“To Liberate the Oppressed” – US Special Forces Motto

For America, the Vietnam War was unlike any other war it had fought before. It was a complicated conflict which lasted over 40 years.

America was involved in the last nine years of the war and the end involved the humiliating mass evacuation of American personnel out of the country in 1973.

It is estimated that over the course of the war, American forces casualties amounted to some 58,000 dead and over 300,000 wounded, as well as losing nearly 10,000 aircraft and helicopters.

It was, at times, a highly unconventional war with few set battles and a sporadic but intense aerial campaign.

Despite the introduction of high tech weapons like SAMs (Surface to Air Missiles), dedicated gunships, and the widespread use of guided munitions, it was still a down and dirty war. The need for Special Forces had never been greater.

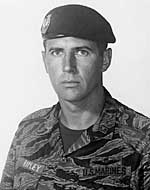

Many exceptional and brave men served in Vietnam such as Gunnery Sergeant Carlos Hathcock, Captain John ‘Rip’ Ripley, Sergeant Ed Eaton, and Captain John McCain. Among these gallant heroes was Jerry “Mad Dog” Shriver of the US 5th Special Forces.

He was born on September 24, 1941, in De Funiak Springs, a small resort town in Florida. Little is known about Shriver’s childhood and his story starts when he joined the Army at a young age.

He arrived in Vietnam in 1966, having risen to the rank of Sergeant First Class. He ended up leading a platoon in the 5th Special Forces with MACV-SOG (Military Assistance Command, Vietnam Studies and Observation Group) who were an unconventional task force assigned to carry out top-secret missions throughout the South-East Asian theatre during the Vietnam war.

The team’s main role was to perform deep penetration missions behind enemy lines and then carry out very hazardous strategic reconnaissance and interdiction duties.

A lot of what Shriver did with MACV-SOG may never be known as they were highly classified missions, often in countries that they should not have been in. But the decorations he was awarded were a reflection of his bravery and dedication to his duty and achievements.

He received two silver medals, three Army Commendation Medals for Valor, Seven Bronze Stars, One Purple Star, One Air Medal, and the Soldier’s Medal during his short life.

Such was his reputation that “Hanoi Hanna” gave him his nickname of “Mad Dog” and the North Vietnamese government seemed so afraid of him that they even offered a bounty of $10,000 (equivalent to $70,000 in 2018) if someone was to kill him.

Medal of Honour winner, Lieutenant Jim Flemming, who had served with Shriver on several missions, summed him up as “The quintessential warrior loner.”

It was said that by his third tour of duty Shriver had become troubled and anti-social. He had even started to drink heavily and was said to be having trouble sleeping. It was even said he slept with his M3A1 (Grease Gun) Suppressed Sub-machine Gun under his pillow.

But most people who served with him acknowledged that he was also a brave, dedicated, and committed soldier, who would do anything to help his team.

In 1969, Cambodia was increasingly becoming a base of operation for units of the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN). The logistical elements of the 7th PAVN Infantry Division were based in one such area of south-east Cambodia known as ‘The Fish-hook’ in the Kampong Cham Province.

The Fish-hook was of particular importance to the PAVN as it was only 50 miles (just over 80 kilometers) from Saigon and there was a rumor that the base was one of the major Viet-Cong political and military headquarters. This was later proven to be false.

The American Military felt so threatened by this development that on March 18, 1969, the PAVN base at Fish-hook was targeted by a large number of giant B-52 Stratofortress bombers. Then on April 24, 1969, the B-52s carried out two more sorties: the first at midnight followed by a second one at 04:00 am.

Later on that morning, Shriver’s hatchet platoon was tasked with carrying out post-strike surveillance of the bombed site using four helicopters.

As Shriver boarded the Huey helicopter at Quan Loi on that fateful day, he asked a colleague to “Take care of my boy.” Shriver was referring to Klaus, his beloved German shepherd. His first dog, Adolf, had escaped from the camp and been eaten by the locals. No doubt he was worried this could happen again.

Shriver was famous for carrying into battle as much weaponry as humanly possible. That day he was said to be carrying a .38 revolver, a .45 automatic, a 9mm UZI sub-machine gun, and had a large scuba diving knife strapped to his leg. He was also known to carry a .357 magnum at times.

The mission went wrong almost immediately. Shortly after they had landed, they came under machine gun fire from heavily fortified PAVN positions. Shriver estimated his one platoon was facing between three to six platoons of North Vietnamese soldiers in a series of bunkers and trenches.

Shriver moved forward with a South Vietnamese soldier to assess the situation. He entered a tree line as he moved up.

That was the last time he or the accompanying soldier were seen. Shriver did keep in contact for sometime afterward, but he would appear to be injured several times before the transmission finally ceased.

Meanwhile, the fire-fight raged on, and the American platoon found themselves pinned down and taking heavy casualties. Helicopter gunships and A1E Skyraiders came to their assistance, but the situation was so dire that the platoon requested immediate extraction.

After seven hours of fighting, the US helicopters were able to get in and evacuate the American survivors. This whole episode was seen as an unforeseen disaster. Of the 18 members of Hatchet platoon, two were confirmed dead, ten were wounded and six, including Shriver, were listed as MIA.

Hanoi Hanna was heard later that day to boast that they had captured Mad Dog Shriver. In another radio broadcast, Hanoi Hanna claimed they had Shriver’s ears, which was thought to imply that he was now dead and they had his body.

On May 1, 1970, the Fish-hook area was attacked by the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) supported by an American Taskforce.

No trace of any important enemy command structure was ever found there. But it was still a significant victory for the Americans as they found and neutralized a large logistics base with nearly 200 storage bunkers containing over 1,200 individual weapons, around 200 crew-served weapons, 30 tons of rice, and vast amounts of ammunition and explosives.

On the 12th of June 1970, a team from the US Grave Registration Unit arrived at the battle-site to search for seven soldiers who had gone missing during the battle, including Shriver. Although they did recover two bodies, neither of them were Shriver’s. In fact, no trace of him or his equipment was ever found.

Shriver was less than three weeks away from finishing his third tour of duty. He was just 27 years old when he was officially listed as MIA (Missing In Action).

In 1974, the then Secretary of the Army gave Shriver a ‘Presumptive Finding of Death,’ and his file permanently was closed.

Shriver’s name is forever immortalized at ‘The Wall’ (The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C.) at Panel 26W, Row 41.

Really enjoyed the story. It was mentioned that not much was known about Sgt. Shriver’s childhood’ did Sgt. Shriver have any known family that were contacted and notified of his MIA status? Would like to know more.

Afraid we don’t have any knowledge of this.