PEKAN: HAS the brutal murder of 11-year-old Siti Masitah Ibrahim, whose decomposed body was found near some bushes in Tanjung Medang Kemahang here last weekend, opened a can of worms on the presence of several villages occupied by refugees from Cambodia?

At least four settlements — Kampung Pulau Keladi, Kampung Tanjung Agas, Kampung Sekukuh and Kampung Kemahang — in Tanjung Medang Kemahang, where the killing occurred, are occupied by the descendants of Champa from Cambodia.

The majority of villagers here are Cham Muslims who escaped from Khmer Rouge atrocities in Cambodia in the 1970s and ended up in Malaysia, with some choosing Pahang to start a new life with refugee status.

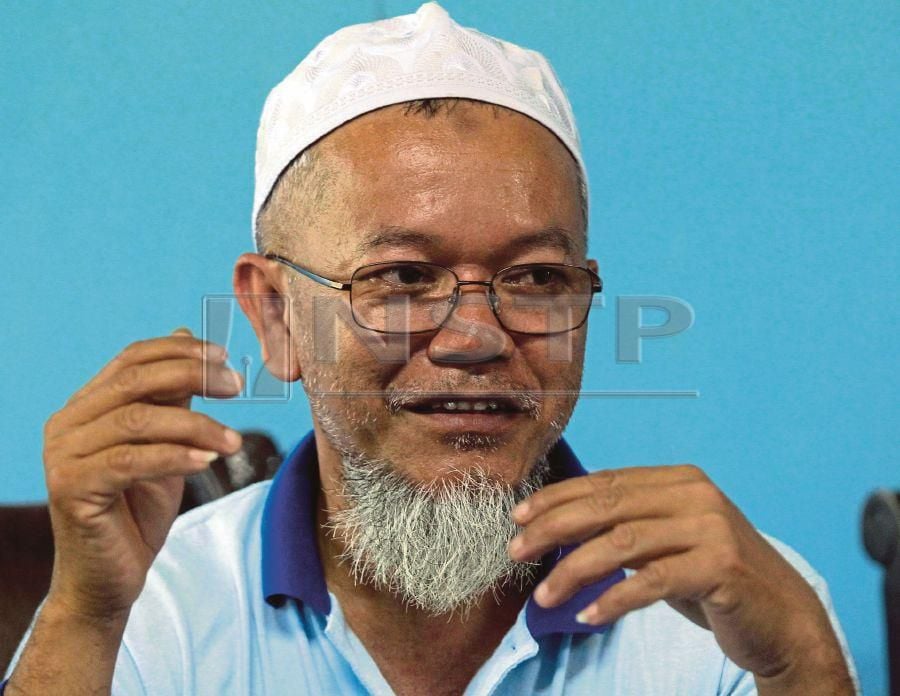

Abdul Fasir Omar

Kampung Kemahang Cambodian community representative Abdul Fasir Omar said the village had around 300 people and the majority of them did not have identification documents, while some possessed United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees cards, red identity cards and working permits (to live in Malaysia).

The 51-year-old said while the elderly villagers did not have identification documents, some of the younger generation, those born in Malaysia, owned MyKad.

“Those living here are known as Champa Muslims or Cham Muslims who fled Cambodia in the late 1970s. Many ended up here as refugees. I came to Malaysia as a refugee in 1985 and lived in Kajang, Selangor.

“The first generation of Champa Muslims arrived in Kampung Kemahang in 1995 before I moved here seven years later. When I came here, there were around 10 families.

“More people started moving in 10 years ago. Now, there are about 300 people from 80 families living here.”

Fasir said many of the villagers had applied for permanent resident status, but were rejected by the government on several occasions.

“I have a red identity card and my application for PR status has been rejected three times. Now I am making a fourth attempt.

“The lack of proper documentation has deprived our children the opportunity to get formal education in school.

“Most of us here work as cage fish farmers and do odd jobs, and we have never caused any trouble.

“The recent murder incident (involving Siti Masitah) does not define the Champa Muslims. The incident was caused by one individual and the entire community should not be punished (or portrayed as bad people).”

Fasir, who has 10 grandchildren who were born in Malaysia, said he and his fellow villagers had no plans to return to Cambodia and hoped the government could assist them in obtaining identification documents.

On the government’s policy to allow stateless and undocumented children to attend school starting this year, Fasir said the school required identification documents from the parents before their child could attend lessons.

“We built a religious school called Madrasah Islamiah 10 years ago to provide religious lessons to children. Some parents even send their children to religious schools in other districts.

“Our concern is the future of the Champa Muslim children as without education, they will not be able to do anything other than living in the village and continue doing odd jobs when they grow older. We hope the authorities can help.”

Last year, it was reported that Pahang had about 10,000 people from the Champa community with most of them living in Kuantan and Pekan, and working either as fishermen and farmers, and doing odd jobs.

Siti Masitah’s parents — Ibrahim Ali, 39, and Solihah Abdullah, 35, — along with the 23-year-old suspect who is now remanded at the Pekan police headquarters, do not have identification documents or permanent residence cards.

The girl’s body was found in a badly decomposed state in an oil palm plantation at Kampung Tanjung Medang Hilir. She had gone missing on Jan 30.

Most villagers in Kampung Kemahang work as cage fish farmers. PIX MUHD ASYRAF SAWAL

Perkim: Increase in membership applications from Cambodians

The Pahang chapter of the Malaysia Muslim Welfare Organisation (Perkim) has recorded an increase in new membership applications from Cambodians, including those from the Champa Muslim community living here.

Its secretary, Mahadi Deraman, said some of them used the non-governmental organisation’s card as an identification document. He said many of the Champa Muslims living here as refugees assumed the membership card was an identification document authorised by the government.

“It is a Perkim membership card and not an identification document as they think. Some of them claim that the membership cards are helpful when they are out fishing at sea or doing odd jobs in nearby villages, especially when the authorities ask for their identification documents.

“Muslim foreigners can become Perkim affiliate members. We assist them in terms of welfare and education to ensure they live a normal life and are independent.”

Mahadi Deraman

Mahadi said Champa Muslims entered Malaysia as refugees following a crisis in their country and the Cherating refugee camp was set up to provide shelter.

He said the camp, equipped with a clinic and school, was closed after 10 years and the refugees moved to other parts of the country. Some remained in Kuantan while others moved to Pekan.

“Some question why they (Muslim Cambodians) did not return to their country after the turmoil ended and instead their numbers have been increasing over the years. The government should look into their needs with the assistance of NGOs and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

“This includes healthcare and education. Many of the stateless children and their parents are not aware that they have access to formal education in government schools.”

Mahadi said some of them had lived in Malaysia for 20 to 30 years but had yet to obtain identification documents.

“Some members seek Perkim’s assistance to secure citizenship status, but it is not a simple process. However, their children have MyKad and even birth certificates.”

Bebar assemblyman Datuk Fakhruddin Mohd Ariff said he was aware of the presence of the Champa Muslim community in his constituency.

He said the pioneer batch living here comprised refugees who fled Cambodia following a conflict in the 1970s.

“Those living in Pulau Keladi have red identity cards, but many of those who arrived much later do not have proper documents.”