Youk Chhang receives the Ramon Magsaysay Award 2018

for his work gathering and preserving evidence of the Khmer Rouge abuses

TEXT BY CAMILLE ELEMIA

PHOTO BY MARIA TAN

https:///world/regions/asia-pacific/210772-profile-ramon-magsaysay-awardee-2018-youk-chhang-cambodia

MANILA, Philippines (rappler.com) – It was full circle for 57-year-old Youk Chhang, who in 1986 sought refuge in Bataan, Philippines, after surviving the brutal Khmer Rouge regime that killed nearly two million Cambodians from 1975 to 1979.

More than 3 decades later, Chhang returned to the country he considers his “second home” to receive the Ramon Magsaysay Award – Asia’s equivalent of the Nobel Peace Prize – for his relentless work as executive director of Documentation Center of Cambodia.

The center preserves the memory of the genocide in the hopes of transforming horrors into justice.

The man, however, would rather not call it an accomplishment.

“For me, it’s not the achievement. For me, it’s a responsibility. This is my responsibility as a survivor. It’s not about what I should or should not do. It’s a responsibility that I have to do this and I have to do it to the best of my ability. I have to do it honestly because it’s not just for others but also for my family as well,” Chhang told Rappler in an interview on Wednesday, August 29.

Chhang recognizes that in order to move forward, his country has to accept and understand its past. He believes this is powerful means to prevent those who may seek to distort or erase it.

Chhang was only 14 years old when the Khmer Rouge marched into Phnom Penh, forcing him, his family, and millions more to leave the capital in what was the start of a dark chapter in his nation’s history.

A laborer at age 15, he was arrested for picking mushrooms in the rice fields to feed his pregnant sister. He was tortured publicly before villagers.

Then, one of his sisters was accused of stealing rice. In an attempt to prove it, the Khmer Rouge cut open her stomach, eventually leaving her to die.

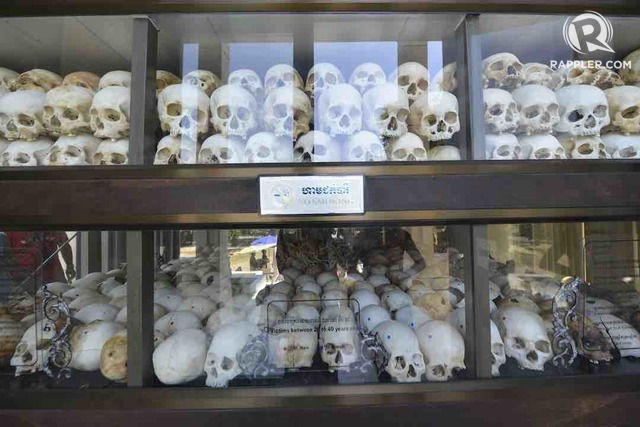

MILLIONS KILLED. From 1975 to 1979, PolPot’s Khmer Rouge killed nearly 2 million Cambodians. These bones were displayed in a memorial at the Killing Fields at Choeung Ek in Phnom Penh. Photo by Jing Magsaysay/Rappler

“It’s a society [where] you can be isolated among your population. And when you become isolated you either become a victim [and] you die or you live as a perpetrator because you have to live, [you have to] steal from someone or point a finger to somebody to save your life. This was how the society that we lived through [during] the Khmer Rouge time,” he said.

To date, he and his family refuse to count the relatives they lost – although it was estimated that there were 60 of them. After all, Chhang said, it is easier to count those who survived, which included him, his now 92-year-old mother, 3 sisters, and a niece.

Turning point

It was not all easy for Chhang to get to where he is now. For a time, he said he was ready to just give up his past and story for a chance at a peaceful nation. After all, after Cambodia suffered under colonization, war, coup d’etat, dictatorship – “you name it,” Chhang said – the people just wanted to move on in peace.

“If that is what the people want, if that is the wish of the people of Cambodia, and I can contribute by giving up my story and history, I would do it. So I did,” he said, recalling the year 1992 when the United Nations assisted the country back to normalization.

But it turned out this was not enough, as the Khmer Rouge continued their violations and atrocities by boycotting the elections, killing people, and refusing to integrate into society. That was when Chhang realized that the country must confront its past to move forward.

“Forgetting is also a crime, you know. When you try to forget, actually it is an act of committing a crime. And you don’t want to become a perpetrator of your own past, of your own history, of your story. So, by confronting it, it perhaps allows you to understand and to bring a closure and move on,” Chhang said.

In 1995, Chhang became the leader of DC-Cam, originally founded as a field office of Yale University’s Cambodian Genocide Program for research, training, and documentation. In 1997, he continued to run it as an independent non-governmental organization.

YOUNG YOUK. This photo dated October 18, 1999 shows Chhang standing in a room where some of the 400,000 documents detailing the gruesome handiwork of the Khmer Rouge exist. File Photo by Philippe Lopez/AFP

His efforts led to the uncovering of over a million documents, half of which served as evidence in the war crime trials; digital mapping of over 23,000 mass graves in Cambodia’s killing fields; the identification of more than 100 prison sites; and interviews with over 10,000 people, both victims and perpetrators. This also helped families get the closure they needed.

Chhang had also successfully pushed for the institutionalization of Khmer Rouge history in Cambodian education. Through his initiative, all grades 7 to 9 students are required to be taught what happened between 1975 and 1979. Colleges, he added, are also required to teach that.

In the desire for truth and justice, it was his investigative and research work that formed part of joint efforts that led to the creation of a UN-backed tribunal, where he also testified as a living witness to genocide. (READ: Top Khmer Rouge leader denies genocide at close of UN-backed trial)

In 2014, a Cambodian court sentenced two former top officials of the Khmer Rouge tolife in prison for committing crimes against humanity.

SECRET PRISON. Tuol Sleng, codenamed S-21, served as a secret prison, where at least 12,000 were killed. Photo by Jing Magsaysay/Rappler

Chhang currently leads DC-Cam’s development of the Sleuk Rith Institute, a permanent hub for genocide studies in Asia based in Phnom Penh.

“And only when you have proper, sufficient documentation of the past, that’s the only way you can begin with the process of justice and then you can discuss about reconciliation and forgiveness,” he said.

“Confronting the past is difficult. Sometimes there’s no answer when you confront it, but it will give you a lesson to prepare yourself for the future,” Chhang said.

Of death threats and facing torturers

It was a difficult task, to say the least, as death threats would fill Chhang’s weeks in the early days of his advocacy work. The Khmer Rouge, though deposed and hidden in the woods, had the means to make sure Chhang would know of their disdain.

But no one and nothing could stop Chhang from documenting the horrors of the past in search of justice for his nation.

“Well, I have death threats almost weekly when I started…. But, you know, if you don’t fight back, you accept you’re a victim for the rest of your life. And why should you continue to be a victim of a crime you never committed? Why should you be afraid of the perpetrators? That’s how you confront history – your own history, own past,” he said.

On top of that was the inevitable harrowing experience of meeting your tormentors, which he did several times in the course of fieldwork.

KILLING TREE. This infamous Killing Tree in Choeung Ek was where Khmer Rouge soldiers would beat children, including infants, until they die. The soldiers would put a loudspeaker nearby so screams of victims won’t be heard. Photo by Camille Elemia/Rappler

He once returned to the village near the Thai border, where he used to live to conduct interviews and verification. By some twist of fate, he and his staff found the 4 prison guards who publicly tortured him.

At some point, it became confusing for Chhang, as he saw the farmers to be truthful and “sincere” in recalling the experience.

“I faced my own perpetrators in the village…. But then I became very upset. Why are they so sincere? I want them to be rude, aggressive. I want them to be monsters. I want them to be arrogant, like who they were then,” he said.

Chhang took the chance to face his past tormentors and asked them if they could remember him. The prison guards said no.

So he asked them again: Do you remember the young boy who was arrested and was tortured in front of the village?

“They got excited because they remembered it, too. They think that by remembering that story they commit acts of collaboraton and [they are] supporting and helping us. But then I told them the boy was me…. The whole room was silent. Nobody talked,” he recalled.

Forgiving the Khmer Rouge, to this day, is difficult, as Chhang said there was never an apology.

“But to forgive, why should I forgive them when they never apologized? Why should I forgive them? Had anyone made an apology? So I think it takes both sides. One must accept the fact that they did wrong to another, then let the other one decide how they would forgive, how they would reconcile the two. But sometimes in Cambodia it is very complex – it’s not about Cambodian killing Cambodian, it’s the fact that they find it difficult to accept. Its very, very [conflicting],” he said.

As for his former torturers, Chhang said they apologized the Cambodian way by offering him food and coconut drink, but he declined it.

“We never met again…so this is perhaps where you would consider forgiveness in this context. Without apology, without saying I will forgive you, I forgive you, we can move on. They move on with their own direction, I move on with my life,” he said.

The need for a ‘national truth’

There would be no justice without truth. But Chhang admits even this could become tricky on a personal level. That is why, he said, there is a need for the government to explain the truth and make sense of it for individuals – precisely what DC-Cam is aiming for.

“If you know the truth, that is justice. You must know the truth. And the truth also is very broad, a bit philosophical. And [it depends on] each of you. There’s a truth for nation, there’s a truth on a personal level,” Chhang said.

“You seem in my family, we see truths in different ways. That is personal…and without the national recognition of the mistake of the past, it’s difficult also to define the meaning of it…. The government has to explain…. So it has to be collaborative national approach, as well as individual approach,” he said.

In fact, he, his mother, and his niece have different ways of dealing with what happened to them and their family.

His niece, who was just 6 when her mother was killed, is now based in the United States. She has never returned to Cambodia in the past 4 decades. For her, nothing could ever make sense of the brutal murder of her mother.

Chhang’s mother found refuge in Buddhist teachings in dealing with the deaths, especially of her daughter.

“For my mother, the truth is, by Buddhist belief, perhaps in the previous life my sister did wrong things to others and now she had to pay back. And she would use the Buddhist teaching as a way to move on and hope that in the next life [my sister] would be born more prosperous and have a good life,” Chhang said.

For him, his way forward is to go back to the past through research and documentation, in the desire to bring justice. And, surely, he has made huge steps in that direction not just for himself but for his fellowmen.

As for the Philippines, Chhang has only well wishes for the country he calls his second home.

SECOND HOME. The Philippine Embassy in Phnom Penh hails Chhang, former refugee in the Philippines, for getting a Ramon Magsaysay Award in 2018. Photo by DFA

Having witnessed the 1986 People Power Revolution that toppled the Marcos dictatorship, the Cambodian human rights leader hopes the country looks back to its past to avoid making the same mistakes.

He said that while he saw “a lot of progress, development” in his visit to the Philippines, he hopes it would not revert to its state before the transition to democracy.

“I regard the Philippines as second home, and I don’t want the Philippines to return to what it used to be. And I hope that the lesson of the past will be incorporated into formal education [for] young Filipinos to learn so they can build a better society,” Chhang said. – Rappler.com