2019 has so far been a bad year for deaths and injuries caused by munitions left over from the series of wars that ravaged Cambodia from the 1960’s through to the 1990’s. Chinese, American, Russian, British, French- the cold war powers dropped or supplied these in the millions to a small war-torn country with a total population at the time less than that of New York.

The causes of these casualties vary dramatically; from unlucky farming accidents, illegal poaching, fires detonating buried shells, children playing with discarded grenades to unauthorized mine-clearers working for private companies and civilians attempting to remove explosives to make crude fishing bombs.

At least 30 cases were reported for the period between January and mid-March 2019, which is almost double that of the previous year.

As land prices and demand increases, former battle fields and areas of ‘no-man’s land’, especially around the Thai border have become profitable, but risky. Meanwhile, economic pressures and depleting stocks are forcing those who have traditionally relied on fishing to make a living.

Priorities

Mine clearance really began under UNTAC. Cambodina Mine Action Center (CMAC), was founded from the UNTAC Engineering components, which utilized demobilized soldiers.

For many years resettlement land was the main priority for landmine clearance. As the Thai border camps closed, 320,000 returnees had to be put somewhere. A disproportionate number of those returning were from Battambang, Banteay Meanchey and Oddar Meanchey, which were also the most heavily mined regions. To be resettled in relative safety, designated areas were focused on and cleared first.

Following the resettlement program, the next priority was “casualty reduction”. By this time there were 3 agencies; CMAC, MAG and HALO. These groups, using available statistics, focused on the communes and districts which were suffering the highest number of deaths and injuries from UXOs. Thanks to these efforts, the casualty rate dropped significantly.

The third phase was clearance for humanitarian relief and development. Land that had once been used for agriculture, but became contaminated, was needed to boost food production. Land for new infrastructure, civil and economic, needed to be made safe. Roads were also important, with new ones such as from Samroang to Anlong Veng being built.

Above all, population pressure in central Cambodia was growing in provinces like Kandal and Kampong Cham. The north and northwest were still relatively underpopulated, so in the early 1990’s Social Land Concessions were granted, and these areas needed to be made safer.

These SLC’s were done in a simple way; go north, clear some jungle, and develop the land, although there were limits on the size people could claim. Essentially it meant people were moving up into dangerous areas to forge a new life on reclaimed land.

These newcomers became by far the largest group of victims in disproportionate numbers. Most local people were already aware of exactly where the mines were. They had had livestock or fellow villagers blown up in certain areas and knew to keep away from these zones. Some had either laid the mines themselves as soldiers or militia during the conflict, or had knowledge of them being laid at the time by other members of the community.

The Legacy

This is still continuing today with an expansion into land that was once forest, or even onto land that was once worked, but has been fallow for decades due to contamination.

For example, a former humanitarian worker remembers spending time in a community at the edge of the K5 belt in Preah Vihear, near the Thai border. He recalls the location of the mine belt was “blindingly obvious”.

“You could see the end of the rice paddies, grassed over during the growing season, end abruptly and edged by 4 to 5 foot high grass on what was flat and looked like the same ground the paddies were on”.

He continued

“On investigation, it turned out they knew exactly the extent of the mine fields. But every few years would risk extending the land by one more furrow to gain an extra bit of land, which sometimes would end a in a detonation.”

A surprisingly large amount of agricultural land in was, and still is in disuse due to contamination of landmines. With growing pressure for fertile soil, many people take the risk, often clearing it themselves, or with contracted labour.

Land which was once confirmed, or at least suspected of being contaminated is declared “”clear”” and taken off the work plans if it has been worked on for three consecutive years without an incident. This allows the mine agencies to concentrate on more dangerous spots, but also comes with a risk to the farmers.

While landmines can and do remain dangerous for decades, many deteriorate to the point of malfunction. The wooden “box mines” simply break down after years in wet ground. Others have components that will last a hundreds of years, but the rubber which encases the top will actually perish, a good example of that is the PMN series, Bakelite or plastic bodies, the top of which is sealed with a heavy rubber face. As the rubber perishes, the water and dirt invade the mine, it can often fail.

A combination of efforts from the clearance groups, and the natural life of these weapons have seen a dramatic decrease in deaths and injuries over the past few years.

Explosive Remnants of War (ERW’s) are another problem. These include mortars, grenades and ammunition. Between 2017- 2018 they made up 70% of all deaths and injuries in Cambodia.

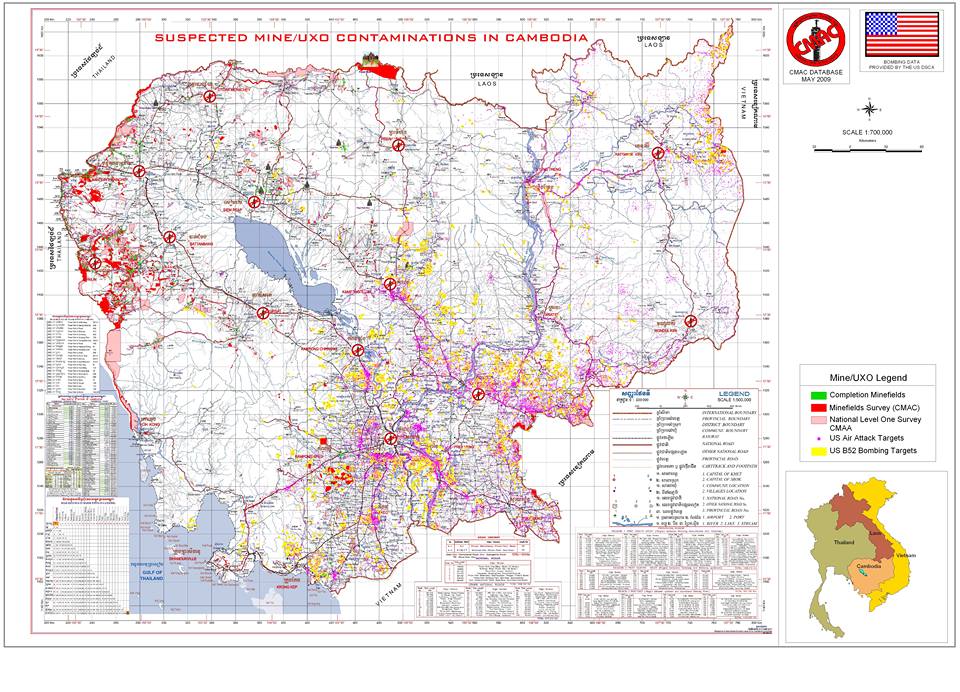

2,756,941 tons of bombs were dropped across Cambodia by the USAF during the Indochinese wars between 1964-75, in 230,516 sorties on 113,716 sites. Just over 10 percent of this bombing was indiscriminate, with 3,580 of the sites listed as having “unknown” targets and another 8,238 sites having no target listed at all.

Countless bombs, grenades, mortars and artillery shells have more random locations, either failing to detonate at the time, or being hidden in secret arms caches during the fighting.

Although relatively stable when undisturbed, they are extremely volatile when heated. As more forest and scrub is cleared by slash and burn techniques, accidents are inevitable. Artillery shells in particular appear to be a favourite source of illicit explosives, which are extracted once a piece has been defused.

With socio-economic pressure mounting, and the pace of development pushing land clearance further and deeper into former battlegrounds, it seems as if deaths and injuries may continue well into the foreseeable future.

Fortunately, the casualty rates drop in the rainy season, as work in more remote areas is forced to slow down. But there is still much work to be done, at a not inconsiderable expense, if Cambodia is to achieve mine free status by 2025.

Submitted to CNE by writer A.N. Onymous

3 thoughts on “UXO’s – A Brief History”