuating American citizens and some civilians on 3 April on return flights. Around 1000 were taken to Thailand, easing the pressure on the helicopter evacuation ‘Operation Eagle Pull’ which took place on the 12th.

Bird Air crews continued to fly for 5 days after all Americans had pulled out, with the final drop on 17 April, the day that Khmer Rogue forces entered Phnom Penh.

During the final 8 weeks of the Cambodian civil war, Phnom Penh was entirely reliant on supplies brought in by air. The civilian crew landed an average of 1100 tons a day during this time, as well as making drops over other areas still in the hands of the FANK.

A few weeks before the fall of Phnom Penh, William H. Bird summed up the role he was playing in keeping a city alive.

“I am rather proud of what we are doing.”, he said.

“I think we have a commitment and I am proud the United States is doing the airlift and helping to supply the people of Cambodia. I am a contractor and I finish the contract, good or bad. I hope we continue our commitment. If we can hold out until the rainy season, there can be a regrouping. I am not a military man so I don’t know exactly what you do. I am a poor old contractor who just works his tail to the bone.”

After the war ended, William H. Bird appears to have faded from public view. Neither his wife’s name, or the names of any of his staff were permitted to be published at the time. However, there was confusion at the time as, also in Bangkok was a Willis H. Bird who was a former United States civilian air intelligence agent and who was indicted in 1962 on charges of seeking to defraud the United States Government on construction contracts in Laos. The two Mr. Birds were never linked, and Willis H. Bird never stood trial.

“I think that everybody wants to pin it,” he told Steve Talbot, a reporter for Internews, a California‐based international news service, in February 1975. Nevertheless, Mr. Bird added, his company only held a negotiated contract with the Air Force. “It in no way could be called a C.I.A. operation,” he said.

Submitted by History Steve for CNE

Sources: New York Times ( Ralph Blumenthal ), Tactical Airlift (Ray L. Bowers), Philip Brooks, 9website, AP, Wikipedia.

I flew a Continental Air Services C-46 almost daily on a round trip from Bangkok to Phnom Phen from 21 Jan 75 until 10 April.

Les Strouse

I was a close friend of the William Birds son, Bill, in 1964-1966. If Bill is still alive I’d like to hear from him.

I have been working for Bird & Son, Inc at beginning of 1964-1967

And Bird Air/LAD of 1971-1974

I love Bird & Son and Bird Air for my career of Supply Manager & Operations Manager as well as Security Clearance

Thank you Mr. William H. Bird and entirely Bird families

Hi Andy,

My name is Marcia Bird. I was Bill Bird’s wife for 30 years. I have heard your name mentioned over the years. He is currently living in San Diego near one of our daughters house. Unfortunately he is suffering from Alzheimer’s. He has difficulty speaking and is wheelchair bound. He however, still has his keen memory and still loves a good story. I would love to tell him that you were trying to find him. Did you know him from Menlo School? I live in Palm Desert, CA and visit him every Saturday at his assisted living home.

Hope this reaches you!

Best Regards,

Marcia Bird

Hi Marcia, I am afraid that we have acquired this site from the previous owner, who we are not in contact with. I am not sure how you can contact him. Best