Early on Christmas day, 1978, while many in the Western world were at midnight mass, or hanging up stockings, a massive invasion force which had been secretly assembled crossed over the Cambodian-Vietnamese border.

Within weeks Phnom Penh was under new leadership and the forces of Pol Pot melted into the jungles and across the Thai border. The event is still controversial- with some seeing a humanitarian gesture to rid the country of the Khmer Rouge, while others claim a plan of Vietnamese (especially Hanoi based North Vietnamese) plan for hegemony over the whole area of what was once French Indochina.

The fall of Saigon by North Vietnamese forces on April 30, 1975, was preceded two weeks earlier by another Communist victory: the capture of Phnom Penh to the Khmer Rouge.

Yet less than four years later, Vietnamese troops would engage in a second conquest—this time targeting its erstwhile allies, using many of the tanks and aircraft it captured from South Vietnam.

The invasion brought an end to the Khmer Rouge’s monstrous genocide, but not to the war itself. The Khmer Rouge waged a bloody guerilla resistance war against the Vietnamese and their Cambodian allies, assisted by two more Western-aligned resistance group.

The Khmer people of Cambodia have ethnic ties to southern Asia and practice a hybrid Buddhist-Hindu faith. Just as the Vietnamese historically resisted imperial occupation by China, the Khmer historically were subject to foreign encroachment from Vietnam.

The Khmer Rouge had been formed by a clique of Marxist students educated in Paris in the 1950s and 1960s, adopting a uniquely extreme ideology combining fervent Khmer nationalism with Maoist-style communism, which emphasizes revolution by the rural peasantry rather than an urbanized working class.

However, the Khmer began with only limited domestic support in Cambodia. Their conquest of Phnom Penh was only possible with aid from North Vietnam, which armed and organized the Khmer Rouge to so it could infiltrate its forces through Eastern Cambodia with less interference from the politically-divided Cambodian government. A massive bombing campaign by U.S. warplanes devastated rural Cambodia, delaying but failing to prevent a Communist victory, and may have increased pro-Communist sentiment amongst the peasantry.

The ruling clique renamed their country the Democratic Republic of Kampuchea and implemented a spectacularly self-destructive and brutal police state unlike any other Communist regime. Not merely content to promote rural interests, the Khmer forced Cambodian city-dwellers from their homes, emptying the cities so that urbanites could live an ‘authentic’ life in the countryside. The regime implemented Chinese Great Leap-style agricultural policies that predictably led hundreds of thousands to die from famine.

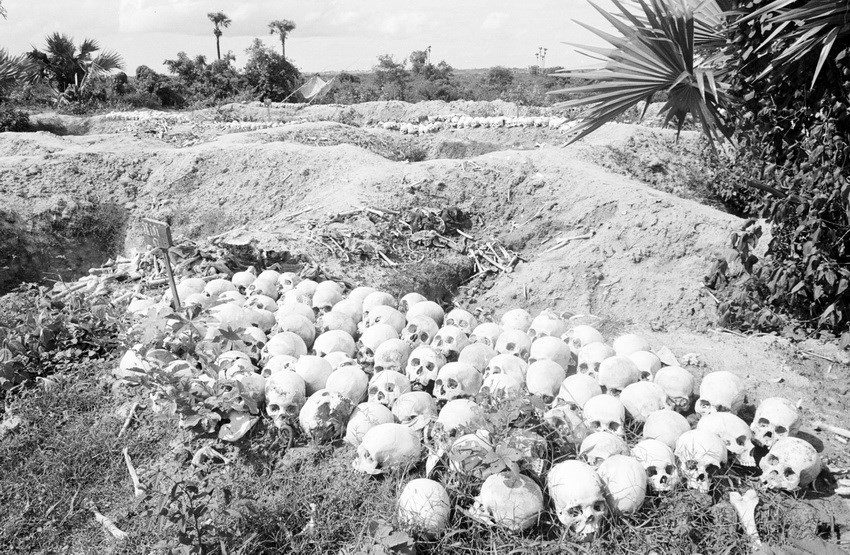

Hundreds of thousands more Cambodians suspected of political disloyalty or “immorality” were murdered in the infamous Killing Fields. Even adult victims’ children and babies were killed, smashed to death against tree trunks to save bullets. Xenophobic and obsessed with Khmer racial purity, the Khmer Rouge also targeted minorities and people of mixed descent. In four years of rule, these genocidal follies killed between 1.5 to 3 million people in a country of only 8 million.

The Khmer Rouge’s ultra-nationalism made them violently suspicious of the Vietnamese Communists, even though the Khmer Rouge’s conquest of Cambodia had only been possible with Hanoi’s support. As early 1974, the Khmer Rouge began purging Vietnamese-trained members from its ranks and skirmishing with Vietnamese troops. Increasingly, the Cambodian Communists turned to China for support, which furnished Kampuchea with economic and military aid.

Still, Communist Cambodia and Vietnam remained officially friends at first, and continued diplomatic outreach even while their troops clashed violently over border towns and outlying islands. But the Khmer Rouge felt that Vietnamese border towns as belonging historically into the Khmer—and it asserted its claims with habitual violence, dispatching troops on cross-border raids that massacred thousands of Vietnamese civilians.

Hanoi finally responded to the attacks in December 1977 with a punitive multi-division invasion supported by air power. However, though the Khmer Rouge’s forces were steam-rolled in combat, the Khmer to escalate hostilities even further with more cross brutal cross-border raids, peaking with the merciless slaughter of 3,157 villagers at Ba Chúc in April 1978, leaving only two survivors.

Hanoi then tried to unseat the Khmer Rouge regime using its own Maoist ‘People’s War’ doctrine, by organizing a rural insurrection amongst sympathetic elements of the population. Ironically, the Maoist doctrine proved unsuccessful in the face of the zealousness of the Khmer Rouge’s secret police, which learned of the subversive elements and crushed them.

By this point, the conflict increasingly was drawn into the dysfunctional relations between Communist states. Beijing wanted to cultivate Cambodia as an outpost of its influence. Vietnam, seeking to keep the Chinese out, signed a treaty of friendship with the Soviet Union, which by then was possibly on worse terms with Beijing than with Washington, securing the military and political support for a Cambodian invasion.

The Vietnamese Army assembled 150,000 troops in thirteen divisions on the Cambodian border. It could draw upon a pool of 900 tanks—a mix of T-54 and Type 59 medium tanks, PT-76 and Type 63 amphibious tanks, and captured U.S. M41 Walker Bulldogs. It’s Air Force counted over 300 warplanes including squadrons of A-37 Dragonfly attack jets and F-5 Freedom fighters captured from South Vietnam, as well as older Soviet MiG-21 and MiG-19 jets and beefy new Mi-24A Hind armored attack helicopters. These were vectored to targets by observers in slow Cessna UH-17 and O-1 utility planes. In addition, the Vietnamese organized three regiments (15,000 men) of Cambodian fighters that would form of the nucleus of a new Cambodian government.

The Kampuchean Revolutionary Army mustered only seventy thousand troops and far fewer tanks. Its fledgling Air Force retained some twenty abandoned Huey helicopters and twenty-two T-28 Trojans trainers, and sixteen Shenyang J-6 fighters (MiG-19 clones) received from China, which also dispatched thousands of advisors.

Vietnamese troops began a limited invasion of north-eastern Cambodia on December 21, 1978, then four days later launched the main offensive on three axes in the southeast, converging on the capital of Pnomh Penh. The Vietnamese advanced blitzkrieg-style, using armored columns supported by airpower to “fix” enemies in place, and then having the reinforcement waves bypass identified enemy positions to sustain the advance and cut enemy lines of supply. Regional capitals Kracheh and Stung Treng were captured in five days, then the port in Kampot seized by an amphibious landing.

The Khmer Rouge regime tried tackling the Vietnamese attacks head-on, but its starving and demoralized troops failed to mount an effective resistance. After just two weeks of fighting, Pol Pot’s clique ordered its troops to melt into the jungle to wage a guerilla resistance war and fled Phnom Penh in five Huey helicopters—only narrowly dodging a Vietnamese air strike.

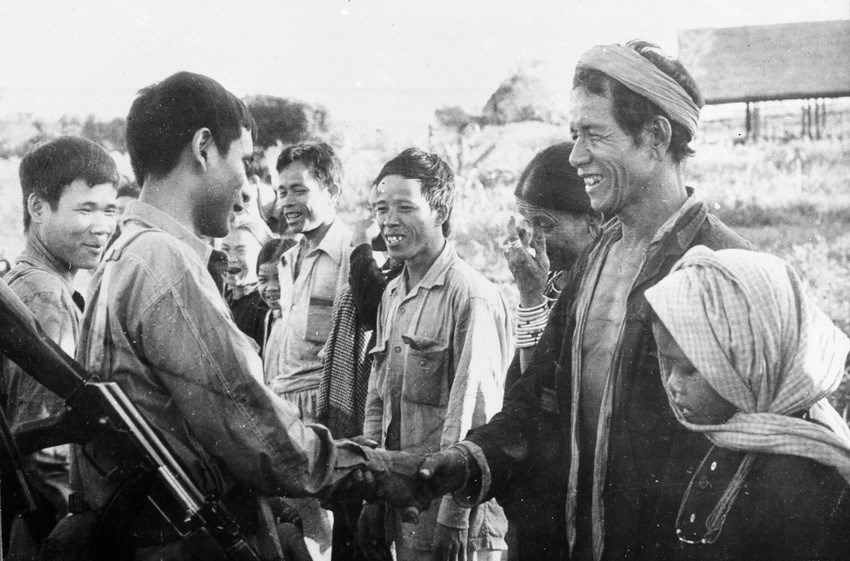

On January 7, Vietnamese tanks rolled into Phnom Penh, linking up with commandos earlier landed by helicopter, and installed a new government under Hun Sen, a former Khmer Rouge battalion commander. The Khmer Rouge’s navy was sunk nine days later by the Vietnamese Navy in a bloody battle that saw twenty-two ships sunk.

China, infuriated by the overthrow of its client-state, launched a punitive invasion of mountainous Northern Vietnam on February 17. However, the People’s Liberation Army’s inexperienced troops and tanks sustained heavy losses from the defending Vietnamese. The invasion failed to divert Vietnamese troops from Cambodia, and a ceasefire was declared after a month.

Hanoi found to its surprise that it had become internationally ostracized for the invasion. Isolated from international aid, Vietnam suffered economically and became closely dependent on the Soviet Union. Many Khmer, for their part, saw the Vietnamese intervention as vindicating the Khmer Rouge’s worst fears of Hanoi’s imperial designs on Cambodia.

Throughout the 1980s, the United States, smarting over its defeat in Vietnam, collaborated with Thailand and China to funnel arms and support to resistance armies, some of which wound up in Khmer Rouge hands. The Vietnamese army ironically found itself on the other side of a brutal counterinsurgency war not unlike the one it had waged against the U.S. forces during the 1960s and 1970s.

The decades-long war finally wound to its end in the 1990s, with a Vietnamese withdrawal, deployment of a UN peacekeepers and the disbanding of the Khmer Rouge. The Hun Sen regime managed to subvert provisions for democratic elections, however, and remains in power to this day, now again courting Chinese support.

Vietnam’s invasion brought an end to a horrifying genocide. Furthermore, Hanoi can hardly be faulted for using force after foreign troops repeatedly invaded its territory and massacred thousands of its civilians.

However, Vietnamese generals and politicians have made clear the invasion was meant to serve Vietnam’s interests in expelling Chinese influence over Cambodia, not a humanitarian mercy mission. For some Khmer, the Vietnamese were seen as yet another foreign invader.

Thus the tragic conflict defies the natural desire to define the war in terms of black-and-white morality.

Sébastien Roblin holds a master’s degree in conflict resolution from Georgetown University and served as a university instructor for the Peace Corps in China. He has also worked in education, editing, and refugee resettlement in France and the United States. He currently writes on security and military history for War Is Boring.

The original story was published by Sebastien Roblin in National Interest Magazine:

Photos: VNPLUS

Full documentary:

Another great article. Well written and informative.

This article is very well written and factual. I lived in Cambodia from 2002 to 2017. Only after reading various books did I learn about the entire situation in Cambodia from the ascendancy of Sihanouk to the 1970 coup, civil war, Democratic Kampuchea and Pol Pot, UNTAC era to the present I had never heard about the attack on Vietnam by the Chinese in 1979. Most people are also not aware that the US and China, both members of the UN Security Counsel, supported keeping the Khmer Rouge as the official UN representative of Cambodia after the Vietnam Army and Hun Sen established the new government in 1979. Today relations between Vietnam and Cambodia are again changing as Hun Sen is establishing closer economic and strategic ties with China, the former supporter of the Khmer Rouge Regime in the 1970’s. The political history of Cambodia is one of the most complex and is full of strange events, tragedy and interesting personalities.

Sorry you left out the part played by Sihanouk in the rise of the Khmer Rouge after the diletante King was overthrown by the corrupt Lon Nol and threw his support behind the Khmer Rouge, giving them credibility amongst the Cambodian peasantry. I believe this is amongst the most important aspects of the rise of the Khmer Rouge.

Sorry, but this has been dealt with in several other articles. Do you expect the entire history of Cambodia 1940-1990 to be summarized in 1000 words? Check some other articles by searching ‘history steve’ in the search box.