The Cambodian-Spanish War 1593-97

The 16th Century

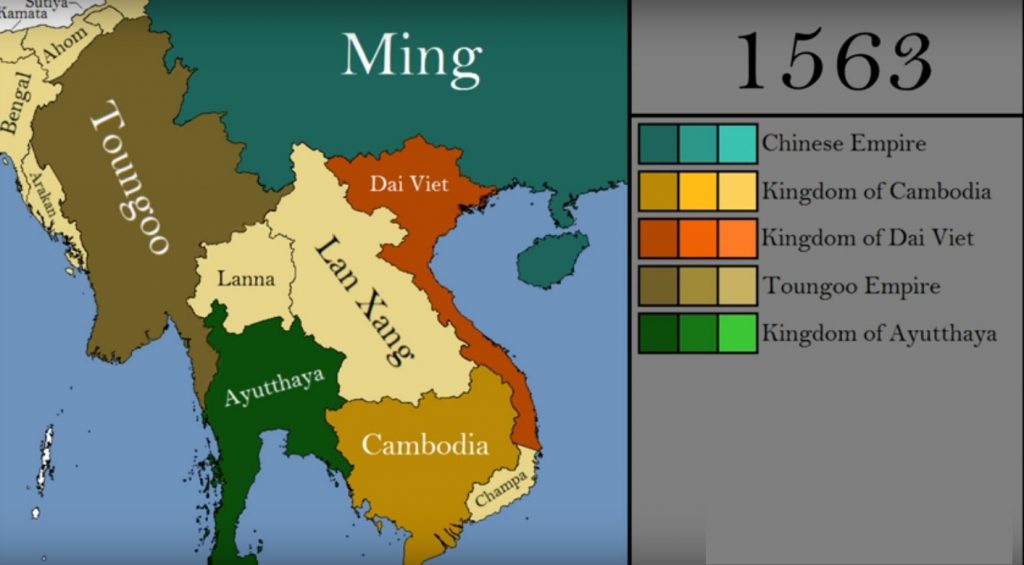

The Angkorian age is generally considered to have ended by the mid-fifteenth century, following decades of subjugation by various rulers of the Thai kingdom of Ayutthaya leading to the relocation of the capital to Longvek in around 1431.

The next 160 years would be a complicated time for the region as local kingdoms battled each other for territory, much of which had been under the control of the Angkorian Empire at its peak.

The Ayutthaya kingdom, to which Cambodia was little more than a vassal state was locked in almost constant conflict with the Taungoo dynasty from Burma, who were also at war with the kingdom of Lan Xang in what is now Laos.

Along the Gulf of Tonkin, the once mighty Kingdom of Champa was being eaten away by the increasingly land-hungry Dai-Viet dynasty.

Into this mid-16th century maelstrom of shifting borders stepped the first Europeans, eager to trade and keen to push out the Arabians who controlled the spice route monopoly from the Far East.

Ever willing to push the limits of business with the main powers at the time, British, Dutch, Spanish and Portuguese arrived making and breaking alliances between local leaders and themselves.

Longvek

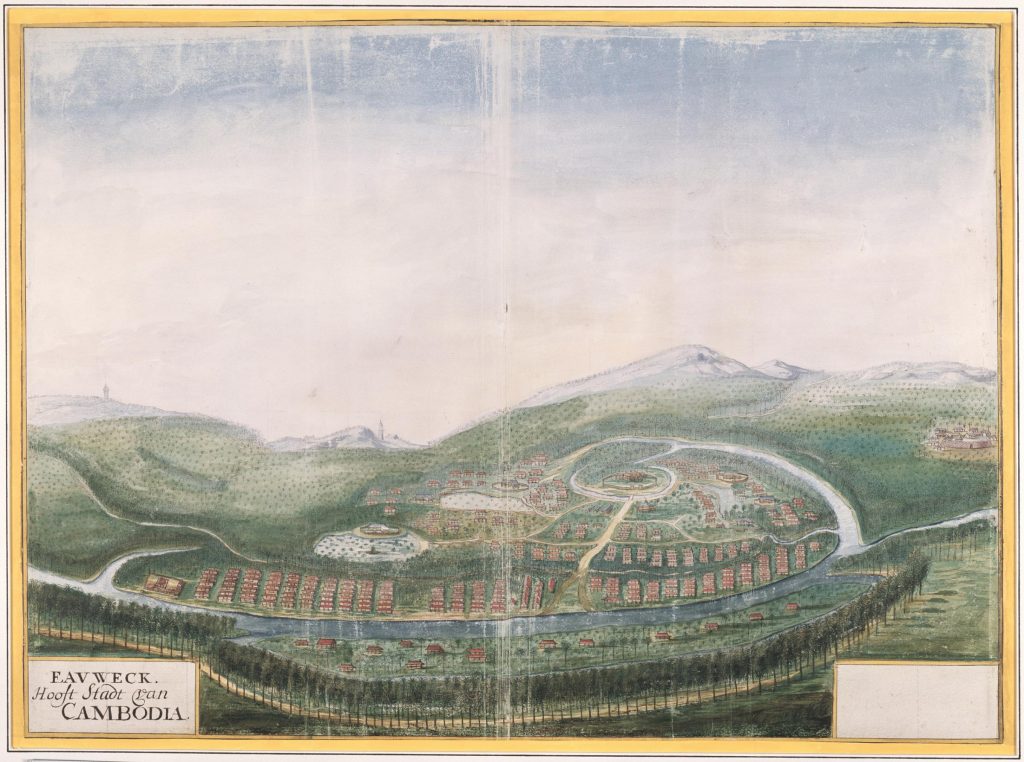

Towards the end of the 16th century, the capital of Longvek, founded around 1528 by King Ang Chan (1516–66), had grown to be a regional hub.

Situated roughly halfway between the southern tip of the Tonle Sap lake and the modern day capital of Phnom Penh, the city had welcomed international trade. Although the weakened state was not seen by foreign powers as of much use, the instability of the time was vied as somewhat of an advantage to get a foothold into more distant areas, such as gold rich Laos.

Reports from the time say that Malay and Chinese communities worked next to Japanese and Arabs, with Spanish, Portuguese, English and Dutch. Traders, pirates, mercenaries all mingled with the local population, with precious stones, ivory, incense, silks and cotton among the goods being sent away to foreign markets.

The Portuguese

The Portuguese were the first to arrive in 1511, with messengers from Admiral Afonso de Albuquerque, one of the greatest naval strategists of the age. De Alberquerque had recently taken Goa and Malacca for the Portuguese crown and followed the 3-fold strategy of spreading Christianity, combatting Islam and forging a Portuguese-Asian empire to dominate the spice trade.

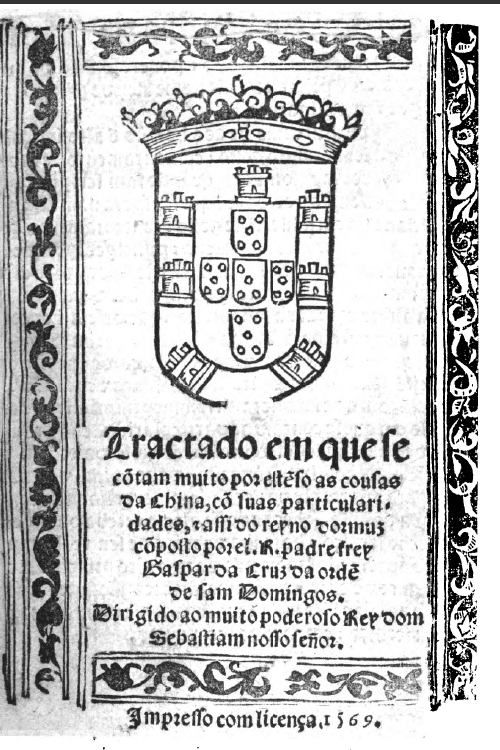

The first Christian missionary to begin work was Dominican Friar Gaspar da Cruz, who landed in 1555. The Friar, although promised that the region would be a favourable place to preach the word of God, quickly found out his work was little more than a ruse to attract more Portuguese ships. After a year the missionary gave up, according to Jesuit missionary Luís Fróis. “he wasn’t able to spread the word of God and he was seriously ill… he quickly left the region without doing much and not baptizing more than a heathen that [he left] in the grave”.

The Kings of the late 1500’s

Following the death of King Ang Chan in 1566, his second son Baraminreachea began a 10-year reign. Taking advantage of the Burmese occupation of Ayutthaya, he attacked the Thais, winning back large parts of the lost Northwestern provinces and even briefly moved the capital back to Angkor in 1570.

Baraminreachea’s son Satha I took the throne in 1576 and was either forced or coerced to abdicate in favor of his son Chey Chettha in 1584.

Sometime in this period, possibly around 1583, he had become friendly with Spanish explorer Blas Ruiz de Hernán González and his Portuguese companion Diogo Veloso. This friendship would bring about one of the most bizarre stories of the era.

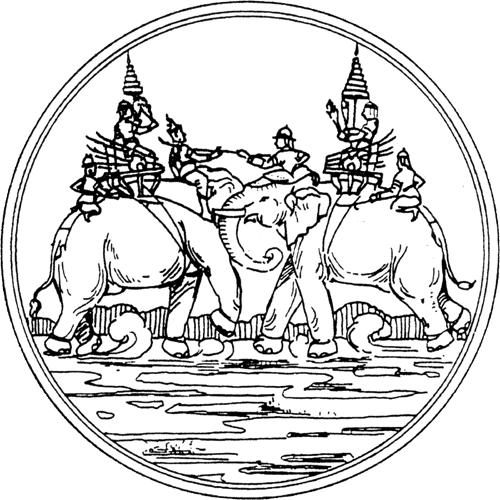

Over in the Thai Kingdom of Ayutthaya one of modern Thailand’s most revered monarchs King Naresuan (The Great) was busy fighting the Burmese. According to Thai legend, he won a duel fought on elephants against Burmese crown prince Mingyi Swa in 1593.

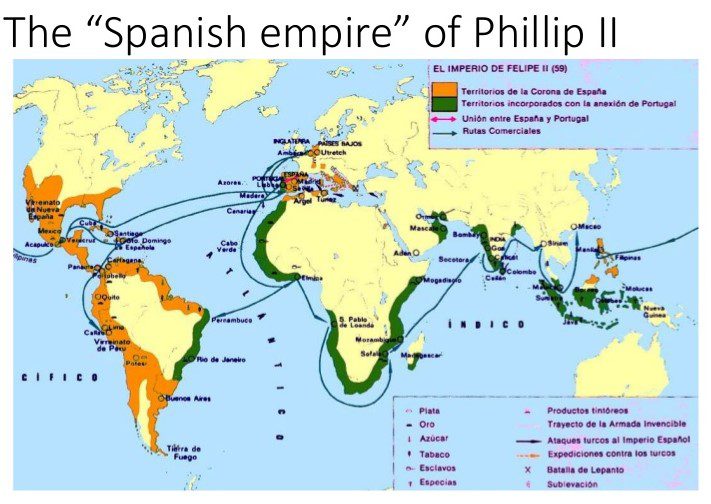

11,000 kilometers away in Europe was a man with a huge number of titles, along with a globe-stretching empire to match.

Philip II, by 1590 was King of Spain, King of Portugal, King of Naples, King of Sicily, Duke of Milan and Lord of the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands. He also had a link to the English and Irish thrones through jure uxoris as he was married to Mary Tudor I (AKA Bloody Mary) from 1584-88.

The Spanish-Portuguese Empire under Phillip stretched over every known continent, and the trade routes over every ocean. One of his legacies is the name of the massive Southeast Asian archipelago; The Republic of the Philippines.

The Spanish War

The story of the Spanish war in Cambodia begins with the son of a common Spanish farmer called Blas Ruiz de Hernán González and a Portuguese explorer Diogo Veloso. On a mission to visit Laos, they started their journey in Cambodia, where they met King Satha I and became close friends with the monarch, some sources say both Europeans married Cambodian princesses. Others say that the pair formed some sort of bodyguard unit for the monarch.

Sources vary greatly on what happened next, including the timeframe and location of the characters involved. This account joins together several contradictory pieces of information in an attempt to be as accurate as possible.

After a protracted war with the Burmese, Ayutthaya under King Naresuan began to reconquer Khmer territories around Battambang and Pursat in 1591. After being driven back, the Siamese then fought off another Burmese invasion and returned in 1593. Outflanked at Pursat, the Khmer army retreated to Babaur in Kampong Chhnang, which was then surrounded.

Cambodian Prince Soryopor, uncle of King Chey Chettha managed to fight his way out of the encirclement with 1,000 men while the rest of the defending force were killed. After reaching Longvek, Soryopor assumed direct command of the defenses as his brother had already abandoned the city. Assisted by Spanish and Portuguese mercenaries Soryopor reinforced the walls with cannon and spikes, and sent off messages for help from the Vietnamese and the Spanish governor in Manilla.

The remnants of the Cambodian navy were defeated and the invading forces converged on Longvek, beginning a siege. Siamese engineers built up earthworks higher than the city walls and began firing into Longvek. The defenders then built a second wall to shield themselves. On 3 January 1594, following an hour-long artillery preparation, Naresuan’s army stormed the city using war elephants to smash through the city gates. 90,000 Cambodians including Prince Soroypor were taken to Ayutthaya.

Some sources put Ruiz and Veloso in Vientienne at the time of the fall of Longvek. Others say that Veloso had fled to Portuguese controlled Malacca and Ruiz to Manilla during the invasion from Ayutthaya. It is generally agreed that their old friend and former king Satha was now living in exile in Laos.

The following Spanish account says that both men were captured by the Siamese, and taken into captivity.

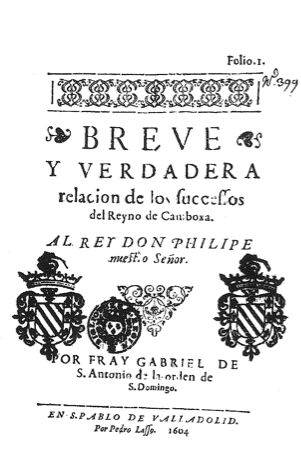

While being held on a ship destined for Ayutthaya, Blas Ruiz realized that most of the junk’s crew was made up of slaves of Chinese origin and began to stir up trouble between them and the Siamese. It ended in mutiny, in which the Chinese took up arms and killed the Siamese, taking over the cargo of the boat that, according to the Dominican chronicler Fray Gabriel Quiroga, had “five hundred arcabuces (muskets), fifty falcones, two half culebrinas, fifty jars of gunpowder, spears, catanas and gold and jewels destined to the coffers of Ayutthaya.”

Blas Ruiz, while watching the Chinese begin to kill each other over the distribution of the loot, allied himself with the other prisoners, among which there were several Japanese mercenaries. They organized a second mutiny, and the Japanese were convinced to head for Manila, where they would find refuge and reward.

Meanwhile, Diego Veloso arrived in Siam in another vessel. He managed to be released by claiming to be no more than a merchant and that his stay in Longvek was just for casual business.

Explaining himself to the king, he learned of the disappearance of the boat carrying Ruiz and the booty and, by convincing him of his skill as a sailor and his knowledge of the Spanish navigation routes, was put in charge of an expedition to search for the missing ship.

At sea they encountered a great storm that wrecked their escort. The Siamese captain gave orders to turn around, but the Portuguese convinced him to wait in a natural harbour for another day, assuring him that the storm would subside. That night, the captain, who had been in excellent health, suddenly died of a fever.

Veloso then told the crew that the last order given by the late captain was to continue in the search for the lost ship until the mission was completed. The boat then set course for Malacca, a Portuguese fortress in present-day Malaysia, where the crew were taken prisoner and the ship was seized.

Following the Siamese victory, Spanish and Portuguese who had escaped Cambodia arrived in the colony of the Philippines. There, some (supposedly including Veloso and Ruiz) were granted an audience with Governor Luis Pérez Dasmariñas, and managed to convince him that turmoil in Cambodia could easily be turned to the advantage of the Spanish crown.

With an eye on converting the region to Christianity, and opening a new route to China, 3 ships with 120 Spanish and Mexican soldiers along with Japanese and Filipino mercenaries and some missionary monks were sent to Cambodia under the command of Suarez Gallinato. The ship with Bias Ruiz was the only one that reached Cambodia. Veloso’s ship was wrecked off the Mekong delta and Gallinato was forced to reroute to Malacca due to bad weather. Veloso managed to rejoin Blas Ruiz somewhere near Chaktomuk (Phnom Penh) in March 1596.

In the meanwhile, Preah Ram I, a usurper, had seized the Cambodian throne after the royal family fled to Laos.

A Spanish account tells that the Ruiz and Veloso met with the usurper king, whom they tricked by explaining their intentions to act as impartial arbitrators in solving the problem of dynastic succession to achieve peace in the region. They also promised to subsequently establish trade relations between Spain and Cambodia.

Among others, one gift for the king presented on behalf of the governor of the Philippines was a donkey, an exotic animal of great rarity in that area of the world. The braying of the animal caused a stampede in the king’s elephant corral, causing serious damage. The king, angry at the destruction, killed the donkey and ate it that night.

Negotiations had not started well for the Iberians, and the Chinese colony of the capital, numbering around three thousand, quickly felt threatened by the Europeans and worried over their own business interests in the country.

Immediately they began to sabotage the Spanish ships and treat the soldiers with contempt and disdain, considering the newcomers as little more than barbarians. When, during a dispute playing cards, several Chinese killed two Spaniards and a Japanese in their service, the patience of Blas Ruiz, broke, causing a skirmish in the capital that ended with more than three hundred Chinese dead and the Europeans seizing all the ships in the port.

As soon as the king was alerted by the Chinese community, he demanded the return of the ships and the presence in his palace of the Spanish captains. Fearing a trap, they did not attend the meeting and, after two days camped at the city gates, they crossed into the royal residence during the night. Reduced in strength to just forty Spaniards and twenty Japanese, they set fire to the stores and burst into the royal chambers, firing their muskets and shooting the king in his chest, killing him.

Some captains then sailed back to Manilla, while Ruiz and Velloso took the best ships, recruited locals to swell their ranks, ransacked the capital of all valuables and continued with their plan to go to Laos to find the rightful king and restore him in Cambodia.

When they arrive in Laos, they were welcomed, but discovered that Satha had died of a fever. His two firstborn sons had also perished, leaving a twelve-year-old boy, Barom Reachea / Ponhea Ton as heir.

The young heir was assisted by a council of regency constituted by his stepmother, his grandmother and two of his aunts (society was matrilineal), which was seen as serious weakness by the Europeans used to their own cultural norms.

Ruiz and Veloso quickly realized that winning women’s favor would gain them more power over the child. They convinced the royal family to return to Cambodia, escorting them to the capital. The country, now decimated by fighting, accepted the coronation of the boy king, under the tutelage of his stepmother, who had also become Blas Ruiz’s lover.

The king named Blas Ruiz and Diego Velloso as governors of Ba Phnum (Prey Veng Province) and of Treang (Takéo Province) respectively under the new Spanish protectorate.

In 1598, the governor of the Philippines an expedition of two ships with two hundred soldiers and several Catholic missionaries, which the Khmer court did take well to, and soon trouble began to brew.

One of the generals of the late King who had been displaced from power by the Iberians, convinced the king to order the Spanish ships to travel up the Mekong to quell an alleged rebellion. Upon arriving in the territory, they were ambushed by an army of well-trained and well-armed Malay and Chinese mercenaries.

Ruiz tried to convince the young monarch of the betrayal that was coming. Despite his age, it was said that the boy was already fond of Spanish wine and received him drunk. His inactivity and indifference led to the annihilation of the Spanish fleet.

Veloso sent a letter to Manila asking for reinforcements, but Gallinato, whose ship had failed to reach Cambodia earlier, recommended that the governor should not send more soldiers in defense of the Spaniards, arguing that the company was not worth it and that no benefit would come from assisting them.

Governor Pérez Dasmariñas refused to send reinforcements, but authorized a group of volunteers to travel to Cambodia in a donated ship. A Dominican friar Alonso Jiménez, was also sent to Longvek with a contingent of merchants interested in the territory.

Blas Ruiz took advantage of the bad situation and went to court with a forged letter from the governor in Manila, demanding that the Cambodian king paid for services rendered to him and his men and to give a land for the construction of a fortress.

The boy king, drunk as usual, knelt crying and, apologized for having ignored the earlier advice, then authorized the construction of the fort.

The Spanish contingent were on the ground finalizing the preparations to begin the construction of the new fort when Malaysian mercenaries assaulted their camp. The boy king was also killed by rebellious Khmers.

The Spaniards fought back, and in reprisal assaulted the capital, butchering the civilian population of Malays, Chinese, Khmer, Siamese and Laotians in cosmopolitan Longvek.

Fearing the construction of a Spanish fortress, which would make the Europeans near invincible behind stone walls and artillery, a coalition of the Asian communities formed together, armed themselves and killed all the Westerners in the city, both military and religious, along with the Japanese Christian and Filipino allies.

Accounts say only one Spaniard and a handful of Filipinos survived the slaughter. The fate of Ruiz and Veloso was never discovered.

The story of these adventurers in Indochina was well known in 17th century. It is said that Cervantes took inspiration from the pair when writing Don Quixote, and the poet Gongora dedicated some verses to them.

The Spanish defeat came at a time when fortunes were beginning to turn for the empire. Phillip II died in 1598 and his son Phillip III was faced with rebellion across the colonies and closer to home.

Kaev Hua I (also known as Ponhea Nhom) ended the Spanish protectorate officially in 1600, the same year his uncle, Soryopor, who had been imprisoned by the Siamese, returned to the country with the aid of his former captors to take the throne. He succeeded in 1603 and the capital was moved to Oudong.

Cambodia had now fallen under control of the Siamese, and for the next centuries would be shifting between short reigning monarchs under the yolk of either Siam or Vietnam.

- Read about the Cambodian-Dutch War

Submitted by History Steve using various sources including Wikipedia and Daniel Garcia Valdes’ ‘Picaros Aventureros en la Corte del Imperio Jemer’

One thought on “Intrigue In Longvek- Iberians in 16th Century Cambodia”