*History Steve continues his look into the special relationship between Cham people and the Malay peninsula. Part 1 on the 1970’s-80’s refugees can be read HERE

Champa

Many of the Chams who resettled after fleeing Cambodia and Vietnam were distantly related to people in the Malay Peninsula, particularly in Kelantan state in the north east.

As a centre of learning following the spread of Islam in the area, which began around the 10th century, the Malay Peninsula became a refuge for Chams following the decline and fall of the Champa kingdom, which finally ended in 1834.

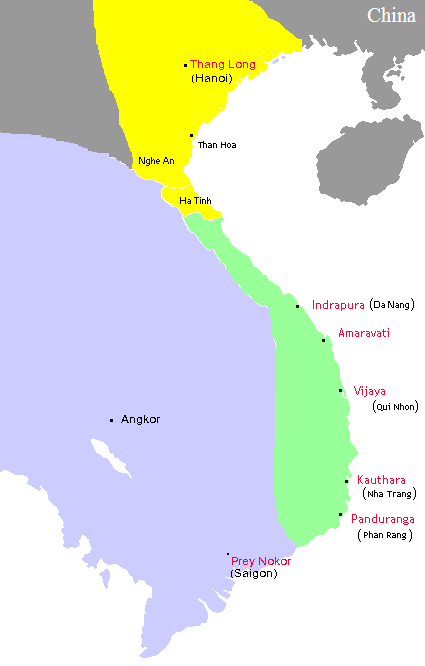

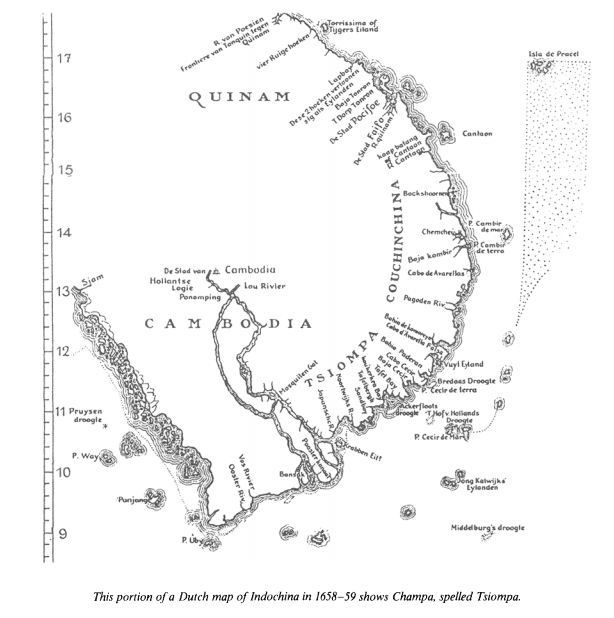

The Champa kingdom once stretched from the mountains of southern Laos along the Gulf of Tonkin towards the Mekong Delta. The people had came from the south east, most likely sailing from Borneo and Malaya during the late stone age, and were well established society by the year 200 CE. A contemporary of the pre-Angkorian kingdom of Funan, there was a still a strong connection with the sea, and with trading with both Indian and Chinese seamen was evident from at least the 4th century.

Intermittent wars between the Khmer empire and the loosely aligned Cham statelets reached their climax in 1177, when a surprise attack by a Cham naval force ransacked the city of Angkor.

Retribution came quickly, and soon Champa was beaten back and forced into an existence as a vassal state, while the Khmer empire reached its peak under Jayavarman VII.

By this time Islam had taken root and began to split the once dominant Hindu belief system, at around a similar time when Buddhism was taking hold in the court of Angkor.

A reasonable theory is that the ideas spread from eastern traders via Arabia and India since the 9th century may have appealed to those who believed massive military defeats and loss of lands meant the old gods had abandoned them. This religious divide may have made the Chma states weaker, and would prove to have lasting consequences in the final days of the kingdom. Similar theories have also been made relating to the switch of state religion in Cambodia being a factor in the decline of Angkor.

Many of the ethnic Chams living in Vietnam today still speak Cham (a Malayo-Polynesian language) and keep old Hindu traditions, while the majority of Cambodian Chams are Muslim and often learn the Arab Melayu script in religious schools.

The Decline of a Kingdom

To the north, in 938, the Dai-Viet kingdom had finally beaten 1000 years of subjugation under the Chinese and began a campaign of southern expansion. Centuries of warfare between the kingdoms culminated in a total defeat in 1471 with the sacking of the Champa main city-state of Vijaya along with the slaughter of around 60,000 of its inhabitants, with many more enslaved.

Cham society was matrilineal, and inheritance passed through the mother. Because of this, in 1499 the Vietnamese enacted a law banning marriage between Cham women and Vietnamese men, regardless of class. The Vietnamese also issued instructions in the capital to kill all Chams within the vicinity. More attacks by the Vietnamese continued and in 1693 the conquered Champa Kingdom’s territory was integrated into Vietnam.

As would happen in later centuries, many fled westward, settling in eastern Cambodia, while others crossed the Gulf of Thailand to what is now modern Malaysia and Indonesia.

A small ‘rump’ state continued to exist sandwiched between the Mekong Delta (still Cambodian controlled) and the land hungry Viet kingdom in north. This ‘Udong’ land was gradually worn down by Vietnamese encroachments. By 1832 that last part of an independent Champa was finally annexed by the Vietnamese under Emperor Minh Mach.

There were major exoduses of Cham people recorded in 1692, 1796 and 1830 – 1835 as the Vietnamese continued to push down south, with most joining their fellow exiles in Cambodia.

Resistance to Vietnamese rule continued, with several revolts in the 17th, 18th and 19th, often with assistance from rulers in Kelantan and Malacca. For example, a revolt in 1796 against Vietnamese control was led by a Malay nobleman named Tuan Phaow, who is believed to have been from Kelantan as he told his Cham followers that he was from Mecca (which is the Cham name for Kelantan).

In 1833, the Chams began a guerilla campaign, led by an Islamic clergyman from Cambodia named Katip (Khatib) Sumat who had spent many years studying Islam in Kelantan.

Cham-Vietnamese historian Po Dharma believes that personal troops of Sultan Muhamad I of Kelantan (1800– 37) sent to join the uprising, who helped raise an army to accompany Katip Sumat to Champa.

Although nominally fighting to free Champa, he used the bond of Islam to gather both Malay and Cham support and called for jihad to rally the cause from outside the country. This notion of a holy war appears to have split the Cham along religious lines, with Hindu Chams siding with the occupying armies against their kin during the uprising.

The defeat of Katip Sumat and other Malay-Cham resistance against the Vietnamese in 1834 marked the end of Champa as an entity, but Malay-Cham relations continued.

Following the uprising, the Vietnamese began a systematic oppression of Cham people, which on came to an end in the 1860’s with French colonization of Cochinchine.

The Missionaries

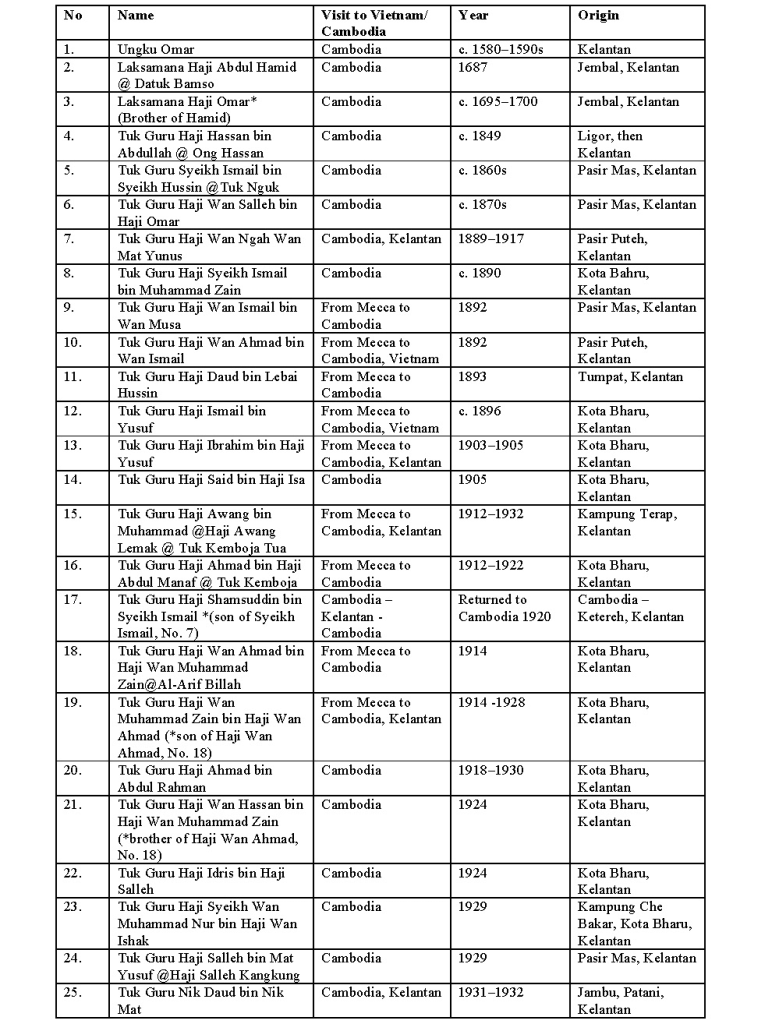

Islamic missionaries from Kelantan had been visiting the displaced people in both Cambodia and Vietnam since at least the 16th century. A scholar named Ungku Omar was recorded as visiting the communities in Cambodia during the 1580’s and 1590’s. At this time there were also sizeable ethnic populations of Malays based in the post-Angkor kingdom, so it would be easy to suppose an amount of interaction between the closely related groups taking place, including intermarriage.

Although the names of countless preachers and missionaries have been forgotten over time, their place of origin, namely Kelantan and the Malay Peninsula, was certainly remembered by generations of Chams. It was reported that, when Malaya broke away from the British Empire in 1957, the act was celebrated among the Cambodian Chams as “Kelantan is now independent!”

Many Chams sent their children to Kelantan for religious education, with Pattani in Thailand also being a popular destination.

Husin bin Yunus, a native of Kampong Cham, was sent by his parents to study religious teachings at Kampung Pulai Chondong, Kota Bahru, Kelantan in 1957. He continued his studies and returned to Cambodia in 1964 and became a religious teacher.

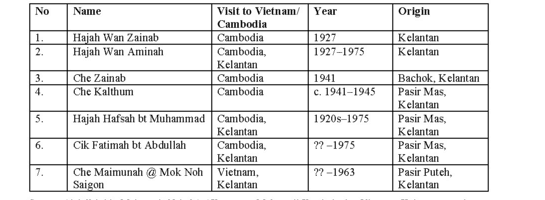

By 1971, life was becoming increasingly unbearable in Cambodia,so decided go back to Kelantan with his family. Husin bin Yunus’ research on the historical links between Kelantan and the Cham people provided a list of several Muslim missionaries, both male and female, going back to Ungku Omar in the late 16th century. At least three female missionaries returned to Cambodia in 1975, their fate is unknown.

Language Links

Today in Kelatan there are still linguistic hints of a shared history. Place names in Kelatan such as Pengkalan Chepa (Base of the Chams) and Kampung Chepa (Village of the Chams), along with fabric and materials, sutra Chepa (Cham silk), kain Chepa (Cham cloth), padi Chepa (Cham rice) among others.

Local legend says Kampung Laut Mosque, one of the oldest in the country with the current structure dating back to the 18th century, was originally built by Cham sailors on the site in the 15th century.

Sadly, the same cannot be said for the place that was Champa. Years of ‘Vietnamization’ following the conquest of the kingdom all but obliterated original place names. Historical sites such as Mỹ Sơn, a Hindu temple complex which once would have rivaled Angkor, were heavily bombed during the Vietnam War.

Chams Today

The majority of the modern day Cham population resides in Cambodia, even after suffering horrendous loss of life under the Khmer Rouge regime, where it is estimated to be around 300,000. Numbers for Vietnam are disputed, but probably around 200,000.

In Malaysia, most of the pre-refugee Chams have long been assimilated into the wider Malay community through marriage. One estimate puts the number of ‘Khmer-Islam’ descendants of the almost 10,000 refugees granted asylum in the 1980’s has grown to around 50,000.

However, in Malaysia there are also undocumented communities, of those who have entered unofficially, or overstayed following visits to family. This group lives on the fringes of Malaysian society, often in abject poverty. This was highlighted in Pekan in February 2019 when the body of Siti Masitah was discovered, Born to undocumented parents who moved from Kampong Cham in the 1990’s, she had a Malaysian birth certificate, but was listed as a non-national. Cambodian Mohd Amirul Abdullah, 23, was later charged with her murder, and questions were raised in the country about the sizable, but insular community.

Submitted by History Steve

Sources include: Wikipedia, D Wong Tze-Ken, Jean-Michel Filippi, Po Dharma, Abdullah bin Mohamed

.